Xu Gao: China's historical, unitary framework implies central govt responsibility for local govt debt

There's no moral hazard: Chief Economist of Bank of China International (China) breaks down China's local govt debt into three dimensions: data, the "China model", and central-local govt relationship.

The unitary political framework, a millennia-old legacy in China, obligates the central government to intervene in local government debt, which is a key component of the country's growth model, said Xu Gao, the Chief Economist of Bank of China International (China).

Xu Gao's article, in full translation below, delves into China's local government debt issues across three dimensions: data, the "China model", and central-local government relationship. He suggests that the central government issue bonds to replace local government debt that falls outside the scope of national bonds. This proposal aims to support the Chinese government's goal of achieving a "comprehensive debt resolution package," according to Xu, which has received limited clarification in terms of practical implementation.

Rapid GDP growth is essential to China's pursuit of high-quality development, Xu says. Local government debt, an integral element of the capital-oriented, business-style urban management model adopted by local governments, in conjunction with land finance, confers distinct advantages upon the "China model" which features infrastructure investment. This combination serves as a pivotal catalyst propelling the nation's rapid economic advancement.

In a unitary state like China, where the central and local governments share unlimited mutual responsibility, it is incumbent upon the central government to provide timely assistance to local governments when they face challenges. This responsibility becomes even more pronounced in the wake of local governments grappling with three years of COVID pandemic and the property market setback. Xu believes it is imperative that the central government intervenes to support local government debt, thereby preventing risks from escalating.

Xu Gao is the Chief Economist of Bank of China International (China) Co., Ltd. and an adjunct professor of National School of Development in Peking University. Xu has also published two best selling textbooks in China — "Lectures on Macroeconomics from a Chinese Perspective" and "Lectures on Financial Economics".

The following article was originally published on Tsinghua Financial Review, Issue 10, 2023. A longer version with an abstract and references can be found on Xu Gao's personal WeChat blog.

Currently, local government debt and the real estate sector stand as the two central focal points in China's domestic economy. In the Politburo meeting on July 24th, top leaders called for the "development and implementation of a comprehensive debt resolution package." As debt resolution policies go into effect, discussions on local government debt have intensified. This article examines local government debt issues from three dimensions: data, the "China model", and the central-local government relationship; it also aims to provide recommendations for a comprehensive debt resolution package. While China's government debt is sustainable and the overall volume on a reasonable scale, there are significant structural imbalances, with the share of central government debt notably low and that of local government debt excessively high.

Given the vital role that local government debt plays in propelling China's economic growth and the intricacies of the central-local government relationship within China's "unitary" political framework, an effective approach for a comprehensive debt resolution plan involves the central government issuing national bonds to replace local government debt outside the scope of national bonds.

Data Dimension

China's government debt, when examined from a data perspective, demonstrates two main characteristics: the total volume is not excessively large, and the share of central government debt is significantly low.

As of the end of 2022, China had a total of 25.9 trillion yuan (3.55 trillion USD) in central government debt (measured using national bonds), 35.1 trillion yuan (4.81 trillion USD) in local government bonds issued by the central government (also measured using national bonds), and 12.4 trillion yuan (1.70 trillion USD) in "municipal investment bonds" issued by Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs).

The term “local government bond” refers to the bonds of a local government for 2009 which shall be issued and repaid by the government of a province, autonomous region, municipality directly under the central government or cities specifically designated in the state plan but are issued by the Ministry of Finance on its behalf with the principal, interest, and issuance costs being paid by the Ministry of Finance also on its behalf, upon the approval of the State Council.

— Article 2, Measures for the Budget Administration of the Local Government Bonds for 2009, Ministry of Finance of China

Among these components, the latter two should be categorized as local government debt. Together, these three components account for roughly 60% of China's GDP in 2022. However, when it comes to deciding which other debts should be included in the local government debt category and, consequently, in the overall government debt, different opinions have led to varying estimates of China's total debt size.

Under different definitions, estimates of China's government debt-to-GDP ratio vary, ranging from low to high. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) estimated it at 78% for 2022, Zhang Ming estimated 93% for 2021, Yang Yewei and Wang Chunyi estimated 95% for 2022, Sun Binbin and Meng Wanlin estimated 108% for 2022, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated 110% for 2022.

Despite these differences in estimated figures, they collectively present a consistent picture. Using the BIS' international debt data as a reference, China's total debt size appears within a reasonable range, falling between the average levels of emerging market countries and developed countries. Even the highest estimate by the IMF places China's government debt-to-GDP ratio at approximately the average level of developed countries (notably lower than Japan's 228% debt-to-GDP ratio). Additionally, the Chinese government holds significantly more assets than other governments, and the country boasts a savings rate nearly double the global average. These factors suggest that China's government debt size is relatively secure.

In reality, the key determinant of government debt sustainability does not lie with the size of the debt but rather factors like inflation and international trade balances. As long as inflation remains subdued and international trade remains robust, domestic demand will not outstrip supply capacity, ensuring sustainability of domestic government debt. Presently, China faces deflationary pressures and consistently maintains a current account surplus, so the sustainability of China's government debt does not pose as a problem.

However, within the context of an overall healthy government debt level, the significant disparity between central government debt (low) and local government debt (high) in China merits attention. Based on data from the IMF's Global Debt Database (GDD), the 2022 average share of central government debt in total government debt worldwide stands at 89%, with a median of 96%. This means that in most countries, government debt is primarily composed of central government debt. In contrast, the share of central government debt to total government debt in China ranges from 19% to 27%, by different calculation methods — significantly lower than the global norm. Even if local government bonds issued by the central government were categorized as part of central government debt, this ratio would only increase to a range of 46% to 65%, still below the international average.

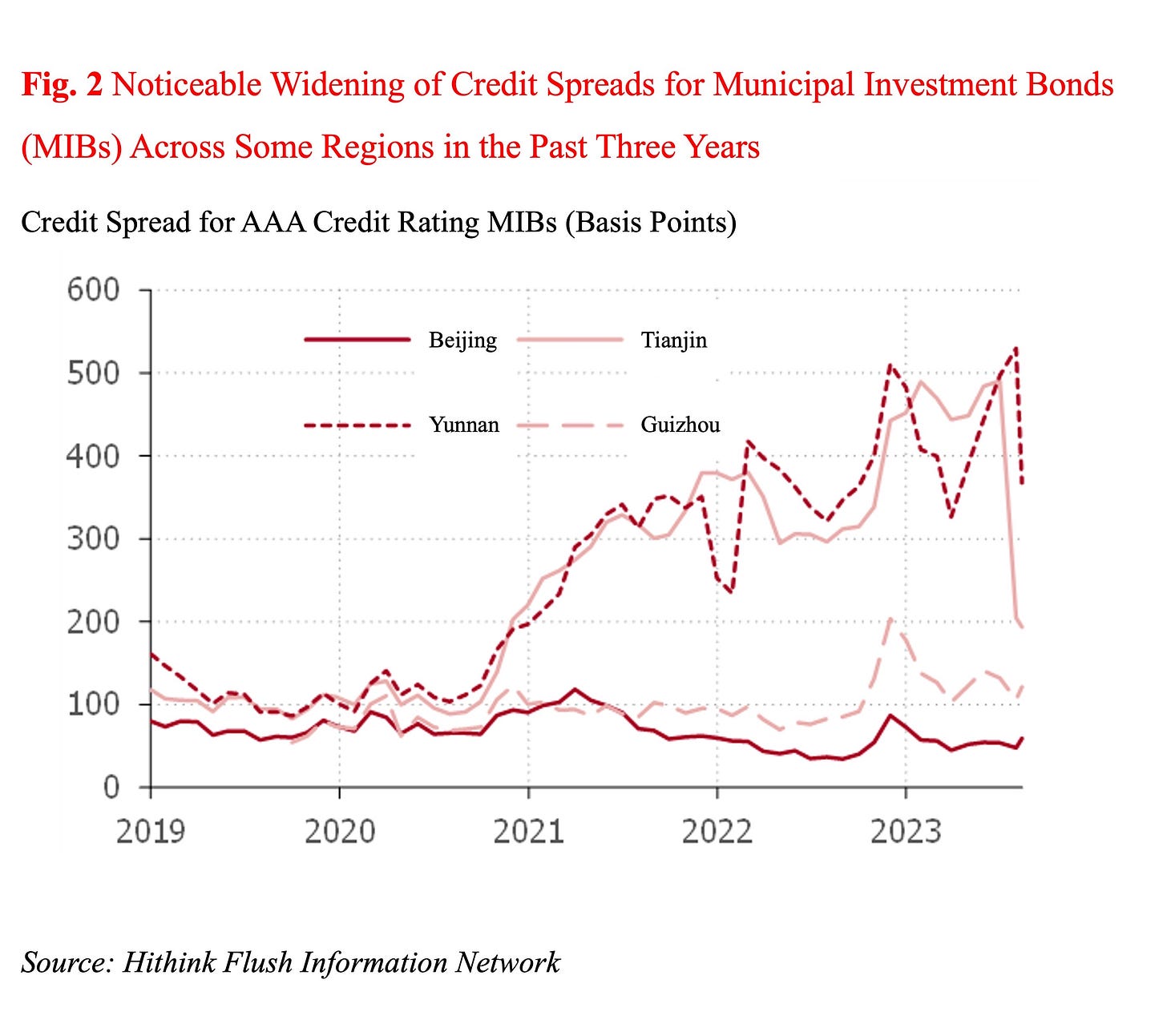

Compared to national bonds issued by the central government (including local government bonds issued by the central government), local government debts in China are incurred through myriad channels, suffer from a lack of transparency, and carry relatively high financing costs. Consequently, while the overall volume of China's government debt may not be problematic, there is indeed significant debt risk in the local governments of certain regions. Starting in 2020, interest rates on local government investment bonds in some regions have witnessed sharp increases, leading to widened yield spreads and indicating the local government debt risks in these areas.

The "China Model" Dimension

Mere cross-national data comparisons fall short to truly understand local government debt in China. It's essential to contextualize local government debt within China's unique development model and gain a more profound understanding of its origins. Local governments in China borrow to fund regional investment, thereby driving regional economic growth. The expansion of local government debt largely stems from their eagerness to boost GDP.

The pursuit of GDP growth by local governments is not misguided. GDP isn't just a quantity indicator of economic output; it also serves as a quality indicator, reflecting how people assess the achievements of economic development. This is because GDP represents the total market value of all final outputs, calculated at market prices; these prices are formed during market transactions and therefore reflect people's preferences; the higher the demand, the higher its price. In this vein, the aggregation of the total value of all final outputs at market prices is equivalent to an overall value assessment of these outputs by the people. Currently, China is striving for "high-quality development," and no one has a more significant say than the entire population who vote with their hard-earned money. That is to say, no indicator is more accurate than GDP. Therefore, high-quality development requires rapid GDP growth, and rapid GDP growth is the foundation of high-quality development.

In 1992, during his southern tour, Deng Xiaoping introduced three criteria for evaluating policies, "that it must benefit the development of the socialist productive forces, be conducive to increasing socialist China’s overall strength, and help to improve the people’s living standards." Without a doubt, policies aimed at achieving GDP growth align with these three criteria.

In the pursuit of GDP growth, an essential phenomenon has emerged among Chinese local government officials—an "promotion tournament." It holds tremendous significance for China's economic development. In 2007, Zhou Li-An published an influential article titled "Governing China's Local Officials: An Analysis of Promotion Tournament Model" in the the Economic Research Journal. According to CNKI, this article has been cited over 9,400 times. In this article, Zhou Li-an wrote, "The promotion tournament based on economic growth combines the unique nature of China's government system and economic structure. It offers a governance model with Chinese characteristics, in which local officials who possess significant administrative power and discretion can be motivated to drive local economic development." Zhou further emphasized that this promotion tournament, based on economic growth and with GDP as the primary performance indicator, has transformed local governments in China into "partners" in economic development, rather than "exploitative entities" found in many other developing countries, making it a crucial foundation of China's economic miracle. Local government debt, as a critical resource supporting local government officials in this "GDP tournament," plays an indispensable role in China's economic development.

In fact, local government debt is an essential element of the "China model." Over the past four decades of reform and opening up, the phenomenal improvement in China's infrastructure has emerged as a widely recognized achievement, both by the Chinese populace and foreigners. The rapid advancement of infrastructure has provided robust support for China's economic development. In this regard, with local government debt playing an indispensable role. The majority of infrastructure projects serve a public good, and the benefits they generate primarily manifest as positive externalities, which are difficult to translate into direct financial returns for the projects themselves. As a result, while infrastructure is of utmost importance, it is not a lucrative business. This presents a common challenge shared obstacle by numerous countries, including developed ones, where financing constraints impede the execution of large-scale infrastructure projects.

Unlike these many countries, urban land in China is government-owned. Therefore, even though the social externalities of infrastructure investment are seldom convertible into financial returns, the projects can still profit through the government's receipt of increased land values, hence the establishment of the capital-oriented, business-style urban management model based on land finance and local government debt. Local governments would borrow to fund infrastructure investments (mainly through LGFVs), then monetize the social benefits of infrastructure investments through land sales and repay the debt borrowed earlier. This way, despite micro-level profitability challenges for individual infrastructure projects, the government can still effectively reconcile its cost-benefit equation.

Those who fail to understand this interconnectedness tend to segregate infrastructure investment and land finance, focusing solely on their individual problems. However, those acquainted with the "China model" recognize that these two elements can combine to form a viable and sustainable business model for infrastructure investment — an invaluable asset behind China's mega infrastructure projects and a wondrous tool that other countries would dream to obtain. And local government debt is pivotal to this mechanism.

Of course, due to the exact necessity of combining local government debt with land finance for effectiveness, local government debt has become a severe issue over the past two years as the real estate sector spirals down a vicious cycle of financing tightening. However, this should not be a justification for rejecting local government debt. Dismissing local government debt in addition to failing to tackle and rectify the real estate issues would only compound the mistake.

Central-Local Government Dimension

When analyzing China's local government debt, it's essential not to overlook the dynamics of fiscal relations between the central and local governments. The current challenges with local government debt and their future solutions are both closely intertwined with the central-local government relationship.

Some argue that resolving local government debt issues requires balancing revenues and duties of local governments. [China'a tax-sharing reform in 1994 allocated 75% of value-added tax (VAT) to the central government, and 25% to the local governments, a measure long complained about by local governments. VAT is one of the largest income sources for the Chinese government, particularly due to limited contributions from personal income tax.] The underlying assumption here is that as long as local government fiscal revenues match their expenditures, deficits will be eliminated, and local governments will no longer need to resort to debt issuance. However, this oversimplification fails to grasp the current situation and historical context.

Major tax types directly related to economic development are shared between the central and local governments. Tax types suitable for local management are designated as local taxes, with efforts to enrich the variety of local taxes and increase local tax revenue. The specific categorization is as follows:

Central Fixed Income: Customs duties, consumption tax and value-added tax collected by customs on behalf of the central government, consumption tax, central corporate income tax, income tax from local banks, foreign-funded banks, and non-bank financial enterprises, income collected centrally from railway departments, various central bank headquarters, and major insurance companies (including business tax, income tax, profits, and urban maintenance and construction tax), profits turned in by central enterprises, among others.

Local Fixed Income: Business tax (excluding business tax collected centrally by railway departments, various central bank headquarters, and major insurance companies), local corporate income tax (excluding the above-mentioned income tax from local banks, foreign-funded banks, and non-bank financial enterprises), profits turned in by local enterprises, personal income tax, urban land use tax, fixed asset investment orientation adjustment tax, urban maintenance and construction tax (excluding the portion collected centrally by railway departments, various central bank headquarters, and major insurance companies), property tax, vehicle and vessel tax, stamp duty, slaughter tax, agriculture and animal husbandry tax, agricultural specialty product revenue tax, land occupation tax, deed tax, inheritance and gift tax, land value-added tax, revenue from compensated use of state-owned land, and others.

Central and Local Shared Income: Value-added tax, resource tax, and securities transaction tax. For value-added tax, the central government receives 75%, while local governments receive 25%. Resource tax is categorized based on different resource types, with the majority being allocated to local income, and oceanic petroleum resource tax being allocated to central income. For securities transaction tax, both the central and local governments share equally, each receiving 50%.

— December, 1993, The State Council's Decision on Implementing the Fiscal Management System of Tax Sharing

On the one hand, as discussed earlier, local government debt is an integral part of the urban management model employed by local governments, so it isn't inherently tied to whether government revenues and duties are in equilibrium. Of course, shortage of expenditures would certainly add to the motivation behind local government debt.

On the other hand, the balance of revenues and duties between local and central governments should not and is unlikely to reach equilibrium in the future. Before the 1994 tax-sharing reform, fiscal revenues and duties between local and central governments were balanced because of the fiscal responsibility system [which required local governments to remit fixed amounts of revenues to the central government while retaining the remaining balance under their own control].

However, this equilibrium came at the cost of low fiscal revenues and limited nationwide capacity for the central government. On September 16, 1993, then Vice-Premier Zhu Rongji [who became Premier 1998-2003] emphasized in his speech "Tax-Sharing Reform Will Promote Guangdong's Development", that "the purpose of tax-sharing reforms is to resolve the central government's financial difficulties. Currently, the central government is in dire financial straits, to the point where it can barely make ends meet. The central government will no longer be able to sustain itself if central fiscal revenues are not concentrated appropriately and central financial strength is not enhanced. Ultimately, the entire country will suffer and cease to progress." In another speech titled "Tax-Sharing Reform Benefits the Development of the Central and Western Regions" on September 25, 1993, Zhu further underscored, "Wealthy regions should contribute to poorer regions. The rich will become richer and the poor will become poorer if the central government doesn't collect taxes. Comrade Deng Xiaoping called for common prosperity. To be honest, this is the biggest reason for tax-sharing reforms."

Zhu Rongji's statements unequivocally indicated that the tax-sharing reform was designed to bolster the central government's financial capacity, enabling it to facilitate more substantial fiscal transfers between regions and mitigate regional development disparities. Subsequent to the tax-sharing reform, the central government notably augmented its fiscal transfers to the central and western regions. The less developed an area was, the higher the share of fiscal support it received from the central government for expenditures. This served to narrow regional disparities and ensure unity and stability across the country.

It is fair to say that the principle of less revenues than duties for local governments, and correspondingly, greater revenues than duties for the central government, is a traditional political wisdom in China, rooted in its millennia-long history as a highly centralized state. This historical legacy has solidified China's status as a "unitary" state. The article titled "China's Legislative System" on www.gov.cn explicitly declares, "China is historically formed to be a unified and unitary state." [The summarized English version, unfortunately, omits this sentence.]

In a unitary state, various administrative units derive their powers from the central government and do not possess inherent sovereignty. Local governments at all levels function as mere agencies of the central government and are not independent political entities. In other words, China has only one government, which is the central government. In China, the relationship between the central government and local governments is more akin to the relationship between the brain and the limbs rather than two independent market entities. The central government bears unlimited responsibility for local governments, and local governments similarly bear unlimited responsibility for the central government.

Therefore, from a legal perspective, China has only one source of government credit, which is the central government; all debts incurred by local governments are, in fact, debts of the central government; any default by a local government imperils the central government's credit. In other words, a default by any single local government would lead to a systemic crisis, triggering a widespread sell-off of debts of all local governments, including the central government. Consequently, local government debt entails only systemic risks, not individual ones. Relying on market mechanisms to impose varying constraints on local government debt issuance is wishful thinking. Currently, the differentiation in yields of local government bonds does not necessarily result from the effectiveness of market constraint mechanisms; it may be signs of the weakest link collapsing at the start of a chain reaction.

The concept of "moral hazard" frequently arises in discussion on local government debts. "Preventing 'Moral Hazards' in the Management of Local Government Debt" authored by Zeng Jinhua (2018) and posted on the website of China's Ministry of Finance elaborates on this concept. The article states, "In the management of government debt, due to the possibility of the superior government 'backing' the subordinate government, 'moral hazards' can arise, meaning that local governments may issue debt indiscriminately since they are not required to bear the risk... Many countries strengthen budget constraints on local governments and clarify debt responsibilities to prevent local governments from having the mentality of expecting central government bailouts, which can lead to 'moral hazards' and the transfer of debt risks from local governments to superior governments." In recent years, preventing moral hazards has been one of the important reasons why the central government refuses to bail out local government debt.

However, the concept of "moral hazard" has a strict definition and should not be used indiscriminately. In The Economics of Contracts by Bernard Salanie (2ed Edition, 2005), the opening of the chapter "Moral Hazard," clearly defines three essential components of moral hazard:

The third component, in plain terms, implies that the party with information advantages tends to misuse them for wrongdoing, thus creating moral hazard. Conversely, if the party with information advantages tends to do the right thing, there is no moral hazard problem. Rather, information advantages are being appropriately used to enhance economic efficiency.

Therefore, when people discuss local government debt using the concept of moral hazard, they are essentially presupposing that local government debt issuance is a bad thing and that local governments are "bad agents". Based on the above analysis, such an assumption is clearly inappropriate. It can be said that those who discuss local government debt in terms of moral hazard misunderstand local government debt from the start, fail to recognize its contribution to China's economy, and do not fully realize the significant role local governments play in driving economic development.

Perhaps it is this mindset that has limited the space allocated to local governments in China's government bonds. It is only in recent years that the central government issues bonds on behalf of local governments. Even so, local governments have to continue financing through unofficial "back doors" since the "front door" of government bond issuance isn't open enough to meet their needs. This is one of the reasons why China's central government debt accounts for a relatively small share of total government debt by international comparisons. Under these circumstances, the central government should not only issue national bonds to replace existing local government debt but should also increase the issuance of national bonds in the future to provide ongoing support for local governments in terms of new debt. Moral hazards should not be used as a basis for curbing local government debt issuance demands, as such restrictions can not resolve the debt problem and are detrimental to economic development.

China is a unitary state with central and local governments bearing unlimited mutual responsibility. This reality is impossible to be sidestepped using concepts like moral hazard or "tightening budgetary constraints". A straightforward question is: If the central government insists on the principle of "parents feeding their own children 谁家的孩子谁抱," [implying that local governments must independently bear the responsibility for their own debts and not anticipate central government bailouts] can local governments opt to refuse the "child" of the central government in the future?

Clarify performance management responsibilities and constraints. In accordance with the unified deployment of the Party Central Committee and the State Council, the Ministry of Finance shall improve the responsibility and constraint mechanism for performance management. Local governments at all levels and various departments and units are the responsible entities for budget performance management.nits, and project managers are responsible for the budget performance of their projects. For major projects, a performance-based lifelong accountability system is implemented for project managers, ensuring effective expenditure scrutiny and accountability for inefficiency.

— September, 2018, Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the State Council on Comprehensively Implementing Budget Performance Management

Finally, in the central-local government relations, the central government must acknowledge its dual role as a "manager" and a "rescuer." Superior to subordinate governments, the central government naturally holds the authority to lead and manage local governments. However, on the other hand, if a local government encounters a problem beyond its capacity, the central government must also be prepared to step in and provide assistance. Only in this way can systemic risks be contained and social confidence stabilized. Whether from the perspective of China's unitary political system or the consensus of the Chinese people, leaving a local government to fend for itself is not a viable option for the central government.

China has just weathered three years of COVID pandemic, and the land finance sector has also suffered a severe setback due to the property market crisis. The challenges posed by these two factors to local governments are unparalleled. Thus, the increase in local government debt risks can be seen as a reasonable response. In such unprecedented circumstances, it will be overly rigid and stubborn for the central government to continue to strictly adhere to the "no bailout" principle.

Conclusion

The conclusion is evident: China's overall government debt size is on a reasonable scale and raises no sustainability concerns. Nevertheless, a structural problem persists, characterized by the share of central government debt being too low and that of local government debt being excessively high.

China's quest for high-quality development hinges on robust GDP growth. Local government debt, an integral element of the capital-oriented, business-style urban management model adopted by local governments, in conjunction with land finance, confers distinct advantages upon the "China model" which features infrastructure investment. This combination serves as a pivotal catalyst propelling the nation's rapid economic advancement.

In a unitary state like China, where the central and local governments share unlimited mutual responsibility, it is incumbent upon the central government to provide timely assistance to local governments when they face challenges. In the face of unprecedented circumstances, such as the three-year pandemic and the property market setback, it becomes even more imperative for the central government to step in and support local government debt to prevent risks from escalating.