Part II: David Daokui Li's meticulous breakdown of "nested" dimensions of local govt & its debt

The nested structure, where parent companies borrow funds to secure loans for subsidiaries greatly amplifies the intricacy and magnitude of local government debts in China, says economist at Tsinghua.

In a post on Friday, Dec. 22, we shared that Professor David Daokui Li of Tsinghua University recently unveiled a study - together with Zhang He at the Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking (ACCEPT) - that found China’s local government debt in 2020 was around 90 trillion yuan, 50% higher than World Bank and IMF estimates.

China's local govt debt in 2020 was 50% higher than WB, IMF estimates: David Daokui Li

Local government debt in China amounted to 90 trillion yuan (12.49 trillion U.S. dollars) in 2020, 50% higher than the World Bank and IMF estimates, according to a recent study by Professor David Daokui Li and Zhang He of the Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking (

Li, Mansfield Freeman Chair Professor of the Department of Finance of the School of Economics and Management of Tsinghua reported that none of the existing methodologies offer an accurate way of measuring local government debt in China, so he and his team devised a new one. This method, grounded in case studies and an in-depth examination of the debt structure of local governments, revealed that:

The majority of local government debts in China are infrastructure debts.

A significant portion of this infrastructure debt is accrued by local State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs).

China's local government debt demonstrates a nested structure, where local governments establish entities to secure loans, and these entities, in turn, leverage those borrowed funds to acquire further financing for their subsidiaries.

The following article is the second part of the translation of Prof. Li's lecture at the 8th session of the "Government and Market Economics Series," an event organized by ACCEPT at Tsinghua University on Oct. 25.

The full video of Li's lecture is available at Xueshuo, a professional knowledge dissemination platform incubated by Tsinghua. (Watching requires registration.) A transcript of his lecture appears to be first published by the New Economist WeChat blog.

How large is the scale of local government debt?

Now, let's discuss our method for measuring China's local government debt, analyzing its scale, structure, and sustainability.

First of all, we believe that the existing literature does not accurately measure local government debt. We identified three prevailing methods in the literature for measuring local government debt:

Debtor method, which aggregates various types of debt, including municipal bonds and other forms of local government debt.

Funding source method, which examines the sources of funding for all investment projects, such as bank loans, bonds, non-standard financing, and Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs).

Public savings method, which calculates new debt as the difference between government investment expenditures and government revenues.

We believe each of these methods has its pros and cons, and none offer a completely accurate picture.

First, the debtor method is challenging due to the multitude of debtors involved, and many entities like local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) are not captured in this method. Furthermore, not all debts of LGFVs are not related to governmental activities. Some are linked to investments in private companies, like Nio, which should not be classified as governmental debt.

Second, the government finance government finance involves a myriad of transactions, which significantly add to the difficulty of balancing the books, and also, adopting the funding source method or the public savings approach.

Frankly speaking, local government officials, even a mayor or deputy mayor might not have a clear idea of their debt situation unless directly involved in the city's financing activities.

Therefore, we took a novel approach by focusing on the allocation of debt funds, which provides a more precise understanding of how these debts are utilized across various sectors such as social welfare, infrastructure investment, affordable housing, and others. This method draws on data from reports and regulations issued by the National Audit Office and the Ministry of Finance between 2013 and 2019.

We categorized local government debt into 1) infrastructure, 2) affordable housing, 3) land acquisition, 4) science, education, culture, health, and other sectors, and calculate each separately. Apparently, debts arising from infrastructure projects and affordable housing count as government expenditures. Notably, in the Chinese context, local governments typically retain the property rights of affordable housing, which differs from Western practices. Science, education, culture, and health debts are direct expenditures without corresponding assets, much like those in the West.

Our methodology began with an analysis of infrastructure spending. We estimated the proportion of local government infrastructure investment funded through debt and then aggregated this financing year by year. Of course, we also accounted for their debt repayments.

We selected some typical cases, including Chongqing and Kunming, among others. The rationale for selecting case studies is to ascertain the ratios of many crucial parameters that are otherwise indeterminable without specific examples. For instance, we examined scenarios like a local government undertaking a subway project to determine what percentage of the financing is typically borrowed by the subway company, the debt ratio of the parent company of the subway company, and the financing mechanisms of the grandparent company.

The aim was to calculate these ratios accurately. By selecting typical cases, we derived certain coefficients and applied them nationwide to provide a more accurate and representative analysis. You can't just make assumptions at the macro level, but it's also not feasible to analyze every single city and region in such detail.

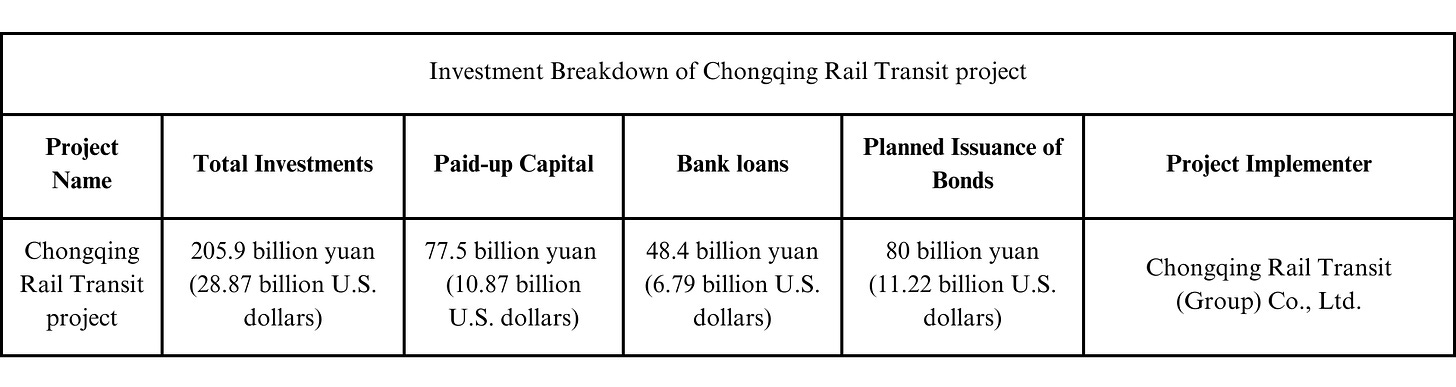

We looked at the Chongqing Rail Transit project in 2020, which had a total investment of 205.9 billion yuan (28.87 billion U.S. dollars). To put this in perspective, it's comparable to the cost of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge.

The project's paid-up capital was 77.5 billion yuan (10.87 billion U.S. dollars), with 48.4 billion (6.79 billion U.S. dollars) borrowed from financial institutions, leaving a funding gap of 80 billion yuan (11.22 billion U.S. dollars) to be covered by bond issuance. As illustrated in this table below, the structure of the funding was as follows: 77.5 billion yuan in capital, 48.4 billion yuan in bank loans, and 80 billion yuan in publicly issued bonds.

Now, the question arises: where did this 77.5 billion yuan in capital come from? That was the goal of our research. We looked into the parent company of the Chongqing Rail Transit (Group) Co., Ltd., the Chongqing City Transportation Development & Investment Group Co., Ltd., abbreviated as Chongqing Develop & Investment. So, the 77.5 billion comes from Chongqing Develop & Investment.

Now, where did Chongqing Develop & Investment get this money? Part of it comes from their own group's debt funds, and another part comes from government appropriations.

We further investigated Chongqing Develop & Investment's debts for the rail transit project. They had issued several bonds over the years: 1 billion yuan (140 million U.S. dollars) in corporate bonds in 2006, 2.8 billion (393 billion U.S. dollars) in 2010, 3 billion (421 million U.S. dollars) in medium-term notes in 2011, and another 3 billion in 2012, totaling 9.8 billion yuan (1.37 billion U.S. dollars). These bonds had varying maturities of 10 and 5 years.

Thus, Chongqing Develop & Investment's capital came from two sources: direct governmental funds and government debt. They raised government debt under the name of the Chongqing Municipal People's Government and invested these funds, along with direct government grants, into Chongqing Develop & Investment as capital.

So, let's sum up the financial analysis of the Chongqing Rail Transit project. The total project investment was 205.9 billion yuan (28.87 billion U.S. dollars). The total liabilities were 176.1 billion yuan (24.69 billion U.S. dollars), of which 80 billion (11.22 billion U.S. dollars) was government special bonds, and 48.4 billion (6.79 billion U.S. dollars) was borrowed from financial institutions. About 77.6 billion yuan (10.88 billion U.S. dollars) was capital provided by the parent company, of which 47.6 billion (6.67 billion U.S. dollars) was debt within the capital itself, in other word, borrowed by the parent company. This is of most significance.

We further dissected this 47.6 billion yuan: 9.8 billion (1.37 billion U.S. dollars) was debt issued by Chongqing Develop & Investment, 1.2 billion (168 million U.S. dollars) was long-term borrowing by Chongqing Develop & Investment, 14 billion (1.96 billion U.S. dollars) in equity instruments with fixed principal and interest obligations, and 22.6 billion (3.17 billion U.S. dollars) in local government bonds.

The construction of the Chongqing Rail Transit is indeed a significant endeavor, and there is nothing wrong with undertaking such infrastructure projects. The question is how debts within these projects are supposed to be resolved. I will address this question in the final part of my lecture.

In summary, through meticulous analyses, it becomes evident that out of the total investment of 205.9 billion yuan (28.87 billion U.S. dollars) infrastructure project, 85% of the funds were debt-financed, with only a portion being direct governmental funding.

That is to say, the debt in infrastructure investment projects equals the debt outside the project's capital plus the debt within the capital. When you put these together, the capital itself also includes debt: the parent company's debt, plus the government debt within the parent company's own funds. The parent company borrows money and invests it in the subsidiary, and within this capital, there is also government-borrowed money. I hope I have made myself clear.

Perhaps I can put it like this: the "child" project, which is the rail transit project, borrowed some money from the parent company, which is the development company. However, a significant part of the money injected by the parent's company was also borrowed. Moreover, the capital of the parent's company includes money borrowed from the government.

This is a nested situation. The government incurred a debt, so it registered the parent company to secure additional loans. Consequently, when the parent company invested in the "child" or even "grandchild" company, it essentially transmitted the multi-tiered debt relationship downstream.

The government borrows money, the parent company borrows money, and the subsidiary also borrows money. So, when you break it all down, the amount is quite significant. This forms a major part of our work. Hence, based on typical cases in various places, we have come up with a basic estimation method.

[The following section of Prof. Li's speech is an introduction of parameters, information sources, calculation techniques, and other nuances in the estimation method employed in his study. This more technical section has been omitted for brevity due to space constraints.]

As you can see, the graph on the left illustrates the total amount of debt of local governments. They were allocated across various sectors, encompassing infrastructure construction, affordable housing initiatives, land acquisition and reserves, as well as projects in the domains of science, education, culture, and health.

In the three lines in this graph below, the solid blue one in the middle is the median, which we consider to be the most reliable indicator. The grey dashed line above is what we consider the maximum, representing the upper limit, while the orange line below signifies the lower limit, thereby illustrating a range.

Take the year 2020 as an example. We estimate that the total amount of local debt in China for 2020 was 89.53 trillion yuan (12.6 trillion U.S. dollars). The upper limit is estimated at 100 trillion yuan (14.7 trillion U.S. dollars), and the lower limit at 75 trillion yuan (10.55 trillion U.S. dollars, both quite high figures.

The graph below shows the debt-to-GDP ration of local governments. According to our formula, we believe the most reliable figure for the total amount of local debt in 2020 is 89.5 trillion yuan (12.59 trillion U.S.dollars), close to 90 trillion yuan (12.66 trillion U.S dollards), which is 88% of GDP. This is the magnitude of the figure.

As I've previously presented, infrastructure debt is the most prominent category of local government debt in China. The total amount of infrastructure debt might even be higher than corporate debt.

In 2020, the balance of infrastructure debt incurred by local State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) was 50 trillion yuan (7.03 trillion U.S. dollars), and for affordable housing, it was 5 trillion yuan (703 million), totaling 55 trillion yuan (7.74 trillion U.S. dollars).

Therefore, of the 90 trillion yuan total local government debt I mentioned earlier, 55 trillion yuan was borrowed through local SOEs. We firmly believe, despite potential minor disagreements with certain scholars and some official statistics, that the debts of local SOEs are essentially part of local government debts.

These SOEs exist not to produce refrigerators or cars but to raise debt for infrastructure projects, providing debt-raising services for the government. So, we must recognize these as local government debts, and this is where our analysis differs from many others.

I've already shown you this chart. Pay attention to the blue line; it remained stable until 2015. Prior to 2015, the local government's capacity to repay debt was satisfactory, reaching approximately 5.5%. This implies that before 2015, the combination of fiscal surpluses from local governments and profits generated by local SOEs could cover approximately 5.5% of the interest on local debt. The situation was relatively balanced, and a 5.5% interest rate was manageable.

However, it plummeted dramatically starting in 2015 due to increased borrowing and a rapid increase in the denominator, dropping to 1.6%. By 2020, it fell to 2.15%, and I suspect the figure is even lower now, given the current economic circumstances, which are more challenging than in previous years.

What I just described is my team's detailed measurement of the total scale of local government debts. In summary, there are two conclusions:

First, in 2020, the local government debt amounted to 90 trillion yuan, accounting for 88% of the GDP.

Second, a qualitative conclusion: the majority of local government debts are infrastructure debts, and a significant portion of infrastructure debt is accrued by local SOEs. The principal mechanism behind local SOE debt involves a nested layering approach - setting up companies at one level, borrowing funds, using the borrowed capital to secure additional loans at the next subsidiary level, thereby amplifying debt layer by layer.

In corporate finance theory, it's often said that prominent shareholders use nested structures to amplify their control. For example, a parent company holding 50% of shares might create a subsidiary to exert influence over the remaining 50%. Our analysis suggests that local governments borrow money through a similar nested structure of local SOEs. However, the objective here is not to control shares but to facilitate borrowing.

The remaining portion of David Daokui Li's lecture, in which he delves into the measurement of local government debt using game theory and outlines specific strategies for addressing this issue in China, will be released shortly.

In the meantime, The East is Read has already published a series of articles that explore the gravity of, the causes behind, and the possible solutions to China's debt challenge. I invite you to explore these articles for a more comprehensive understanding of the local government debt situation in China.

— Jia Yuxuan

China's local govt debt in 2020 was 50% higher than WB, IMF estimates: David Daokui Li

Local government debt in China amounted to 90 trillion yuan (12.49 trillion U.S. dollars) in 2020, 50% higher than the World Bank and IMF estimates, according to a recent study by Professor David Daokui Li and Zhang He of the Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking (

Zhang Ming says local govt handicapped by short-term, high-interest debt, & unaffordable responsibilities

Local government debts in China—their causes and solutions—have been a subject of internal debate for months, and has frequently been featured on The East is Read. In a recently published piece, Ting Lu, Chief Economist of Nomura Securities China, identified revitalization of the real estate sector as a key measure to kickstart debt resolution in China.

Ting Lu: urbanization+real estate is key to debt resolution

This article features the speech of Mr. Ting Lu, Chief Economist of Nomura Securities China, from his recent discussion in the New Economist Think Tank Debt Debate (Part Two). The original Chinese version is available on the WeChat blog of New Economist Think Tank.

Xu Gao: China's historical, unitary framework implies central govt responsibility for local govt debt

The unitary political framework, a millennia-old legacy in China, obligates the central government to intervene in local government debt, which is a key component of the country's growth model, said Xu Gao, the Chief Economist of Bank of China International (China).

Beyond LGFVs: three types of hidden debt unaccounted for in China's official stats

The debts accumulated by Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs), often referred to as China's hidden debts due to their association with government liability, are widely known among observers of China's economy. However, in a recent speech and Q&A

Luo Zhiheng on government debts, fiscal expenditure, and major risks

Luo Zhiheng 罗志恒 is the Chief Economist and President of the Research Institute at Yuekai Securities and one of China’s leading scholars on macroeconomics and fiscal policies. He sat at Li Qiang, Chinese Premier’s roundtable on Jul. 6. Although what he said was not disclosed, the following

Thanks, interesting. This kind of “nested financing” is commonly used in Western countries. It’s usually called “project finance”. The reason for the nested structure is (at least in the West) not to expand the amount of leverage, but really to give some creditors priority over other creditors. If the loan is made directly to the project, then it is paid directly out of the project. Whereas loans to the parent are repaid by the parent, only after paying off the project loan. So project creditors take priority over parent creditors.

I am not sure what the motivation for the nested structure in China was. But if lenders were prudent and did their proper due diligence, they would “see through” the nested structure and take it into account in deciding how much to lend. At the end of the day, the loans have to be repaid by the project and so lenders would (if they were prudent) not increase the amount they lend simply because of the nested structure.

Great work, but incomplete,

We see the asset side of local governments' ledgers.

(Brad Setser, for example, claims that Beijing is sitting on $9 trillion in foreign exchange assets, $6 trillion of which is undeclared).