Transcript: Zhou Yongmei on why “good governance” may not be a prerequisite for development

Peking University scholar and longtime World Bank official explains why some economies grow before they tidy up—and what that implies for reformers.

Zhou Yongmei is Professor of Practice in Institutional Development at the Institute of South–South Cooperation and Development (ISSCAD) and the National School of Development (NSD), Peking University, a role she has held since 2020. She received her PhD in economics from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1999, specialising in new institutional and development economics. From 1999 to 2020, she worked at the World Bank, advising leaders in Africa and South Asia, managing the Fragility, Conflict and Violence Group, and co-directing the 2017 World Development Report. Based in Jakarta from 2017 to 2020, she led the Bank’s largest country programme on economics, finance and institutions, overseeing US$1 billion in projects and US$12 million in technical assistance across fiscal policy, public financial management, local governance, financial inclusion and digital development.

Speaking at the Global South Network meeting in Jakarta on 10–12 June, Zhou argues, on cross-country evidence, that tight control of corruption appears close to necessary for graduating to high-income status, though not for the step from low to middle income. She calls for a shift from checklist virtue—treating “good governance” as a box-ticking imperative—to measurable capacities. The aim is not to abandon democratic values, but to ask which institutional muscles actually move an economy, when, and by how much. Her empirical work gives firmer footing to the broader, often grand, discussions of “diversity in governance models”.

Zhou delivered her remarks in English and generously shared with us her slides and the voice recording used for transcription. A Chinese translation has been published by Guancha.cn, a domestic media portal in China, and is also available on the NSD’s official WeChat blog.

—Yuxuan Jia

周咏梅:“善治”真的是全球南方国家治理的第一要务吗?

Zhou Yongmei: Is “Good Governance” Really the Top Priority for Countries in the Global South?

Thank you very much. What I’m going to speak about is a question of whether good governance is a precondition for development, and I’m hoping that this will be a little bit controversial. I have been in the World Bank for more than 20 years doing institution-building and governance reform work in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. So in a way, it’s a little suicidal to come here and now ask this question. But now I’m in the academia, so I am free.

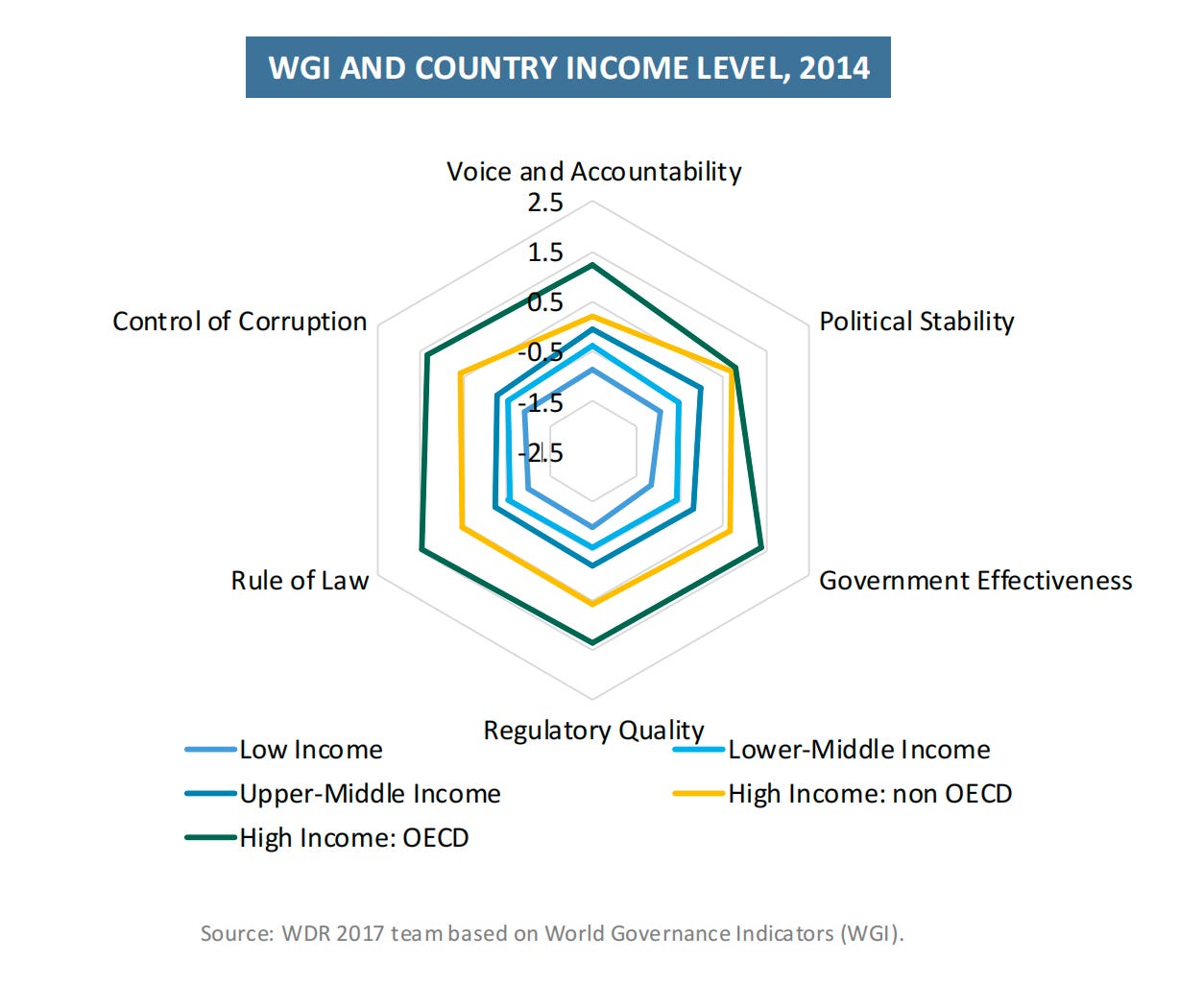

Now, why ask this question? It’s almost embarrassing to say we don’t care about governance. There are too many cases where poor governance impedes development. And in my own work, for example, at the aggregate level, if we look at the six standard indicators from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), from voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, control of corruption.

Frankly, it’s hard to debate that these are not necessary, not good to have. Even if you look at the different income groups, there does seem to be a very strong association at the group average level. As countries grow richer, their governance quality, measured by these six different dimensions, does grow accordingly. The question, of course, is whether there is any causality. What is egg, what is chicken, right? Whether institutions are developing as development happens or the other way around.

When I worked in Sierra Leone right after the Civil War, we do public expenditure tracking, and there is an enormous amount of leakage of public resources showing in our study. For example, if you trace the public expenditure related to essential drugs, only less than 10% of essential drugs can be accounted for at the district level, and less than 5% can be accounted for at the peripheral clinical level. That’s certainly poor governance, and that certainly is bad for development. The same thing is happening in the education sector. It’s happening in the agriculture sector. So this is a strong case where we definitely have a very strong motivation to improve the way public authority is exercised in managing these very important developmental programmes.

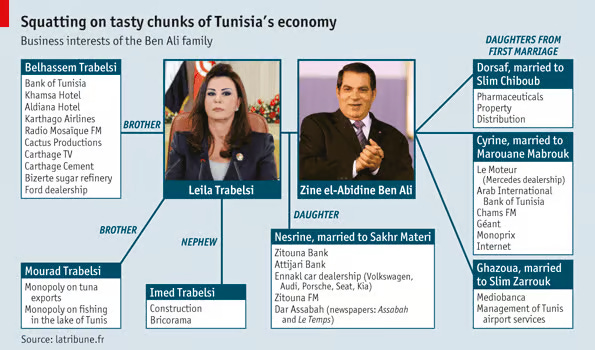

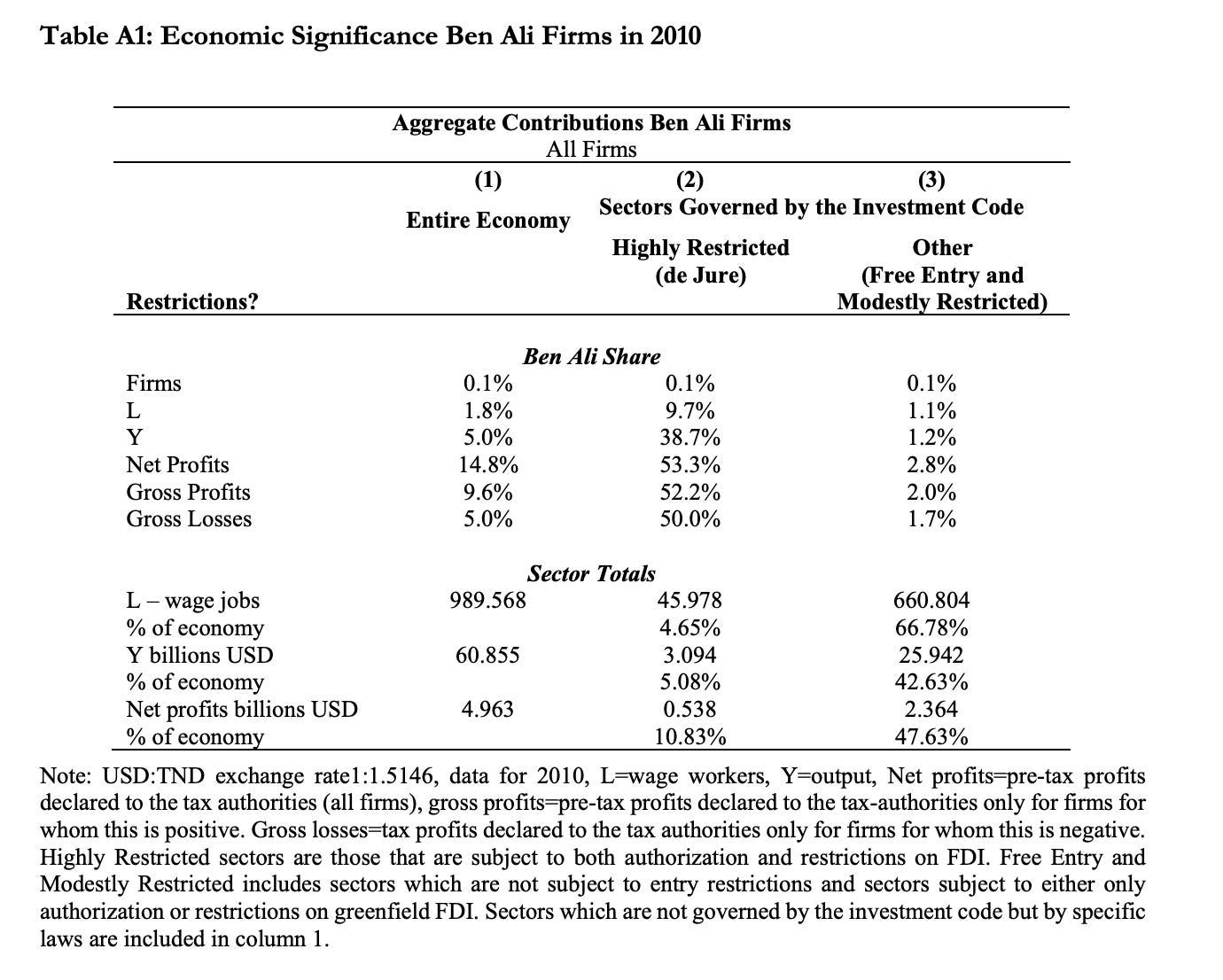

Now, Tunisia, it’s a different story. After Ben Ali’s government fell, our colleagues in the research department of the World Bank had ownership of the entire firm’s data during Ben Ali’s time and saw that the entire economy, the tasty chunks of it, is really in the ownership of Ben Ali and his wife and their children and their relatives. And if you look at the statistics, even though they only own one out of 1,000 companies and hire less than two per cent of labour and produce less than 5% of output in the entire economy, they do have nearly 15% of net profit.

Why? How does that happen? It’s because they are sitting in the highly restricted sectors, you know, those sectors that, due to the investment code, require all kinds of licensing and regulation. So the entry is difficult. And this particular family, due to its own political power, occupies this juicy chunk of the economy. And that is certainly poor governance and poor development, right? So again, in this case, I don’t think we’ll debate whether this requires reform. And now, of course, Ben Ali’s government fell and Tunisia has changed into a democratic regime.

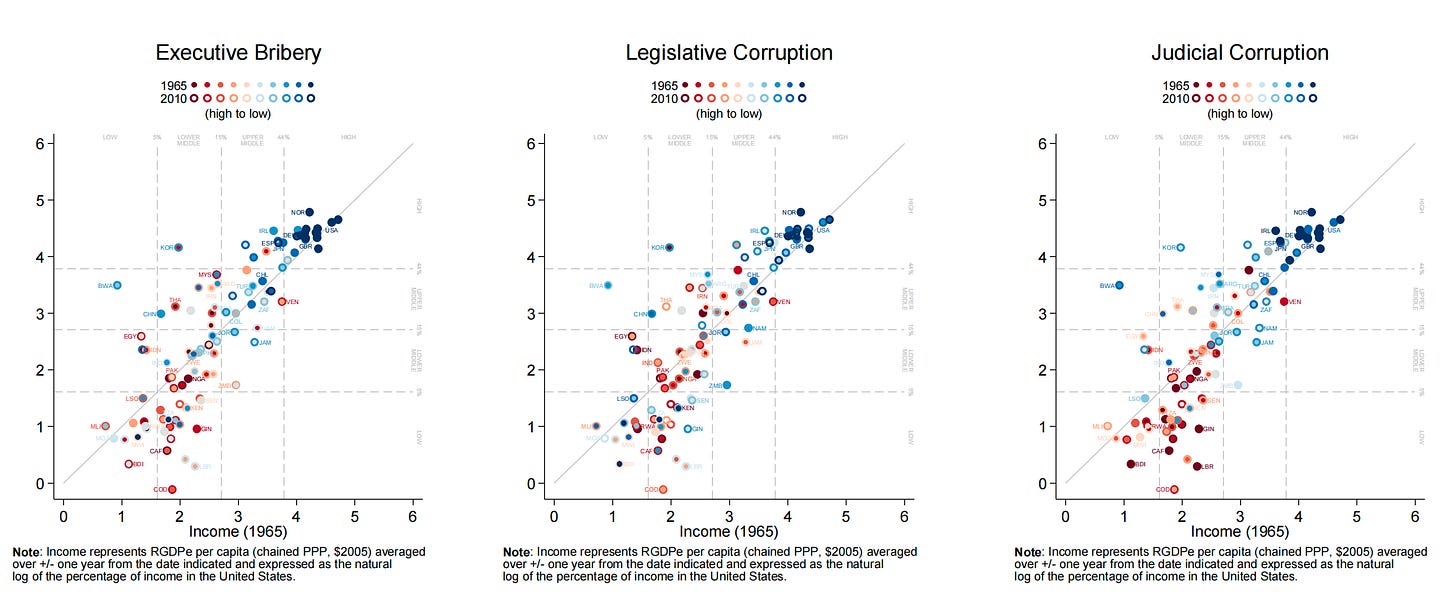

What makes it complicated, though, is if we look at the Global South. At the world level, if I map out the development data between 1965 and 2010. I have updated data, but don’t have all these fancy coloured dots, so I couldn’t present you. But their story is the same.

If we look at the convergence story. In this map, what this is showing is among all the countries, we want to see whether the poor countries relative to a benchmark country, like the U.S., are catching up or not in the post-war 50 years or 45 years’ time.

So, on the upper right corner, these dark blue, these are the developed countries that are relatively in a similar relative position compared to the U.S. But there are many developing countries that have caught up. So their relative position is way above the 45-degree line, meaning the ratio of their economy as a ratio of the US benchmark economy is much larger in 2010 compared to 1965. So these upper-level, if you see the countries way above the 45-degree line, they will have Singapore, South Korea, China, and Botswana, all the countries we would say developed really fast. And then you have all these countries way below the 45-degree line. These are Malawi, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They are actually relatively even worse off today compared to 1965, when a benchmark edwith the developed countries.

So this greater divergence story among the Global South is an extremely important story to unpack. So I mapped out the corruption data for these countries, and blue means good, red means bad. And you can see roughly, countries that are obviously developed and then seem to have little corruption, whether in the executive or judiciary or legislative. These are some of the OECD countries, the familiar stories.

But in the Global South, you have a lot of messy reds, even among those who are fast-growing miracle economies, way above the 45-degree line. I think Indonesia in Suharto’s time was an example or the Chinese example or the Vietnam. All of us, actually, when we were developing really rapidly, corruption was actually also really bad.

Now, in many ways, this is a not-so-comfortable message for governance people, right? Development can happen in messy places. But you know, as my advisor, Pranab Bardhan—he is Indian—says, but Yongmei, Chinese corruption is different from Indian corruption. In China, you bribe one person, he gets things done; in India, you have to bribe nine people. Every single one of them can veto, right? That sort of detail as to the nature of corruption; how decentralised it is, how damaging it is for development—this is never going to be measured by this kind of macro national level data. I think for research, we need to do much more micro-level study. And Mushtaq Khan in London, his group is very sophisticated to understand what kind of corruption is most damaging. And that’s where developing countries with resource constraints can focus their effort on.

So I think the reason I want to bring this issue to GSM is because we are all in that messy middle. We are all trying to figure it out with resource constraints. Can we have richer research programmes that really compare the type of poor governance and the puzzle why poor governance settings still can have development? That’s a research agenda that’s really worth exploring. So that’s one point. Now, the other reason why we need to figure out why GSM needs to talk about this controversial topic to be a little politically incorrect that, perhaps, good governance or perfect governance is not the precondition. It’s not to accept that poor governance is morally correct or is universally non-damaging to development, especially the Sierra Leone case, the Tunisian case. It is certainly very damaging in some cases. But it’s really to help us prioritise.

For example, in the bottom left, all the red, a lot of them are stuck in this trap of a repeated cycle of conflict and violence. Their institutional priorities, we have summarised, are these four sets of priorities:

Sanction and deterrence institutions

Power-sharing institutions

Redistributive institutions

Dispute resolution institutions

I’ll give you an example of East Timor. East Timor said after the civil war or after independence, we do three things; only one is accepted by the international community as good practice, which is to manage their oil according to the Norway model, the sovereign wealth fund. And they really literally went study tour, they come back and you copy. And that’s sort of accepted by the West, right? That’s according to the Norway model. But they did two other things that they consider extremely important for peace-building. One is to have a district fund for all the local governments to be busy to do development. This development community did not like it because they were very much worried about corruption at the local level, and this patronage through this programme. And they also did another thing development community did not like, which is to pay veterans, pay them off so they could put down the gun and then I guess, you know, not engaging in violence. And that’s also a very expensive programme.

And so, from an efficiency point of view, there is reason for the development community to object to two high-priority programmes that East Timor considers essential for their peace-building process. So I think that there is really this debate as to what is most important at what stage of development. And for a post-conflict violence-affected place, perhaps certain tradeoffs must be accepted. And I think that’s an honest conversation that the GSM community can engage in.

The other that I’m not showing here we have in the World Development Report 2017 on Governance and Law, which I directed. We had also taken a look at the institutional changes that are different between those who have escaped low low-income trap to the middle-income category versus those who are stuck. And then we also compare those who escape middle income to high income and those who are stuck. And what’s interesting is that corruption is actually a must-do when you want to get into high income, but it’s not a must-do when you want to escape low income into middle income. But bureaucracy already is significantly improved in those countries that escape from low income to middle income.

I mean, this is not very rigorous, but you know, we were doing the comparison of these two groups. I think that’s also worth plugging away at, to more rigorous research. I want to conclude by saying that hopefully, with the GSM support, we can change the narrative from the good governance agenda to an agenda of incrementally improved institutions.

And I had proposed in the WDR2017 focusing on three institutional functions, which are for building credible commitment, building coordination capacity, and building capacity to generate voluntary cooperation from all stakeholders. And these three Cs, to us, are functional improvements that we can measure in particular policy arenas over time. So, these are hopefully a different way of talking about the governance reform agenda.

I think the Vietnamese colleague Huang talked about this morning, the lack of a universal value system. I personally don’t think we are objecting to democratic values. Personally, I should think democratic values are extremely important and hopefully universal. But the forms of institutions might be very diverse. It doesn’t have to be today’s failed electoral democracies as the form of realising that value. And we need to find out different ways to achieve inclusion, voice, accountability, and transparency through diverse practices, which we can then research and compare. Thank you very much.

Nice, heartily agree with the closing paragraph. No single “right” democratic institution.

This is good in unexpected ways. Thanks much.