Zhao Shukai: where Ezra Vogel got it wrong

Correcting the misreadings of Deng Xiaoping and his reforms.

Zhao Shukai (赵树凯; b. 1959) is a Chinese official of rural policy and governance. From 1982 to 1989, he worked at the Rural Policy Research Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee’s Secretariat (later reorganised as the State Council’s Rural Development Research Centre and subsequently the Research Centre of Rural Economy under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs). Starting in 1990, he served at the Development Research Centre of the State Council, China’s government cabinet, holding roles including Director General of the Rural Department’s Organisation Research Office and Director General of the Information Centre.

He held short-term visiting positions at the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW), The Australian National University (ANU) (1996–1997); Universities Service Centre for China Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) (1998); Asian/Pacific Studies Institute (APSI), Duke University (2000–2001); Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University (2001–2002); Harvard-Yenching Institute, Harvard University (2010–2011; 2016-2017); and the University of Tübingen, Germany (2012–2013). He also completed an executive education programme in public management at Harvard Kennedy School (2003; 2008) and an executive education programme at Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge (2007).

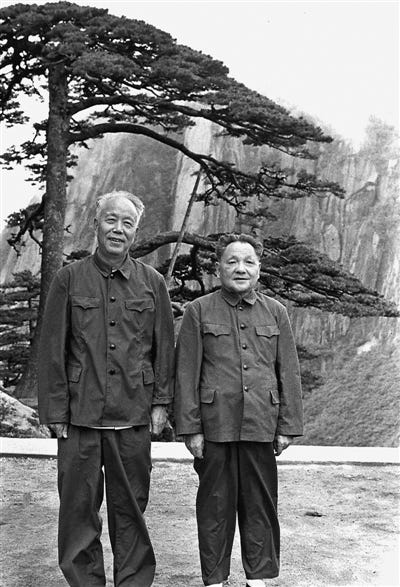

During his visiting positions at Harvard between 2001 and 2017, Zhao met frequently with the late Ezra Vogel to discuss the history of Chinese rural reform. When Vogel was writing Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, Zhao explained relevant chapters of the Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping to him and introduced the basic processes and key events of rural reform. The two also met several times in Beijing.

Zhao has written elsewhere in praise of the high standards that defined Vogel’s scholarly life. Yet, as he notes, “praise is no substitute for criticism; indeed, it is rigorous criticism that gives praise its real weight.” Across two recent WeChat blogs, Zhao Shukai delivers a sharp review of Vogel’s famous book. While Vogel is widely credited with introducing the West to the “Architect of Reform,” Zhao argues that the Harvard professor’s narrative is perhaps a little too tidy. In his view, Vogel’s “misreadings” include: a mistaken turning point, a muddled timeline, an oversimplification of reform twists, and an over-focus on the “Great Man” at the expense of other critical figures.

In the end, Zhao delivers a poignant reminder that less than 50 years after the rural reforms of the 1970s, many narratives have already become obscured. Fact and fiction are increasingly entangled, and errors are being cited as truth. It is a historical responsibility to break out of this historiographical predicament.

—Yuxuan Jia

“Ezra Vogel’s ‘Misreading’” was first published in Zhongguo Nongzheng (Supplement to Series I), a book-form serial publication sponsored by the Shandong University Center for the Study of Policy Making and published by the Research Press. It was later reposted on 21 November 2025 on Zhao’s personal WeChat blog, Guhe Hushan 沽河虎山. “Why Did Ezra Vogel ‘Misread’?” appeared on the same WeChat blog on 22 November 2025.

Zhao has kindly authorised the translation.

赵树凯:傅高义的“误读”

——《邓小平时代·第15章》阅读笔记

Zhao Shukai: Ezra Vogel’s “Misreading”

Reading Notes on Chapter 15 of Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China

Since the publication of Ezra Vogel’s Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, the book has had a wide impact in China and abroad and has been frequently cited in academic studies of China’s reform. The book consists of 24 chapters. Rural reform is discussed in Chapter 15, titled “Economic Readjustment and Rural Reform,” which is divided into four sections: “Builders versus Balancers,” “Wan Li and Rural Reform,” “Township and Village Enterprises,” and “Individual Household Enterprises.”

I have read and compared three editions: the English edition published by Harvard University Press in 2011, the Chinese edition published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press in 2012, and the Chinese edition published by Beijing SDX Joint Publishing Company in 2013.

In my view, the book’s discussion of rural reform captures the main contours of the story, presenting them concisely and engagingly. However, it also contains some “misreadings” that warrant examination and correction, especially when considered as a work on China’s reform history.

Here, the term “misreadings” does not refer to differences in opinion or evaluation. It refers specifically to shortcomings in the presentation of facts, including both mistakes and omissions. These misreadings fall roughly into three areas: gaps in the policy context, distortions in the narrative structure, and inaccuracies in historical details. This also leads me to think that current research on China’s reform history is at an impasse and needs a breakthrough.

I. Gaps in the Policy Context

Reform is first manifested in policy changes, and the history of reform is a history of policy evolution. Vogel’s book sets out to trace the policy process of China’s rural reform and clearly identifies two main policy lines: the household production system and hired labour, which gives the discussion a clear and structured framework. However, there are obvious gaps in the way the policy context is presented.

1. On the Policy of Household Production

Household production was the core issue of China’s rural reform. Its policy process went through three stages: a complete ban, limited permission (for particularly poor rural areas), and full permission (with farmers free to choose). However, this book mistakenly condenses these three stages into two, and it also gets wrong what was primary and what was secondary in identifying the policy turning points.

“In the summer of 1980 Wan Li began to prepare the formal document supporting the new policy, which was to be issued in late September.”1 Here, the September document (i.e., No. 75 Central Document) is mistakenly considered the “formal document” supporting the policy of household production, which is a significant misreading of the reform process.

This document still regarded household production as a form of capitalism and continued to affirm the people’s commune system. It allowed the policy to be implemented “in remote mountainous areas and backward regions,” but stipulated that it should not be carried out in other areas.

The truly “formal document supporting the new policy” is the January 1982 No. 1 Central Document [the first policy document released each year], which announced that household production and contract production “are both production responsibility systems under the socialist collective economy”2, allowing farmers to choose freely. In line with this misreading, the book states that “the transition to household production was completed in 1981.”3 In fact, the policy transition to household production was not completed in 1981, but only after the issuance of No. 1 Central Document in January 1982.

The book devotes considerable space to Deng Xiaoping’s May 1980 talk and places undue emphasis on the policy consequences of this talk. There is no question that the talk offered important political backing for household production and marked a key turning point in the course of rural reform. Even so, its policy position remained anchored in the people’s commune system, and, given the historical conditions of the time, its impact on policy was limited. Deng said:

“Some comrades are worried that this practice may have an adverse effect on the collective economy. I think their fears are unwarranted. Development of the collective economy continues to be our general objective. Where farm output quotas are fixed by household, the production teams still constitute the main economic units.”4

The phrase “the production teams still constitute the main economic units” was used to argue that there was no need to worry about household production, and to justify it within the framework of the people’s commune system. In practice, however, household production fundamentally negates the production-team-based collective economy. Subsequent developments confirmed this as well: household production quickly accelerated the disintegration of that collective structure.

Looking back at the policy debates at the time, it is clear that the speech left ample room for two opposing policy paths. In its wake, critics of household production continued to attack it, questioning its nature and direction, leaving the policy politically on the back foot. Wan Li later reflected on the speech’s limited effect: “Things improved afterwards, but there was still a lot of noise, and the nationwide debate never stopped. Some of the opponents held power, and if they disagreed, you couldn’t get things done.”5

The real breakthrough came with the January 1982 No. 1 Central Document, which signalled a fundamental shift propelled by grassroots practices that had become impossible to contain. Between the 1980 No. 75 Central Document and the 1982 No. 1 Central Document, household production went through another round of intense policy debate, during which Deng Xiaoping made no further public statements on the issue.

2. On the Policy of Private Hiring of Hired Labour

Whether to permit private hiring of labour became the next major policy flashpoint after household production. The dispute began in the countryside but soon spilt well beyond rural areas. It unfolded through a more complex process, carried wider and deeper consequences, and continued throughout the 1980s.

The book’s section on “Individual Household Enterprises” treats this issue as its central thread, and it does capture an important hinge point in the policy process. However, it cites only one Deng Xiaoping remark on hired labour, made in 1983: “let it continue for a couple years, then see how it’s working.”6 It then concludes: “At the 13th Party Congress in 1987, party officials officially permitted individual household enterprises to hire more than seven employees. Deng had scored another victory by using his basic approach to reform: Don’t argue; try it. If it works, let it spread.”7

In reality, the debate over hired-labour policy was far more intricate. After the 1983 remark, Deng made another significant statement in 1985, and the policy retreated after 1989.

During the drafting of the No. 1 Central Document of 1984, on December 9, 1983, Deng Xiaoping asked his secretary to call Hu Qili, then a secretary of the Secretariat of the Central Committee, to convey his view: “Let it take its course. Revisit the matter in two years.”8

After that “two-year wait”, the question of hired-labour policy resurfaced. On 24 November 1985, in a conversation with Bo Yibo, Deng heard about three different situations involving hired labour and concluded: “It is time to apply some control. They are using state resources and state loans, and it will not do if we do not exercise control. In the future it still needs to be guided towards the collective economy, and ultimately it should be guided towards the collective economy.”9

As for what “control” should look like, the conversation suggested imposing progressive income tax rates of 80 or 90 per cent on some businesses that employed hired labour, and differentiating lending policies. When the drafting group tried to incorporate the spirit of Deng’s remarks into the document, internal debate was fierce, and no consensus could be reached. In the end, Du Runsheng said, “The document should avoid the issue of hired labour, because it cannot be made clear in one or two sentences.”10 As a result, the instruction to “apply some control” never made it into the text.

After the 1986 No. 1 Central Document was issued, the Rural Policy Research Office of the Central Committee Secretariat and other departments organised a series of special studies on hired labour, but they struggled to devise workable restrictive measures. By late 1986, when Du Runsheng led the drafting of the 1987 rural work document, the issue was still being sidestepped.

Although no central document had been issued to restrict the use of hired labour, internal policy debate continued. In May 1986, a senior official told Du Runsheng, “First, they must pay taxes. Second, the number of employees should be limited to some extent. Comrade Runsheng does not favour limits. I favour limits, but I cannot say exactly how. The employer’s pay should not exceed workers’ pay by more than a certain multiple.”11

As circumstances shifted, a restrictive policy emerged three years later. In August 1989, the CPC Central Committee issued a Notice on Strengthening Party Building, which stipulated that Party members were not allowed to employ hired labour: “Our Party is the vanguard of the working class. There is a de facto relationship of exploitation between private entrepreneurs and workers, and private entrepreneurs cannot be admitted to the Party.”12

All this suggests Vogel’s narrative on hired-labour policy is overly neat and one-sided, failing to capture a protracted, contested process marked by reversals and unresolved tensions.

3. On the “Agricultural Consolidation” of 1975

The book devotes substantial space to Deng Xiaoping’s “overall consolidation” in 1975, yet it does not mention “agricultural consolidation.” At the 1975 National Conference on Learning from Dazhai in Agriculture, Deng stated: “Industry needs consolidation, agriculture needs consolidation, commerce needs consolidation, our culture and education also need consolidation, and our science and technology teams need consolidation. As for literature and art, Chairman Mao called it adjustment, but in fact adjustment is also a kind of consolidation.”13 Following his return to office, Deng delivered two important speeches on rural policy.

On the morning of 15 September, at the opening ceremony of the National Conference on Learning from Dazhai in Agriculture, Deng Xiaoping focused on agricultural consolidation:

“Capitalist tendencies in the countryside already exist to a considerable extent, and in some regions and in some respects they have developed further. There is a two-line struggle in the countryside, and this calls for consolidation. In the past the policy package known as the ‘Three Autonomies and One Contract’ [which granted autonomy in three areas, namely private plots, free markets, and self-responsibility for profits and losses, together with the household contract responsibility system] had been criticised. Some comrades now say that in the countryside, there is not only ‘Three Autonomies and One Contract’ but also ‘Three Autonomies and One Division,’ meaning collective land is being divided for individual household farming. This phenomenon should alert the entire Party. If agriculture is to advance, it will not work unless this phenomenon is corrected and the collective economy is consolidated and developed. No! That would be a step backwards, not forward.”14

Deng also said: “After the people’s commune system was introduced, Chairman Mao summed up its characteristics as ‘large in scale and collective in ownership.’ The people’s commune system is certainly a successful system.”

At the same time, Deng endorsed Dazhai’s evaluation system by assigning work points:

“When learning from Dazhai, do not look only at grain output. Study some of the specific policies in Dazhai and Xiyang [the county where Dazhai is located]. The evaluation system by assigning work points, for example, is a policy issue and should not be seen merely as a question of method. In Dazhai, there is one evaluation each year. Please study this. In my view, this is not a simple technical issue but a matter of political line. It helps to cultivate revolutionary consciousness and greatly strengthens people’s drive.”

On the morning of 27 September, at a rural work symposium convened by the Central Committee, Deng Xiaoping made another important statement on rural policy. The forum was called after Vice Premier Chen Yonggui wrote to Mao Zedong in August, recommending that agriculture should “go all out for rapid growth” and that brigade-level accounting be introduced as a matter of urgency.15 Acting on Mao’s instructions, the Central Committee convened the meeting.

The central issue in the debate was whether the basic accounting unit should be shifted from the production team to the production brigade. Vice Premiers Ji Dengkui and Hua Guofeng, along with provincial Party secretaries including Zhao Ziyang of Sichuan and Tan Qilong of Zhejiang, argued that the conditions for such a shift were not yet ripe. On the morning of 27 September, Deng said at the meeting: “The guiding ideology must consciously steer in this direction and move forward in this direction. This is very important. In the future, we must gradually move to commune ownership and truly realise ‘large in scale and collective in ownership.’”16

Taken together, these two speeches suggest that “agricultural consolidation” was pointing in a different direction from the other consolidation efforts. Researchers examining Deng Xiaoping’s role in rural reform and the evolution of policy from the Cultural Revolution to the reform era should pay close attention to this.

II. Distortions in the Narrative Structure

In outlining the broad trajectory of rural reform, Vogel’s book captures the main storylines. It highlights Anhui’s leading role, as well as the driving roles played by Deng Xiaoping and Wan Li. What it lacks, however, is sustained attention to Sichuan’s reforms and to Hu Yaobang’s role. The result is a distorted narrative structure.

1. On Rural Reform in Sichuan

The book mentions Sichuan only once. It notes that on 1 February 1978, Deng Xiaoping “told Sichuan Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang about Wan Li’s success in Anhui with the six-point proposal” and that “Deng encouraged Zhao to allow bold experiments similar to those of Wan Li, and Zhao complied, quickly developing a twelve-point program for decentralizing responsibility for agricultural production.”17 This framing leaves the impression that Sichuan moved ahead only because Deng encouraged it, and only by following Anhui’s lead. That was not the case.

Zhao Ziyang became Sichuan’s top leader in the autumn of 1975. In early 1977, he began a series of agricultural policy adjustments, including changes to cropping systems, encouragement of household sideline production, expansion of private plots, smaller production teams, and encouragement of production-team contracting.

Sichuan’s distinctive move was to exploit the policy latitude within the Regulations on the Work of Rural People’s Communes and to become the first in the country to correct rural policies associated with the “Dazhai experience”, which had pushed “left” policies to an even more radical extreme.

By “more radical”, the point is this: the Regulations on the Work of Rural People’s Communes already set out a comprehensive “left” policy framework, but still left farmers some limited room for autonomy, such as private plots, market trading, poultry raising, and household sidelines. The “Dazhai experience” removed even that narrow space. Sichuan’s adjustments began to show results after the autumn of 1977 and delivered major gains after the autumn of 1978.

Comparing Sichuan and Anhui, Sichuan began adjusting policy earlier and did so in relatively moderate ways, while Anhui moved faster and adopted more radical measures. By early 1979, the two provinces had taken different positions on household production. The Anhui provincial Party committee officially agreed to run “experiments” in Shannan Commune, Feixi County, whereas the Sichuan provincial Party committee opted for tacit acceptance.

On 9 January 1979, at an enlarged meeting of the standing committee of the Sichuan provincial Party committee, Zhao Ziyang said: “We should educate cadres not to ‘correct’ certain practices simply because they regard them as questions of political line. This is a matter of understanding, and people should be allowed to experiment a little.” He added, “What was originally an economic issue has been turned into a political campaign. When the Regulations on the People’s Commune were revised, it was made clear that if the masses agreed on other methods, those methods could also be used. We should sum up experience through practice; do not arbitrarily elevate the issue into a question of political line.”18

On 6 February, at a meeting of the standing committee of the Anhui provincial Party committee, Wan Li said: “Some of the things criticised in the past may have been right, and some may have been wrong. They must be tested in practice.” He then explicitly proposed experiments in household production: “I propose carrying out household production experiments in Shannan Commune. If, as some people worry, this leads down the capitalist road, I do not think there is anything to be afraid of. It can be pulled back. If output falls and grain cannot be collected, some grain can be transferred to them.”19

Anhui’s policy adjustments produced major results after the autumn of 1979. After a year of experimentation, in January 1980, the Anhui provincial Party committee endorsed household production as “one form of the responsibility system”, giving it formal status.20 Anhui became the first province in the country where the provincial leadership clearly backed household production.

Vogel’s book also overlooks another major Sichuan contribution to rural reform: it was the first province to begin dismantling the people’s communes. From the autumn of 1979, Zhao Ziyang led pilot reforms of the commune system in Guanghan County, later extending them to Xindu and Qionglai. The core of these pilots was to replace the “integration of government and commune” with a separation of Party and government and of government and enterprise.

In September 1980, Xiangyang Township in Guanghan County officially put up the signboard of a “Township People’s Government”, becoming the first case in China of abolishing a people’s commune.21 This Sichuan breakthrough was not merely an adjustment to rural policy; it was also the earliest step towards rebuilding primary state institutions. Vogel’s book does not mention it—whether because the author was unaware of it or because he chose to avoid it. Either way, something important is missing.

Another notable Sichuan contribution to rural reform came after Zhao Ziyang returned from a visit to Yugoslavia in August 1978. He “proposed to Hua Guofeng that integrated agriculture–industry–commerce reforms be tried in Qionglai, Guanghan, and Xindu counties and the Zoigê Pasture in Sichuan Province, with the provincial Party committee given full responsibility and relevant departments of the State Council not allowed to intervene. Hua Guofeng agreed.”22

These so-called “agriculture–industry–commerce complexes”, or integrated agriculture–industry–commerce arrangements, followed a logic akin to what later became known in the 1990s as “agricultural industrialisation”. The core idea was to move beyond a model in which agriculture and rural areas served only as suppliers of raw materials to industry and cities, and instead enable farmers to share in the gains from processing and circulation. This initiative had a major influence on rural industrialisation and the rise of township and village enterprises.

2. On Hu Yaobang and Rural Reform

On Hu Yaobang, Chapter 15 “Economic Readjustment and Rural Reform, 1978–1982” notes: “In early 1980, Wan Li, seeking Hu Yaobang’s support, told Hu that it wouldn’t work to have people at lower levels surreptitiously practising contracting down to the household: instead they needed the full support of the top Party leaders. Wan Li thus suggested to Hu Yaobang that they convene a meeting of provincial party secretaries to give clear public support for the policy.”23

There is nothing wrong with the passage in itself. The problem is that it is the only point in the chapter where Hu Yaobang is mentioned in connection with rural reform. The mention is plainly cursory and the perspective somewhat skewed, leaving Hu without the place he merits in the story.

In its narrative of rural reform, the title of Chapter 15 suggests that the focus is “1978–1982.” In my view, any sketch of Hu Yaobang’s contributions during these years must not overlook several key aspects.

In early 1978, before his tenure as General Secretary to the Party Chairman, Hu delivered a scathing critique at the Central Party School regarding the “Learn from Dazhai” campaign and its obsession with constructing man-made plains. He denounced these projects as “ecologically destructive, a drain on the people’s toil and treasure, and ultimately more trouble than they were worth.” His remarks sent shockwaves through the upper echelons of power and reportedly left Vice Premier Chen Yonggui “furious.”24

By early 1979, shortly after becoming the General Secretary to the Party Chairman, Hu presided over the drafting of a central document that removed the “class labels” from those designated as landlords or rich peasants. Even though the State Agricultural Commission’s official response at the time was entirely unsupportive25, the document was issued with remarkable speed. In the context of rural work, this move cut the ground out from under the old orthodoxy of “class struggle as the key link 以阶级斗争为纲.”

After assuming the role of General Secretary, Hu Yaobang addressed a meeting of the Propaganda Department in July 1980:

“The Central Committee does not oppose household production. Household production should not be confused with individual farming—and even where individual farming exists, it must not be reflexively equated with capitalism. To suggest that working individually is synonymous with taking the capitalist road is theoretically wrong.”

“There is a second misunderstanding on this issue, that is to conflate the mode of labour—collective or separate, as a team or as an individual—with the system of ownership, and to believe that socialism naturally requires collective, grouped labour at all times; that if labour is dispersed and a person works alone, then it is taking the capitalist road. In fact, these are two entirely different things.”

“Under the regressive systems of serfdom, labour was often collective, not individual.”26

In clear and concise language, Hu Yaobang explained that household production was, in itself, unrelated to the distinction between capitalism and socialism. Among the statements made by the top leadership on the matter at the time, his was the most theoretically thorough.

In October 1980, shortly after the release of Central Document No. 75, Hu chaired a meeting of the Central Committee Secretariat that adopted Central Document No. 83 [which forwarded Shanxi’s “Inspection Report on the Lessons and Experience of the ‘Learn from Dazhai in Agriculture’ Movement” and appended a lengthy editorial note]. In effect, this was a fundamental political reckoning with the “Learn from Dazhai” campaign, clearing a major obstacle to rural reform.

By early 1981, Hu had proposed and pressed the State Agricultural Commission to undertake a rethink of multiple policies. This effort culminated in Central Document No. 13 [which forwarded Du Runsheng’s “Some Views on Issues in Rural Economic Policy”] and helped correct the radical “Grain First 以粮为纲” line that had prevailed for decades. He also took the lead in challenging entrenched policy taboos, openly supporting farmers’ right to purchase large means of production such as tractors and to engage in long-distance trade, thereby bringing the peasantry into market circulation.

In assessing Hu Yaobang’s contribution to rural reform, it is also important to consider the series of rural policy documents issued between 1982 and 1987. In July 1981, Hu Yaobang gave a clear written instruction to draft a new central document27, which paved the way for the 1982 No. 1 Central Document. This document, once issued, proved highly effective, and Hu Yaobang instructed that, from then on, each year’s No. 1 Central Document should focus on rural work.

From 1982 onward, Hu Yaobang chaired the key discussions, revisions, and approval procedures of six successive drafts of central documents on rural reforms. After five consecutive No. 1 Central Documents, the 1987 rural policy document was also originally intended to be issued as the No. 1 Central Document. The draft had largely completed review and revision at the Central Committee Secretariat chaired by Hu, but after his resignation, the numbering sequence was changed, and it was issued instead as Central Document No. 528.

In the 1980s, the process for formulating central documents differed sharply from later decision-making procedures. Back then, the Central Committee Secretariat took the lead in commissioning drafts and in discussing and revising them. Once a document had been approved by the Secretariat, it would be circulated to Politburo members for sign-off and generally did not go to a formal Politburo meeting. Of the five No. 1 Central Documents, only the 1983 document was discussed at a Politburo meeting.

Hu Yaobang’s central role in rural reform was reflected not only in his chairing Secretariat or Politburo meetings to review and approve documents, but also in his direct involvement in identifying policy priorities, setting the agenda, organising policy research, and overseeing drafting. On a number of major issues, he was the first to speak out, break through ideological taboos, advance new policy ideas, and take political risks to push reform forward.

In the difficult process of securing breakthroughs in rural reform, Hu Yaobang was Wan Li’s ally and principal backer—a central pillar of the reform effort. In later recollections, Wan Li repeatedly emphasised the importance of Hu’s role.

In Anhui, as provincial Party secretary, Wan Li could take the initiative in setting the agenda. At the centre, however, he was one of eleven secretaries of the Central Committee Secretariat and, before September 1982, was not yet a member of the Politburo, which left him relatively weak in high-level decision-making. Under these circumstances, Hu Yaobang’s leadership and support were crucial.

3. On the Evaluation Of Figures and the Use of Sources

Assessing the roles played by different leaders in rural reform is an unusually complex task. Take Zhao Ziyang and Wan Li. It requires comparing the distinctive features of Sichuan’s and Anhui’s reforms before 1980, tracing the differences of opinion before the release of the 1980 Central Document No. 75 and the 1982 No. 1 Central Document, and reckoning with power struggles at the top echelon that went beyond the policies themselves. Once Hu Yaobang’s and Deng Xiaoping’s roles are added, the narrative becomes even harder to handle.

Vogel’s book follows a clear line of argument, but it has obvious structural gaps, and the weight it assigns to different figures is uneven. During the 2016–2017 academic year, when I was a visiting scholar at Harvard, I discussed these issues with Ezra Vogel several times. In December 2018, in Beijing, we met again and spent an afternoon discussing them. Had he been given a few more years to complete his planned biography of Hu Yaobang, it might well have helped to remedy some of these shortcomings.

In studying the history of reform, leaders’ collected works and chronological records merit close attention and provide a basic foundation for research. At the same time, these curated collections and chronologies have clear limitations.

First, many speeches and articles were never included, leaving significant gaps. For example, Selected Important Documents on Agriculture and Rural Work in a New Period, published by the Central Party Literature Press in 199229, includes one piece by Zhao Ziyang but not a single one by Hu Yaobang.

Selected Works of Hu Yaobang, published by the People’s Publishing House in 2015, contains 77 items in total, yet only two deal with rural issues: “Remarks During an Inspection Visit to the Beijing Suburbs” (April 1980) and “Protecting and Vigorously Developing the Rural Commodity Economy” based on main points of Hu’s speech at a meeting of the Central Committee Secretariat (December 1983). Important as these two speeches are, they fall far short of capturing Hu Yaobang’s pioneering and innovative contribution to rural reform.

Second, many items that do appear in selected works and chronologies have been edited or abridged, which makes it harder to grasp the full picture and can, at times, obscure the central points. Although Selected Works of Wan Li includes a number of pieces on rural reform, it omits his most important speeches from the period when he was a central leader and rural reform was making its decisive breakthroughs. At the time, there were disagreements within the editorial group, of which I was a member: the team deliberately excluded Wan’s sharper criticisms of certain departments and softened some of the more pointed language. As a result, the selected texts can no longer convey the tense atmosphere that surrounded policy disputes.

For research on the history of reform, careful reading of policy documents is especially important. The language of rural policy is a specialised vocabulary system that reflects the historical evolution of rural work since the Party’s founding, and particularly since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Many policy terms are colloquial, yet their concrete policy content and political implications shift from one period to another. Making sense of this policy language and interpreting policy documents requires a firm grasp of the historical and policy context. This poses a real challenge for research on the history of reform.

III. Errors in Historical Details

The importance of detail in historical writing needs no explanation. When reading works of history, my attention often goes first to the details. Any single detail may not seem significant on its own, but the handling of seemingly minor points can reveal a great deal about an author’s command and underlying understanding of the historical context.

1. On Wan Li’s First Arrival in Anhui

“In the first few weeks after his arrival in Anhui in August 1977, Wan Li visited all the major rural areas of the province.”30 The first half of this statement is incorrect, and the second is clearly problematic as well. Wan Li did not arrive in Anhui in August, but in June. Ordinarily, a difference of two months would not matter much, but what was seen as most urgent at the outset of a new posting is closely bound up with political judgement.

The sequence was as follows. After being “suspended for inspection” for nearly a year on the post of Minister of Railways, Wan Li was appointed vice minister of the Ministry of Light Industry in April 1977. In early June, he was appointed second secretary of the Hubei Provincial Party Committee. Before leaving for Hubei, he paid Deng Xiaoping a farewell call, but Deng told him not to go yet. Wan Li was then reassigned and, on 22 June, appointed first secretary of the Anhui Provincial Party Committee, departing Beijing for Anhui the same day31.

When Wan Li first arrived in Anhui, his main efforts went into dismantling networks associated with the “Gang of Four” and dealing with the Cultural Revolution’s Rebel Faction, addressing military personnel working within the Party and government apparatus, and reshaping the provincial and prefectural leadership teams. Only later did his focus shift to agricultural issues.

Wan Li’s move from second secretary of the Hubei Provincial Party Committee to first secretary of the Anhui Provincial Party Committee came about because Deng Xiaoping raised the matter with Hua Guofeng and Ye Jianying32. Deng’s formal return to office took place at the Third Plenary Session of the Tenth Central Committee in mid-July 1977. This personnel change suggests that Deng already had a decisive say in senior appointments more than a month before his return was officially announced, a point with important implications for analysing the high-level power structure of the time.

The book states that “even before Wan Li arrived in Anhui, the party had directed its Rural Policy Research Office to survey several counties in Anhui’s Chu prefecture.”33 It provides neither a quotation nor a note for this claim, making the source difficult to trace. The problem is that, at the time, there was no Rural Policy Research Office at the central level [it was established in 1982], nor a State Council Rural Development Research Centre [the China Rural Development Research Centre was established in 1985, renamed the State Council Rural Development Research Centre in 1987, and ultimately abolished in 1989].

In 1977, the central body responsible for rural work was the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Under the leadership’s internal division of responsibilities, the ministry functioned both as the Party’s rural-work department and as the State Council’s administrative agency in charge of agriculture, with no separate rural policy research institution. The source invoked here is clearly mistaken.

2. Personnel Changes among Agricultural Leaders

“Although Chen Yonggui was replaced as vice premier in charge of agriculture shortly after the Third Plenum, his replacement Wang Renzhong still supported the Dazhai model.”34 As vice premiers of the State Council, Chen Yonggui and Wang Renzhong were not, in fact, predecessors and successors—either chronologically or in terms of portfolio. Wang Renzhong took charge of agriculture not as Chen Yonggui’s successor, but as Ji Dengkui’s.

Although Chen Yonggui served as vice premier for more than four years, from February 1975 to September 1980, and appeared frequently at high-level events, he was not, in a substantive sense, in charge of agriculture. From the latter half of 1969 onward, the central leaders in charge of agriculture were first Ji Dengkui and then Hua Guofeng. After Hua became acting premier, Ji Dengkui again handled agricultural affairs. From the second half of 1973, Chen began to participate in high-level rural work and to put forward policy views, but, broadly speaking, within the central rural work leadership structure, he served more as a political symbol—his presence was largely symbolic.

In 1978, Ji Dengkui oversaw the drafting of two agricultural documents for the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee and presented them at the meeting. During the drafting process, Chen Yonggui sometimes participated in discussions and occasionally offered comments. The central leadership structure for rural work during the Cultural Revolution was more complex than either before the Cultural Revolution or after the start of reform, and it is not possible to explore it in detail here.

In addition, the rule-by-terror tactics and falsification associated with the “Dazhai experience” had already been exposed at high levels in the autumn of 1978 and were further brought to light in the spring of 1979. After Wang Renzhong became vice premier in early 1979, the top leadership no longer stressed “learning from Dazhai in agriculture.” It is therefore inaccurate to say that “Wang Renzhong still supported the Dazhai model.”

The book states that “At the Fifth Plenum of the 11th Party Congress in early 1980…Wan Li became a vice premier, director of the State Agricultural Commission, and the member of the party Secretariat in charge of agriculture.”35 This account of the personnel changes is inaccurate. Wan Li did not assume these three posts simultaneously, because each required a different appointment procedure.

At the Fifth Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee in February 1980, Wan Li became a secretary of the Central Committee Secretariat. At the fourteenth meeting of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in April 1980, he was appointed a vice premier of the State Council. In August, he additionally took up the post of director of the State Agricultural Commission.

In practice, Wan Li replaced Wang Renzhong as the leading official in charge of agriculture in March 1980 and went to the State Agricultural Commission on 29 March to receive his first briefing36.

“In August 1980 the leaders opposing contracting down to the household—Hua Guofeng, Chen Yonggui, and Wang Renzhong—were formally relieved of their posts as premier and vice premiers, respectively.”37 This wording suggests that Wang Renzhong and Chen Yonggui lost their vice-premier posts because they opposed household production. That was not the case.

After Wang Renzhong ceased to serve as vice premier, he became a secretary of the Central Committee Secretariat and head of the Central Propaganda Department—positions no less important than vice premier. Nor was Chen Yonggui removed from office because he opposed household production. More broadly, during the rural reforms of the 1980s, leaders at both central and local levels were not demoted for opposing household production; on the contrary, some were promoted and assigned important posts. Du Runsheng discussed this phenomenon explicitly in his later years. A full explanation would require a deeper examination of high-level politics and lies beyond the scope of this article.

3. On Institutional Evolution and a Particular Meeting

Vogel’s book notes that, when drafting Central Document No. 75 in the summer of 1980, “Wan Li called on Du Runsheng, the highly respected agricultural specialist who had been head of the Secretariat of the Rural Work Department and also head of the Rural Development Institute on agriculture policy.”38 This phrasing suggests that Ezra Vogel understood Du Runsheng to have headed the State Agricultural Commission (Secretariat of the Rural Work Department) while simultaneously leading the Rural Policy Research Office of the Central Committee Secretariat (the Rural Development Institute on agriculture policy).

In fact, the State Agricultural Commission was abolished in the spring of 1982, and the Rural Policy Research Office of the Central Committee Secretariat was established thereafter. Du Runsheng first served as deputy director of the State Agricultural Commission; only after it was dissolved did he become director of the newly created Rural Policy Research Office. He therefore did not hold the two posts concurrently.

The book recounts that “At a meeting in Beijing, when a vice minister of agriculture attacked the practice of contracting down to the household, Wan Li shot back: ‘You are a feitou da er’ (fat head and big ears—in other words, like a pig). ‘You have plenty to eat. The peasants are thin because they do not have enough to eat. How can you tell the peasants they can’t find a way to have enough to eat?”39 The note to this passage reads: “Interview with Yao Jianfu, who attended the meeting, April 2009. [Zhang Gensheng, then Vice Minister of Agriculture, attended the meeting; his memoirs preserve a record of Wan Li’s remarks.]”40

[In the original English edition published by Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (2011), the citation relies solely on the interview with Yao Jianfu. However, the translated Chinese editions include this supplementary reference to Zhang Gensheng. —Yuxuan Jia]

Wan Li did sharply criticise a vice minister of agriculture, but this took place at a Party leadership meeting of the Ministry of Agriculture on 1 March 1981, and again at a Party leadership meeting of the State Agricultural Commission on 11 March. Zhang Gensheng had been transferred to Jilin at the end of 1979 and was no longer at the Ministry of Agriculture, so he did not attend these meetings. Yao Jianfu only joined the Rural Policy Research Office of the Central Committee Secretariat in the autumn of 1982 and was not involved at the time, so his account in the interview cannot be accurate. Wan Li’s criticism at the meeting was indeed very sharp, but he did not use the kind of expression quoted in the book.

In my view, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China is a monumental work with impressively broad coverage, but its treatment of rural reform is not especially penetrating. This criticism is made from the standpoint of specialised research on the history of reform, rather than the expectations of a general reader. Read simply as a political biography, the level of scrutiny offered here may seem exacting. The aim, however, is to invite serious scholarly debate and to encourage further research on Chinese reform and politics in the 1980s. Scholarship advances through such exchange, and informed criticism from specialists is part of the process.

I have written elsewhere in praise of the high standards that marked Ezra Vogel’s scholarly life. But praise is no substitute for criticism; indeed, it is rigorous criticism that gives praise its real weight. A scholar of Vogel’s stature deserves deep respect and admiration, but not blind faith or unthinking assent. He is both a model to learn from and an author whose work invites critical engagement.

When reading leading scholars, respect and a willingness to learn should go hand in hand with discernment and a critical eye. Scholarship advances only through this kind of engagement, and earlier generations set a strong example. In his Doubts About Ancient History, Gu Jiegang (1892-1980) praised Records of the Grand Historian, yet also pointedly noted that some parts “have not gone through careful revision; some passages are even rather rough,” and that certain sections are “fabricated pseudo-history devised to gloss over history.”41 Yang Lien-sheng likewise criticised several errors in Joseph Needham’s Introductory Orientations to Science and Civilisation in China, observing that “unfortunately there is already evidence that the author is rather careless with regard to philological matters.”42

That is the scholarly spirit required today. Even a work as brilliant and enduring as Records of the Grand Historian calls for criticism, still the more so other works. What matters is whether criticism rests on solid evidence.

This, in turn, brings to mind the state of research on China’s rural reform in recent years. On the surface, the field looks busy and productive, yet major breakthroughs have been few. Many publications are not grounded in rigorous scholarship, but start from propaganda and praise, seeking favour with those in power rather than pursuing the truth. Even where the work is earnest, it often amounts to little more than polishing minor details: the craftsmanship may be impressive, but the substantive contribution is limited.

Less than half a century has passed since rural reform began in the late 1970s. That is not a long span of time, yet many narratives have already become hard to verify, fact and fiction are mixed up, and errors keep cropping up. If scholars today do not make a sustained effort to investigate the record and separate the true from the false, later generations will inevitably pay the price. Breaking out of this predicament is a historical responsibility that rests with researchers now.

赵树凯:傅高义何以“误读”?

Zhao Shukai: Why Did Ezra Vogel “Misread”?

I once wrote an article titled “Ezra Vogel’s ‘Misreadings’,” in which I pointed out several factual errors in the sections on rural reform in Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China. The purpose was not to pick a fight with Vogel. If there was a target at all, it was the excessive praise that had been lavished on his work. Unless this habit of uncritical congratulation is broken, talk of “academic development” will remain hollow.

In “Ezra Vogel’s ‘Misreadings’,” I grouped the problems into three areas. First, there is a misreading of the basic trajectory of rural reform, most clearly seen in the serious overstatement of the significance of Deng Xiaoping’s May 1980 talk, and the complete neglect of the 1982 No. 1 Central Document as the fundamental policy turning point. The account of how policy on hired labour evolved is also seriously flawed, completely overlooking the fact that Deng at one point called for strict limits on hired labour.

Second, the narrative structure is skewed in a way that leaves the policy process incomplete, and it significantly understates the roles of Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang.

Third, the book contains a number of factual errors which, while minor in isolation, point to a weaker grasp of the political context of reform—for example, the claim that Wan Li succeeded Chen Yonggui as the vice premier responsible for agriculture, as well as various misunderstandings about the central rural work institutions.

The shortcomings in Ezra Vogel’s book may have many causes, but, in my view, they can be traced to three main issues from a methodological standpoint.

I. Live by the Interview, Die by the Interview

Ezra Vogel enjoyed unusually favourable conditions for conducting interviews. He was able to speak with leading figures in politics, academia, and business, and the range and seniority of his interviewees were far beyond the reach of Chinese scholars. The problem, however, is that many of those he spoke to were more inclined to offer praise than to pursue the truth or speak frankly. The interviewees were a selected group, and the bias in their accounts was hard to miss. In other words, although Vogel carried out a large number of interviews across multiple levels, his pool of interviewees lacked diversity, and alternative voices were largely absent.

At the same time, Vogel did not do enough to develop a systematic grasp of his interview material or to subject it to detailed analysis. Any interview-based research faces similar problems: interviewees may misremember, their knowledge is partial, and they bring their own biases and preferences. Different people can give different accounts of the same event, and even the same person may recount it differently on different occasions. For that reason, oral testimony is rarely firm evidence on its own and requires careful vetting—above all by cross-checking it against documentary sources. Vogel’s interviews were no exception. The errors in the book suggest that he leaned too heavily on interview material and did not spend enough effort corroborating and assessing it against other sources.

II. Rich in Interviews, Poor in Documentary Sources

In his use of Chinese-language documentary materials, Ezra Vogel showed a bias in source selection. The main issue is that he did not fully draw on the sources richest in detail and closest to the actual course of reform.

On Wan Li and rural reform, for example, the main work he appears to have consulted was Liu Changgen’s Wan Li in Anhui [Liu Changgen and Ji Fei, Wan Li zai Anhui (Wan Li in Anhui) (Hong Kong: Kaiyichubanshe, 2001], a relatively thin book, while more detailed and informative studies, such as Zhang Guangyou’s Fengyun Wanli (Wan Li in turbulent times) received little attention. The author of the former is a writer; the latter followed Wan Li throughout the rural reform process in Anhui. Vogel’s research clearly overlooked Zhang Guangyou’s writings.

In the historiography of China’s rural reform, there are only a handful of books of this kind. With more careful documentary work, systematically comparing the available accounts and selecting sources with greater rigour, many issues are not difficult to clarify. It is clear that Vogel’s use of Chinese-language sources shows significant shortcomings.

For research on contemporary China, including the history of rural reform, Harvard has exceptionally rich Chinese-language holdings, notably the collections of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and the Harvard-Yenching Library. The Harvard-Yenching Library, in particular, has not only an enormous print collection but has, in recent years, also added complete sets of electronic materials closely related to rural reform, including a range of internal documents—some of them originally classified.

Over the past two decades, I have made many research visits to Harvard. As a collaborator of Professor Elizabeth J. Perry, then director of the Fairbank Center and president of the Harvard-Yenching Institute, I was granted special access to these collections and became closely familiar with Harvard’s holdings on contemporary China. All of the errors and shortcomings I have identified in Vogel’s work could be checked and resolved using the Chinese-language materials currently available at Harvard. In other words, had Vogel made fuller use of these holdings, the major errors in his book could have been avoided.

III. Strong in Speaking, Weak in Reading

Although many people have praised Ezra Vogel’s Chinese skills and admired the persistence with which he continued studying the language in his later years, in my view, a significant source of the book’s shortcomings lies in the limits of his Chinese reading ability.

My discussions with Vogel about China’s rural reform took place mainly in the 2001–2002 academic year, when I was a visiting scholar at the Fairbank Center, and he was working on Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China. On many occasions, I went to his home to walk him through relevant passages in the Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping and to outline the basic trajectory and key events of rural reform. Later, in the spring and summer of 2003, 2008, and 2011, while attending senior executive programmes in public administration at Harvard Kennedy School, and again during visiting appointments at the Harvard-Yenching Institute in 2010–2011 and 2016–2017, I had further opportunities to meet with him and continue these discussions. We also discussed several times when Vogel visited Beijing.

When we read the Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping together, he would usually flag key passages and ask Harvard doctoral students, who were his research assistants, to translate them into English. The translations were written on slips of paper and tucked into the volumes for later reference while he was writing. At the time, two or three graduate students were doing this work for him.

In Harvard’s China studies field at the time, the two most senior professors were Ezra Vogel and Roderick MacFarquhar. From personal conversations with both, I found that their Chinese had different strengths: Vogel was stronger in speaking than in reading, while MacFarquhar was stronger in reading than in speaking.

My conversations with Vogel were conducted mainly in Chinese. My conversations with MacFarquhar initially took place in English, but because my English—especially spoken English—was weak, communication was difficult. Over time, a workable method emerged: I spoke Chinese and MacFarquhar spoke English. He listened in Chinese, and I listened in English, and the exchange became much smoother. When something was unclear, he would often pull a book from the shelf so that we could look at it together. The arrangement was a bit odd, but highly effective.

Comparing their Chinese, my impression is that their listening ability was broadly similar, perhaps with a slight edge for Vogel. In spoken Chinese, Vogel was clearly stronger than MacFarquhar; in reading, MacFarquhar was clearly stronger than Vogel.

This article has focused mainly on shortcomings in Vogel’s research methods. As for choices he may have made deliberately for reasons of his own, I will not speculate here.

Ezra F. Vogel, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011), 441 (hereafter Vogel, Deng Xiaoping).

Party Literature Research Office of the CPC Central Committee and Development Research Center of the State Council, eds., Xin shiqi nongye he nongcun gongzuo zhongyao wenxian xuanbian [Selected Important Documents on Agricultural and Rural Work in the New Period], 1st ed. (Beijing: Central Party Literature Press, October 1992), 117.

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 445

Deng Xiaoping, Deng Xiaoping wenxuan [Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping], vol. 2, 2nd ed. (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, October 1994), 315.

Wan Li, “Nongcun gaige shi zenme gao qilai de” [How Rural Reform Was Carried Out], in Ouyang Song, ed., Gaige kaifang koushu shi [Oral History of China’s Reform and Opening Up] (Beijing: China Renmin University Press, January 2014), 19.

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 449

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 449

Party Literature Research Office of the CPC Central Committee, ed., Deng Xiaoping nianpu [Chronicle of Deng Xiaoping] (Beijing: Central Party Literature Press, 2004), 948.

Ibid., 1047.

Rural Policy Research Office under the Secretariat of the Central Committee, Meeting Materials (December 1985), n.p.

Rural Policy Research Office under the Secretariat of the Central Committee, Meeting Materials (May 1986), n.p.

Party Literature Research Office of the CPC Central Committee, ed., Shisanda yilai zhongyao wenxian xuanbian [Selected Important Documents since the Thirteenth National Congress of the CPC], 1st ed. (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, October 1991), 597.

National Conference on Learning from Dazhai in Agriculture, Conference Materials (September 1975), n.p.

Ibid.

Party Literature Research Office of the CPC Central Committee, ed., Mao Zedong nianpu [Chronicle of Mao Zedong], vol. 6 (Beijing: Central Party Literature Press, December 2013), 606.

National Conference on Learning from Dazhai in Agriculture, Conference Materials (September 1975), n.p.

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 438

Zhao Ziyang, “Zai Sichuan shengwei changwei kuoda huiyi zhaojiren huiyi shang de jianghua” [Speech at the Conveners’ Meeting of the Enlarged Session of the Standing Committee of the Sichuan Provincial Party Committee] (January 9, 1979), unpublished internal document, n.p.

Zhang Guangyou, Fengyun Wanli [Wan Li in Turbulent Times], 1st ed. (Beijing: Xinhua Press, January 2007), 164.

Wan Li, Wan Li lun nongcun gaige yu fazhan [Wan Li on Rural Reform and Development], 1st ed. (Beijing: China Democracy and Legal System Press, October 1996), 82.

Du Runsheng, ed., Zhongguo nongcun gaige juece jishi [A Documentary History of Decision-Making on China’s Rural Reform] (Beijing: Central Party Literature Press, 1998), 373–82.

Guo Shutian, ed., Huainian lao lingdao wenji [Collected Essays in Memory of Senior Leaders] (Beijing: Agricultural Economics Institute, China Academy of Management Science, June 2019), 59.

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 440

Zhang Huaiying, Dazhai: Chen Yonggui [Dazhai and Chen Yonggui], 1st ed. (Beijing: China Culture Communication Press, September 2013), 265.

Duan Yingbi, Wo suo qinli de nongcun biange [The Rural Transformation I Personally Experienced], 1st ed. (Beijing: China Agriculture Press, July 2018), 157.

Sheng Ping, ed., Hu Yaobang sixiang nianpu [Chronicle of Hu Yaobang’s Thought], vol. 1, 1st ed. (Hong Kong: Tide Times Publishing Co., April 2007), 527.

Du Runsheng, ed., Zhongguo nongcun gaige juece jishi [A Documentary History of Decision-Making on China’s Rural Reform], 1st ed. (Beijing: Central Party Literature Press, January 1999), 133.

Zhao Shukai, “Nongyanshi de yanbian” [The Evolution of the “Rural Policy Research Office”], Zhongguo fazhan guancha [China Development Observation], no. 9 (2018), n.p.

Party Literature Research Office of the CPC Central Committee and Development Research Center of the State Council, eds., Xin shiqi nongye he nongcun gongzuo zhongyao wenxian xuanbian [Selected Important Documents on Agricultural and Rural Work in the New Period], 1st ed. (Beijing: Central Party Literature Press, October 1992), n.p.

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 436

Zhang Guangyou, Fengyun Wanli [Wan Li in Turbulent Times], 1st ed. (Beijing: Xinhua Press, January 2007), 120.

Editorial Group for Selected Works of Wan Li, Minutes of the Editorial Group Meeting for Selected Works of Wan Li (August 1994), unpublished internal document, n.p.

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 437

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 439

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 441

General Office of the State Agricultural Commission. (1980, March). Meeting materials of the General Office of the State Agricultural Commission [Unpublished internal document].

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 441

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 441

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 439

Vogel, Deng Xiaoping, 806

Gu Jiegang, Gushi bian zixu [Preface to Doubts on Ancient History], vol. 1 (Beijing: The Commercial Press, December 2011), 164.

Yang Lien-sheng, review of Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 1: Introductory Orientations, by J. Needham, with research assistance from Wang Ling, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 18, nos. 1–2 (June 1955): 270–83, at 283.

p.s. This translation contains 42 footnotes rather than the 44 found in the original Chinese article. The discrepancy arises because the Chinese version required extra citations to compare conflicting translations across different versions; since this English text reverts directly to Vogel’s original wording, those comparative notes became redundant and were consolidated.

Zhao Shukai: Ghostwriters of Reform

Behind China’s big policy documents and set-piece speeches stands an anonymous guild of wordsmiths whose drafts have nudged the course of reform as surely as any the leaders who sign them. One of them, veteran rural-policy insider Zhao Shukai, looks back on four decades in the engine room of official document writing to reflect on what it means to “danc…