Xu Gao: Why curbing investment can backfire in China

The Bank of China International's Chief Economist says income distribution is optimal, but high investment must continue to buy time; otherwise, China faces a demand shortfall and risks decapacity.

Xu Gao, the Chief Economist and Assistant President of Bank of China International Co. Ltd., and an adjunct professor of the National School of Development (NSD) at Peking University, has been featured on The East is Read several times.

In a recent article published in June, Xu Gao argues that in a system where the state and firms retain a hefty share of income and direct those returns to accumulation rather than households, effective demand, not capacity, is the binding constraint on economic growth. To stop savings from congealing as idle balances, investment expands as the residual absorber. China does not consume too little because it invests too much; it invests so much because it consumes too little. On this reading, recent drives to rein in investment and deleverage have tightened the demand bind and heightened the risk of deflation and decapacity.

The optimal cure, says Xu, is to lift the household share of national income by channelling more state-owned capital returns to consumers, thereby anchoring a consumption-led expansion. But reform is slow. Until it advances, Xu contends, China must keep investment working, preferably in infrastructure and housing rather than in new manufacturing capacity, so that demand does not crater. The worst outcome to avoid is a slide into insufficient demand and industrial decapacity; the prudent course is to buy time with continued investment stimulus while preparing the distribution reforms that would place growth on a more sustainable footing.

The article was published in Issue 3, 2025, Globalisation, a bimonthly journal run by the China Centre for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE), a top governmental think tank operating under China’s National Development and Reform Commission. It is also accessible on Xu’s personal WeChat blog.

This is a very long article, so we are just publishing the last bits of it.

供给与需求的辩证法

Xu Gao: The Dialectics of Supply and Demand (Excerpt)

4. Insufficient consumption and demand in China

In Karl Marx’s analysis of economic crises caused by capitalist overproduction, income distribution is the key issue. The central point is that returns on capital, controlled by capitalists, do not flow to consumers (workers). As a result, these returns fail to convert into consumer income or effective demand. This creates a contradiction between expanding production capacity and a relative decline in effective consumption demand, leading to economic crises of overproduction. To resolve this, Marx proposed public ownership, which would allow consumers to share in the ownership of capital. In this way, a greater portion of capital returns would flow to consumers, alleviating the problem of insufficient effective demand.

China is a socialist country where public ownership is the mainstay and diverse forms of ownership develop together. According to the Fourth National Economic Census conducted in 2018, the total assets of Chinese enterprises that year reached 914 trillion yuan. Of this, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) held 475 trillion yuan, accounting for 52 per cent of all corporate assets. In addition, the state, government bodies, and state-affiliated institutions hold substantial assets and natural resources. Public ownership thus occupies a dominant position in China’s overall ownership structure.

This ownership structure has enabled China to marshal resources for major undertakings, both before and after the reform and opening up. As a result, China has transformed from a poor and underdeveloped agrarian country at the founding of the People’s Republic into the world’s leading manufacturing powerhouse. In the course of this transformation, China has moved from an economy of scarcity to one of surplus, with productive capacity shifting from shortfall to excess.

Following the significant transformation of China’s national economy from scarcity to surplus, the allocation of returns from state-owned assets has remained largely inertial. A substantial portion of these returns continues to be directed toward accumulation and investment, while only a limited share flows into the consumer sector. This has intensified the growing imbalance between rapidly expanding supply capacity and relatively weak effective demand in the consumer sector. As a result, the macroeconomy increasingly exhibits signs of insufficient demand and excess supply, phenomena that reflect certain features of overproduction as described by Marx.

Since the mid-1990s, China has faced a persistent shortfall in consumption. Following the outbreak of the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the country entered a prolonged period of deflation from 1998 to 2002, characterised by a state of insufficient demand and industrial decapacity. Although China undertook large-scale decapacity measures during this period, resulting in widespread layoffs and worker displacement, it did not fully eliminate excess production capacity.

China emerged from deflation in 2003, largely due to a surge in external demand following its accession to the WTO in 2001. From 2003 until the Subprime Crisis in 2008, China experienced a phase marked by insufficient consumption, with exports driving aggregate demand. The economy grew rapidly during this period and at times even overheated.

However, the 2008 Subprime Crisis severely constrained the expansion of external demand. In response, China entered a new phase characterised by insufficient consumption, with investments driving aggregate demand. During this period, issues such as declining investment returns and rising domestic debt gradually emerged, significantly weakening the government’s appetite for investment stimulus policies. These dynamics contributed to a sustained slowdown in economic growth.

In recent years, China has faced a growing risk of returning to a state of insufficient demand and industrial decapacity.

The analysis of China’s income distribution structure and the macroeconomic trends over the past 30 years both indicate that insufficient domestic demand, driven by inadequate consumption, has been a persistent issue in recent decades. The active constraint on China’s economic growth has always been demand, rather than supply.

5. Dialectical analysis of insufficient consumption

Both the investment-driven and export-driven aggregate demand reflect insufficient domestic consumption. The distinction lies in the source of demand used to compensate for this shortfall—one relies on domestic investment, while the other depends on external demand. The consequences of insufficient consumption are primarily evident in two key aspects.

One consequence is that when consumption is insufficient, economic development may diverge from its ultimate goal of improving people’s well-being. Since the well-being of the general public (consumers) depends heavily on consumption, a low consumption share in the overall economy creates a disconnect between individual lived experience and GDP growth. As a result, the gains from economic expansion do not fully translate into improvements in public welfare. Despite China’s relatively high GDP growth, many people perceive a disparity between GDP figures and their personal circumstances—an impression largely attributable to the low proportion of consumption in GDP.

The second consequence of insufficient consumption is that economic development lacks endogenous sustainability. In other words, without the support of domestic macroeconomic policies to stimulate investment or external demand to drive growth, economic expansion is likely to stall due to inadequate aggregate demand, even triggering a recession driven by decapacity. In the state of investment-driven aggregate demand, large-scale investment often leads to a steady decline in returns and increasing difficulty in securing future financing. As investment returns fall to very low levels, they may no longer cover financing costs, resulting in a mounting debt burden and heightened concerns over a potential debt crisis. In recent years, China’s rising domestic debt levels have significantly constrained macroeconomic policy.

Even in a state where aggregate demand is driven by external markets, the sustainability of growth remains uncertain, despite relatively limited domestic debt pressures. After all, countries that provide external demand inevitably run long-term trade deficits, which lead to rising external debt in these countries. The expansion of such debt, in turn, constrains the growth of foreign effective demand. Even the United States—the only country able to borrow externally in its own currency—faces mounting domestic concerns about the sustainability of its debt as external liabilities accumulate. These concerns generate pressure to reduce external borrowing and suppress domestic demand, which in turn creates headwinds for China’s export-led growth model.

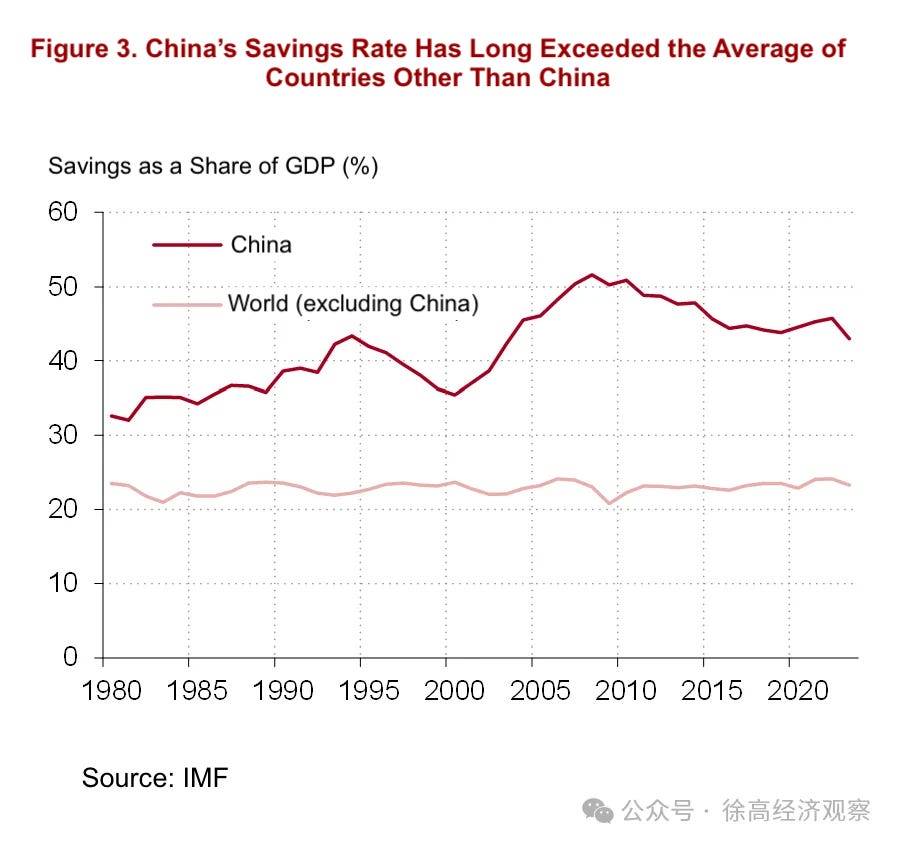

However, it is important to view the situation from a dialectical perspective. While insufficient consumption has the consequences mentioned earlier, it also brings certain benefits. As two sides of the same coin, insufficient consumption is accompanied by a higher proportion of savings and investment in the economy. Over the past four decades, China’s savings rate has remained consistently high, approximately double the global average. This high level of savings and investment has contributed to rapid capital accumulation and economic growth in China.

It can be argued that China’s rapid economic growth since reform and opening up has not only benefited from market-oriented reforms, but has also been driven by a demand structure characterised by low consumption, which has boosted savings and investment. The economic miracle China has achieved over more than four decades since reform and opening up is not simply another case of market reform fueling growth; it is also closely linked to the country’s socialist ownership system and its distinctive demand structure.

It could even be argued that China’s rapid economic development since reform and opening up bears a striking resemblance to the “spirit of capitalism” described by Max Weber over a century ago. In the second chapter of his seminal work The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904), Weber observed: “The earning of more and more money, combined with the strict avoidance of all spontaneous enjoyment of life... Man is dominated by the making of money, by acquisition as the ultimate purpose of his life. Economic acquisition is no longer subordinated to man as the means for the satisfaction of his material needs... (It is) so irrational from the standpoint of purely eudaemonistic self-interest, but which has been and still is one of the most characteristic elements of our capitalistic culture.” Weber’s ideas were later summarised in the phrase “saving for God’s sake.” In the development of capitalist society he described, saving ceased to be a means to secure future consumption and instead became an end in itself—saving for saving’s sake. This shift propelled capitalist societies through periods of rapid capital accumulation and economic expansion.

Of course, as discussed earlier, if the expansion of supply capacity driven by high savings and investment is not matched by effective demand, the economy will inevitably stagnate. However, with a thorough understanding of how the macroeconomy functions under insufficient consumption, it becomes clear that as long as domestic macroeconomic policies are properly aligned, China’s growth model, despite being consumption-deficient, is sustainable. There is no need to be pessimistic about its future prospects.

As previously discussed, the investment-driven growth model does lead to declining investment returns and rising domestic debt. However, this does not necessarily render the model unsustainable. China’s low investment returns and high debt levels are, in fact, a compensation for its high savings rate. In other words, insufficient consumption is not the result of excessive investment; rather, high levels of investment are required because consumption is insufficient. Put differently, the scale of investment must be large enough to absorb the country’s substantial savings. Without adequate investment to channel these savings into productive use, purchasing power would remain idle in the form of unutilised savings, thereby worsening the problem of weak effective demand.

In this context, as long as China’s high savings rate persists, substantial investment will be needed to absorb it. Moreover, supported by the high savings rate, investment will continue to be sustained by domestic savings even as returns decline and debt levels rise. There will be no risk of a funding shortfall or a breakdown in investment activity. As long as high savings remain available as a source of capital, investment can proceed even if returns fall to very low levels because the flow of savings will continue to support it.

In fact, although China’s domestic debt has reached a relatively high level, data from its International Investment Position (IIP) reveals that by the end of 2024, the country’s net external assets (external financial assets minus liabilities) had increased to $3.3 trillion. For those concerned about the scale of China’s domestic debt, it is important to keep in mind that China have also lent over $3 trillion to foreign countries. Given this, there is little reason to be overly concerned about the risk of a domestic debt crisis.

Some analysts contend that China’s diminishing returns on investment reflect a waste of resources. This view, however, captures only part of the picture. In scenarios of overinvestment, the most efficient approach is often to pause capital expenditure and redirect funds originally allocated for investment toward consumers, thereby boosting consumption. This requires redistributing income from investors (including state-owned enterprises) to households. Yet, China currently lacks a practical framework for such income transfers.

In other words, reducing investment does not automatically translate into higher consumer income or spending, but rather exacerbates the issue of insufficient effective demand, potentially triggering a decapacity situation of business closures and worker layoffs. Such outcomes would result in even greater resource waste. In this context, China’s investment-led economic growth model remains the constrained optimum, given the stagnant share of consumer income and weak external demand.

Currently, there remains a considerable lack of dialectical and comprehensive understanding regarding China’s insufficient consumption. Many focus solely on its negative aspects, overlooking the competitive advantages it offers for boosting productivity. They also fail to see that, with appropriate policy support, this model can in fact be sustained.

As a result, in recent years, China’s macroeconomic policies have often focused on curbing investment and controlling debt, which has further aggravated the problem of insufficient effective demand. Given the current international environment, marked by escalating U.S. trade protectionism, failure to adjust policy and actively stimulate investment would undermine China’s economic growth and increase the risk of a slide into insufficient demand and industrial decapacity.

6. China’s policy choices

In economic development, supply and demand are like the two legs on which an economy stands—both are essential, and either can become an active constraint on growth. Determining whether the bottleneck lies on the supply side or the demand side requires case-specific analysis, not a one-size-fits-all approach.

When applying mainstream Western macroeconomic theories to China, it is essential to examine their underlying assumptions and assess their relevance to China’s specific context. As noted earlier, Say’s Law, a key implicit premise in the dominant Western macroeconomic paradigm, does not hold in China. As a result, China’s long-term growth is constrained more by demand-side factors than by the supply-side issues emphasised in Western macroeconomic theories. Accordingly, China should prioritise demand-side policies to maintain stable economic growth.

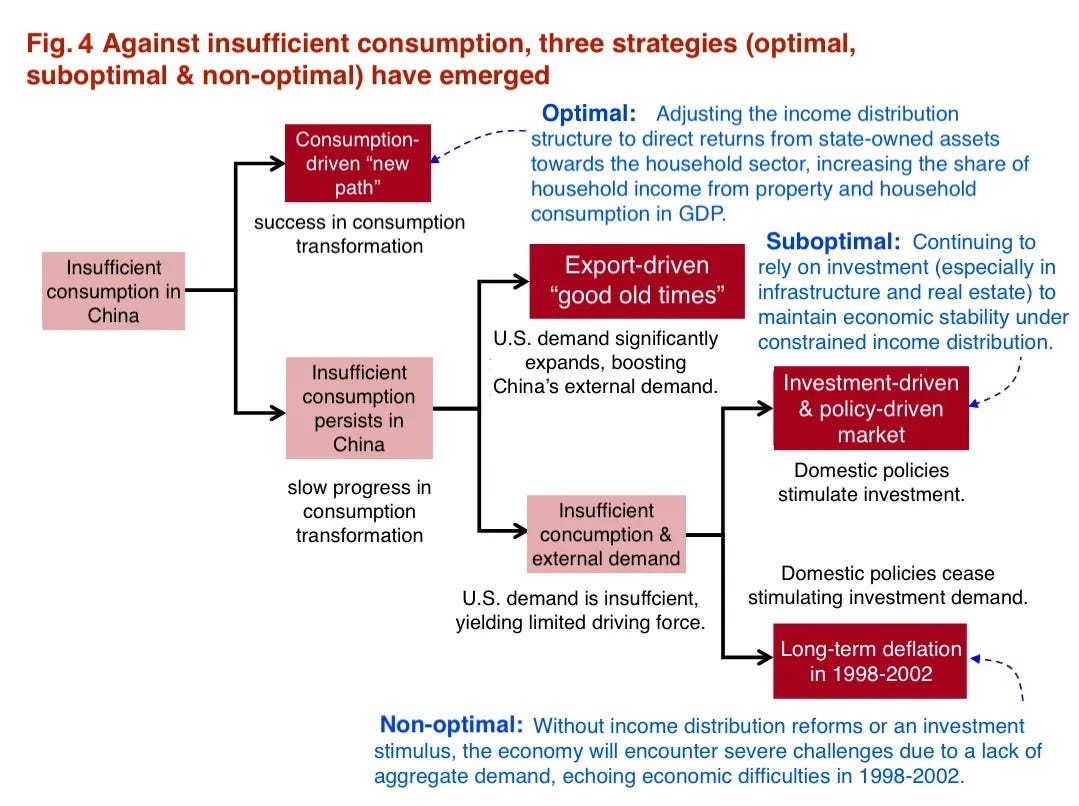

I see three possible policy strategies for China: optimal, sub-optimal, and non-optimal. The optimal strategy is to restructure income distribution by increasing the share of household income in GDP. Above all, China should redirect a larger portion of state-owned capital returns to consumers. Traditionally, these returns have been used primarily for capital accumulation and investment, a strategy suited to the era of resource scarcity. However, as economic conditions evolve, a growing share of these returns should be allocated to boosting public income and consumption. This shift would guide China onto a path of consumption-driven transformation, characterised by more balanced supply and demand, more endogenous and sustainable growth, and more benefits of growth directed to ordinary citizens. My 2024 article offered concrete policy recommendations for putting this optimal strategy into practice [which The East is Read translated and published as seen below.]

In the absence of significant progress in income distribution reform, key to China’s shift toward consumption-driven growth, the country must rely on domestic investment and external demand as its main sources of effective demand. However, external demand lies beyond China’s control and cannot be a dependable solution to domestic demand shortfalls. When consumption is insufficient, the reliable approach is to stimulate investment to generate effective demand.

China’s investment is concentrated in three sectors: manufacturing, infrastructure, and real estate. Investment in manufacturing quickly translates into incremental production capacity, which risks worsening domestic overcapacity. Therefore, policy should emphasise infrastructure and real estate investments, which do not significantly expand capacity, as key levers for stabilising growth. This approach supports economic stability while maintaining China’s supply-side advantages stemming from insufficient consumption. This represents the sub-optimal strategy.

However, if income distribution reform stalls and effective investment stimulus is lacking, China will inevitably drift toward the worst-case scenario: insufficient demand and industrial decapacity. Contrary to some naïve assumptions, the market will not automatically adjust through simple clearance mechanisms. This is because the root of China’s demand-side imbalance lies in its income distribution system, which cannot be corrected merely by an economic slowdown. Furthermore, decapacity would erode China’s international supply-side competitiveness, undermining economic stability and even risking social unrest. This is the non-optimal strategy, one that prudent policymakers must strive to avoid. (Fig. 4)

In sum, drawing on historical debates over effective demand and China’s unique national conditions, this analysis has explored the roles of both supply and demand in the country’s economic development. By moving beyond the limitations of mainstream Western macroeconomic paradigms and adopting a dialectical perspective on the respective roles of supply and demand, it becomes possible to identify key bottlenecks in the Chinese economy, formulate a coherent policy response, and make the right decisions. This approach will help keep the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation on course. Among the three strategies, China should adopt the sub-optimal path to gain time, actively prepare for the optimal strategy, and firmly avoid the non-optimal one.