Part II of Xu Gao: Chinese economy at a forking path, leading to three possible futures

Three scenarios: income structure reforms are the optimal path, investment stimulus is a necessary evil, and the perils of the investment curtailment must be avoided to mitigate deflation risks.

On March 13, 2024, the National School of Development (NSD), Peking University, in collaboration with Baidu Economic & Financial News, held the 68th session of the China Economic Observation Report event and launched the 30th-anniversary celebration of the NSD.

Several leading Chinese economists participated in the session, offering their assessments of China's economic landscape and their visions for future development, especially against the just-concluded "Two Sessions." The East is Read has already published a speech by Lu Feng from the event. Another speech by Justin Yifu LIN has also been published by Pekingnology, a sister newsletter of The East is Read.

Today's The East is Read will continue featuring Xu Gao, having published the first half of his speech at the event. Xu Gao is the Chief Economist and Assistant President of Bank of China International Co. Ltd., leading the research department and sales and trading department of the company. He is also an adjunct professor of the NSD at Peking University.

Xu identifies the key challenge facing the Chinese economy as insufficient domestic consumption, which is a result of the imbalance in income distribution between the corporate and household sectors.

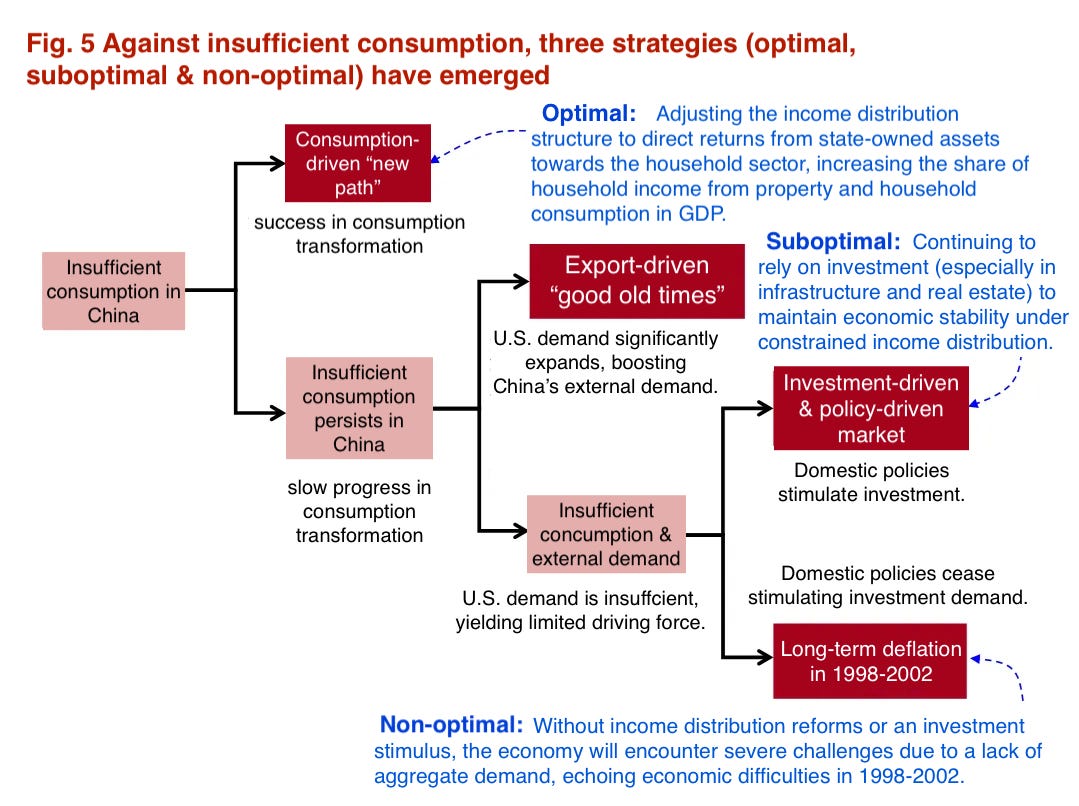

To address this, Xu charts three scenarios based on three potential policy responses from Beijing:

The best scenario sees success income distribution reforms, such as increasing the public's decision-making power over SOEs and creating a market mechanism that dynamically adjusts income distribution between households and corporations. This would increase the proportion of household income in GDP, thereby stimulating consumption. This path is considered the most favorable.

An alternative scenario adheres to the traditional investment-led growth model, which focuses on stimulating investment to drive demand and stabilize growth. While not optimal, this model has been crucial to China's rapid economic development and should not be dismissed outright.

The worst scenario is one in which investment stimuli are restricted or investments are curtailed. Such actions are unequivocally cautioned against, as they could lead to prolonged deflation and significant risks to economic growth and employment.

The original video recording of the speech is available on the NSD's official WeChat blog. Please note the following translation is derived from Xu's personal transcript of his speech, in which he included additional details and structured the content more systematically. The Chinese version can be found on Xu's personal WeChat blog 徐高经济观察 Xu Gao Economic Observation and was also cross-posted to the NSD's official WeChat blog.

The optimal, suboptimal, and non-optimal strategies for the Chinese economy

Based on the above analysis, it is clear that the crucial bottleneck in the Chinese economy is that in the secondary income distribution, the transfer of income from the corporate to the household sector lacks responsiveness to ROI. This deficiency disrupts the market's natural income redistribution mechanisms between these sectors, leading to a notably low ratio of household income to GDP. This means China is faced with insufficient consumption, which then results in insufficient demand, limiting long-term economic growth.

Therefore, as I previously emphasized, the central challenge to China's economic growth is rooted in demand, not supply. Approaching the slowdown through a supply-side lens, like attributing it solely to the aging population, is misguided.

Aggregate economic demand comprises consumption, investment, and external demand (exports). While consumption and investment are domestically influenced, external demand is largely subject to foreign actors. To address insufficient consumption in China, three possible policy responses have emerged (Fig. 5):

The "optimal strategy" involves implementing income distribution reforms favoring households to promote consumption transformation.

The "suboptimal strategy" aims to stabilize growth by stimulating investment when income distribution reforms progress slowly.

The "non-optimal strategy" suggests halting investment stimulus (or even curtailing investment) until substantial progress is achieved in income distribution reform.

The "optimal strategy" focuses on income distribution reforms through the implementation of a "Universal Shareholding Scheme for SOE Stocks," which aims to increase the share of household income in the GDP, thus enhancing consumption's contribution to the economy and steering towards consumption transformation.

To elevate the share of consumption within China's GDP, increasing household income is an essential first step. Without a substantial rise in household income, attempts to boost consumption may not achieve their intended impact. As the above analysis underscores, income distribution reforms in China should not just enhance household incomes but also, more importantly, create a market mechanism that dynamically adjusts the distribution of income between the household and corporate sectors based on the ROI, which must act as a critical price signal.

Simply boosting household income is not enough. It is pivotal to grant the public decision-making power over operational, investment, and dividend decisions in enterprises. Large SOEs in China provide a unique opportunity to pursue this strategy. Since these enterprises undoubtedly belong to the public, the logical progression is to facilitate the public's direct exercise of their ownership rights. This move aims to make state assets tangible, accessible, and beneficial to the people, thus directly bolstering consumption. This strategy is further discussed in the article "Why SOE stocks should be distributed among all citizens" [which has been translated & published by The East is Read.]

Implementing this scheme will aid in income distribution reforms that favor the household sector, which is fundamental for addressing China’s persistent challenge of insufficient domestic demand, ensuring sustainable growth, and guaranteeing that economic advancements genuinely improve people's welfare, thus reflecting the essence of high-quality development.

No doubt, reforming income distribution is a gradual process. Until China fully transitions to a consumption-led economy, it must continue to depend on exports or investment to spur demand and sustain stable growth. However, control over external demand is outside China's complete jurisdiction. Given the nation's vast economic scale, it is increasingly difficult for foreign economies to boost demand from China. Moreover, the global rise in protectionism is erecting barriers to Chinese exports, making reliance on external demand for economic prosperity, as seen before 2008, untenable for China.

In the absence of significant progress in income distribution reform and with weak external demand, the key to the stability of China's economic growth lies in the vigor of domestic investment. This leads to the "suboptimal" and "non-optimal" strategies.

The "suboptimal strategy" suggests continuing to fuel investment to drive demand and stabilize growth, given the constraints of sluggish consumption (due to limited progress in income distribution reforms). Although this approach is not ideal—the "optimal strategy" would be superior—it represents the "constrained optimum" within the bounds of the existing income distribution structure. In economic terms, this strategy is deemed "suboptimal."

Nonetheless, incessantly boosting investment to generate demand has its downsides. For instance, extensive infrastructure investments have saddled local governments in China with substantial debts. Also, the high leverage of Chinese real estate developers, coupled with an unsustainable focus on leverage and turnover among some of them, introduces risks. Hence, this investment-led growth model is prone to criticism. In recent years, China has approached investment stimulation with increasing caution and has even enacted policies to reduce leverage in the real estate sector, which has notably dampened real estate investment. Although these steps seem reasonable, they represent the "non-optimal strategy" — more disadvantages than advantages and inferior to the "suboptimal strategy."

The "non-optimal strategy," which involves halting investment stimulation or even curtailing investment in the absence of substantial progress in income distribution reforms, could plunge the Chinese economy into extended deflation, widespread business shutdowns, and unemployment, akin to what occurred from 1998 to 2002.

As discussed, the structural imbalance in the Chinese economy, characterized by insufficient consumption and excessive investment, originates from the disproportionately low share of household income within the income distribution structure. This imbalance will not self-correct through investment suppression or economic downturn. Contrary to some naive beliefs, curbing investment will not naturally equilibrate the economic structure but will instead deepen the demand shortfall and induce a passive contraction of the supply side (business shutdowns and job losses). This limited perspective, which overlooks the broader macroeconomic context, has been the primary cause of the "fallacy of composition" in China's macroeconomic policies in recent years.

Embracing a dialectical perspective on the "suboptimal strategy"

The "suboptimal strategy" is often critiqued as the "old path" for its reliance on investment-driven growth. However, before blindly dismissing the "suboptimal strategy," one crucial point must be understood: China ascended to the world's second-largest economy and substantially increased its population's income levels thanks to the so-called "old path" employed in recent decades. It's crucial to recognize that every strategy has its advantages and disadvantages, which must be weighed dialectically.

Indeed, the investment-centric approach of the "suboptimal strategy" has downsides. It can lead to overinvestment and inefficiencies, where economic growth does not fully translate into enhanced welfare for the people. This approach risks creating structural imbalances in the economy, insufficient demand, and a lack of sustainability.

However, the benefits of the "suboptimal strategy" should not be overlooked. Excessive savings and overinvestment can accelerate capital accumulation, fostering faster economic growth in China. Crucially, this strategy affords China a competitive edge in terms of lower capital costs.

Capital cost represents the expected return demanded by capital owners. Higher demanded returns make capital more expensive, while lower demanded returns make capital more affordable. As discussed earlier, a key factor behind China's insufficient consumption is the absence of a mechanism where consumption and investment are adjusted by the ROI's price signal. When the ROI dips, investment levels in China do not necessarily decrease in tandem. This indicates a low sensitivity of China's investment to its ROI; investments continue even when returns are low. In contrast, more market-driven economies find it challenging to sustain high investment levels under low ROI.

When entities with differing sensitivities to ROI compete within the same market, those less responsive to such rates often prevail. This is because entities highly sensitive to ROI cannot match the level of investment intensity demonstrated by those with lower sensitivity. China has effectively capitalized on this competitive advantage, thanks to its lower capital costs, across a range of industries. Once China crosses the technological threshold in a specific sector and gains market recognition for its products, it employs massive investments, regardless of return rates, to dominate the industry, which ultimately leads to overcapacity. The automobile sector is a current illustration of this pattern.

Contemporary mainstream Western economics typically views savings and investment not as the end but as the means to greater future consumption. It is believed that savings and investment are mechanisms for deferring current consumption to the future. If the return on savings/investment is too low, it becomes unprofitable to shift consumption from the present to the future, and therefore, savings/investment should be reduced. This is the fundamental reason why the scale of savings/investment) should be responsive to returns.

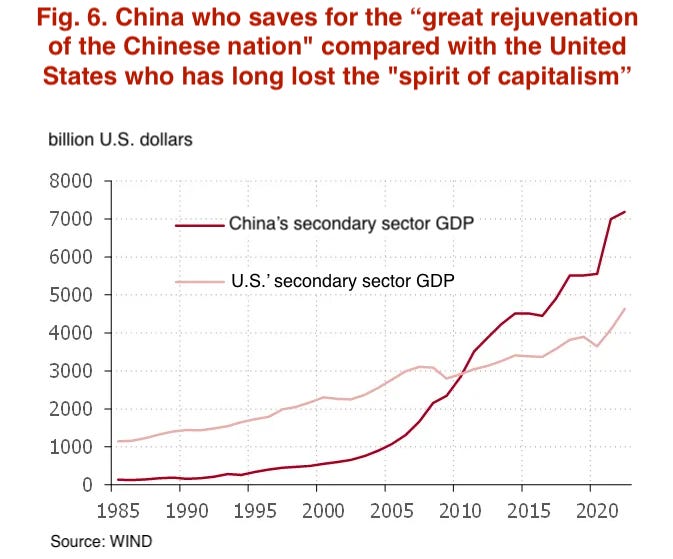

Yet, China's saving behavior distinctly deviates from this doctrine. Income flowing to China's corporate sector during primary distribution, due to the lack of a mechanism for redistributing dividends to residents, is rigidly converted into savings and investments. In this scenario, the purpose of savings extends beyond merely facilitating future consumption. Instead, savings serve the dual purpose of strengthening enterprises on a microeconomic level and bolstering the national economy on a macroeconomic scale. It is possible to go so far as to say that China is saving for the "great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation." The rigidity of savings behavior contradicts contemporary Western mainstream economics that regards savings as a mere "means," yet it is one of China's unique national conditions.

This perspective on savings mirrors the "spirit of capitalism" in Western academia. Max Weber wrote in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, "…the earning of more and more money, combined with the strict avoidance of all spontaneous enjoyment of life…Man is dominated by the making of money, by acquisition as the ultimate purpose of his life. Economic acquisition is no longer subordinated to man as the means for the satisfaction of his material needs…so irrational from a naive point of view, is evidently as definitely a leading principle of capitalism…"

Weber's analysis positioned "the making of money" as the objective in itself, rather than a means to enhance the "enjoyment of life" (consumption). Subsequent economists have interpreted Weber's notion of the capitalist ethos as saving in devotion to God rather than for future consumption. Influenced by this ethos, capitalist societies witnessed phases of swift capital accumulation and economic expansion. "The Spirit of Capitalism and Stock Prices" by Chen Zhiwu and Gurdip Bakshi, published in the American Economic Review in 1996, delves into how this spirit of capitalism influences macroeconomic and financial market dynamics.

Certainly, socialism with Chinese characteristics diverges fundamentally from capitalism. China promotes effective integration of the market and the government to achieve common prosperity, adhering to the principle of common prosperity where some people are allowed to create wealth as a first step to bringing prosperity for all. Nonetheless, China's approach to excessive savings bears resemblance to the spirit of capitalism described by Weber in its end for rapid capital accumulation.

Contemporary Western capitalist economies have gradually moved away from this "spirit of capitalism," focusing more on consumption and personal gratification. This shift has led to a decline in their capital accumulation and economic growth rates, with the United States serving as a prime example. In contrast, China, motivated by the "great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation," will naturally surpass the Western countries that have lost the "spirit of capitalism."

Based on current exchange rates, China's GDP is only about 70% of the United States'. However, focusing solely on the secondary sector (industry and construction), China's GDP in this area is already 1.5 times that of the United States, clearly surpassing it. This achievement in production capacity is attributable to China's investment-led growth strategy. (Fig. 6)

In various industries, the "suboptimal strategy" manifests as China's strong competitiveness. Once China crosses the technological threshold in a specific sector and gains market recognition for its products, its significant edge in capital costs becomes apparent, swiftly transforming the competitive dynamics and establishing China as a leading, even dominant, player in the sector. Since the reform and opening-up policy, this phenomenon has been observed across numerous industries, with the automobile sector as a current illustration in recent years.

Since 2020, capitalizing on the shift towards new energy, China's automobile industry has achieved substantial progress, with its vehicles and brands receiving widespread market recognition. The result — China has become the world's largest automobile exporter. China's monthly vehicle exports, which were below 100,000 in early 2020, have now surged to almost 500,000. This remarkable advancement is credited not only to the strategic benefits of transitioning to new energy but also to China's impressive competitiveness rooted in its capital cost advantage.

Hence, in evaluating China's investment-driven "old path" or the alternative "suboptimal strategy," a balanced perspective is essential. It's important to avoid outright dismissal and recognize not just the shortcomings but also the strengths of these strategies.

The Chinese economy must avoid the "non-optimal strategy"

Despite remarkable achievements in the automobile industry post-2021, the broader Chinese economy has faced intensifying challenges, primarily triggered by the real estate sector falling into a vicious cycle under tightening financing policies.

Following the implementation of more stringent financing policies in 2021, the scale of funds for property investment in China has halved, doubling down on the credit risk for property developers. This situation has led to a reluctant stance among potential homebuyers, wary of the risks associated with unfinished projects; financial institutions are reluctant to extend credit to developers due to fears of accruing bad debt. This reluctance from buyers and lenders alike has placed additional financial strain on developers, exacerbating credit risks and ensnaring the property sector in a difficult-to-break cycle of challenges.

At the "Outlook for H2 Economy and Real Estate Transformation" forum, hosted by Peking University's NSD on July 12, 2022, I thoroughly examined these challenges within the real estate sector and recommended three policy measures: easing the financing restrictions on real estate, creating a short-term relief fund to mitigate developers' credit risks, and devising a land supply system with higher price elasticity. Regrettably, the supporting measures taken thus far have not effectively tackled the fundamental issue of credit risk for developers, leaving the real estate market in a prolonged state of stagnation.

Years ago, China's decision to tighten financing for the property sector was driven not only by concerns over the high-leverage business models of some developers but more importantly a misinterpretation or underestimation of the "suboptimal strategy." Some believed that promoting deleveraging and curbing investment would naturally restore economic equilibrium. However, as previously analyzed, this view overlooks the fundamental constraint of China's insufficient consumption, a result of its income distribution structure, rendering such assumptions naive and overly optimistic.

Before substantial progress is made in income distribution reform to increase household income, adopting the suboptimal strategy—utilizing investment, particularly in infrastructure and real estate, to generate stable growth—is not the "optimal" choice for China's economy, but rather a "suboptimal" one under income distribution constraints. Under the constraint of income distribution, it's challenging for consumption to become a powerful engine of demand-side economic growth in China. At this juncture, suppressing investment would be counterproductive. Some naive individuals might believe that by curbing investment, the economic structure will automatically optimize. However, the reality is that such actions would likely plunge China back into a prolonged deflationary period similar to that experienced from 1998 to 2002, imposing significant pressure and risks on economic growth and employment.

Before meaningful advances in income distribution reform are realized to enhance household income, pursuing the "suboptimal strategy"—particularly focusing on infrastructure and real estate to foster stable growth—represents a "suboptimal" approach within the confines of income distribution challenges for China's economy. Given these constraints, transforming consumption into a robust driver of demand-side economic growth in China remains a daunting task. At this critical point, restricting investment would be suicidal. Contrary to some naive beliefs that limiting investment will automatically refine the economic structure, it could thrust China into an extended period of deflation similar to the 1998-2002 era, exerting considerable strain on economic growth and employment.

Thus, it is imperative for China to steer clear of the "non-optimal strategy" by maintaining stable investment levels to secure economic growth and reinforce its stance in the China-U.S. major power rivalry.

In the Central Economic Work Conference in December 2023, top Party leaders explicitly called for policies to "establish the new before abolishing the old." The achievements of China's automobile industry in recent years highlight China's success in nurturing new avenues for growth and fostering new productive forces. In terms of "establishment," China's endeavors have been significant and noteworthy. Nevertheless, the nation has overextended in dismantling traditional growth drivers, which are pivotal to its economic foundation, with some of the measures both lacking solid theoretical and practical grounding.

As such, since last year, I have been advocating for a recalibration of policy orientation and the formulation of policies that align more closely with China's actual conditions. Additionally, it's essential to dispel misconceptions such as the idea that leveraged growth is unsustainable or that "debt is poison," to prevent the economy from shifting towards the "non-optimal strategy."

Although the Chinese economy is currently facing downward pressure, there remains considerable scope for policy adjustment, and the nation is well-equipped to sustain stable economic growth. Moving forward, China must resolutely avoid the "non-optimal strategy," employ the "suboptimal strategy" as a temporary solution, and ultimately, address the structural issues of its economy with the "optimal strategy" to embody the true nature of high-quality development.