Small Chinese company empowers Sub-Saharan African women to reclaim reproductive rights

With just over 100 employees, Shanghai Dahua Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd has prevented more than 5 million unintended pregnancies and over 8,000 maternal deaths between 2017 and 2022.

Since the 1990s, the production of subdermal contraceptive implants, a form of long-acting reversible contraception, has been dominated by two pharmaceutical giants—MSD and Bayer—plus a small player, Shanghai Dahua Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, a Chinese firm with just over 100 employees. Established in 1996, Dahua developed its own Sino-implant (II), also known as Levoplant, composed of two silicone rods containing a total of 150 mg of levonorgestrel.

A pivotal moment for Dahua came in 2007 when experts from FHI360, one of the largest and most influential nonprofit human development organizations secured $17 million in funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to enhance the company's technology. By 2018, Levoplant had achieved World Health Organization (WHO) prequalification, a significant milestone that bolstered its credibility on the global stage. Between 2017 and 2022, Shanghai Dahua shipped over 6 million implants to countries and regions outside of China, primarily through international aid organizations like the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). These implants have been instrumental in preventing more than 5 million unintended pregnancies and averting over 8,000 maternal deaths while saving the global healthcare system an estimated $250 million.

Today, women in 31 countries and regions have access to these subdermal implants, a testament to the product's evolving impact on global public health. The formidable challenges Shanghai Dahua faced during the prequalification process were recounted by Zhou Chengjie, Deputy General Manager of Shanghai Dahua Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, in a speech on July 7 at an event hosted by YiXi, a leading brand for speech and presentation events in the Chinese-speaking region, and the Center for Global Development and Health Communication Research at Tsinghua University. The video of Zhou's speech is available on YiXi's official website and the Chinese transcript can be accessed on YiXi's official WeChat blog.

小厂,向前一步

When a Small Chinese Company Took a Step Forward

Hello everyone, I am Zhou Chengjie from Shanghai Dahua Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, a company that has only produced a single product for the past 33 years: a long-acting reversible contraceptive implant.

Before sharing our story, let me tell you the story of a woman named Mariam. She is a Ugandan woman who got married at 12 and gave birth to twins at 13. Two years later, she had triplets, and by the age of 15, she was already the mother of five. Mariam told her husband to do some family planning together, but her husband refused.

By 2016, Mariam had given birth to 44 children, six of whom tragically passed away, leaving her with only 38 surviving children.

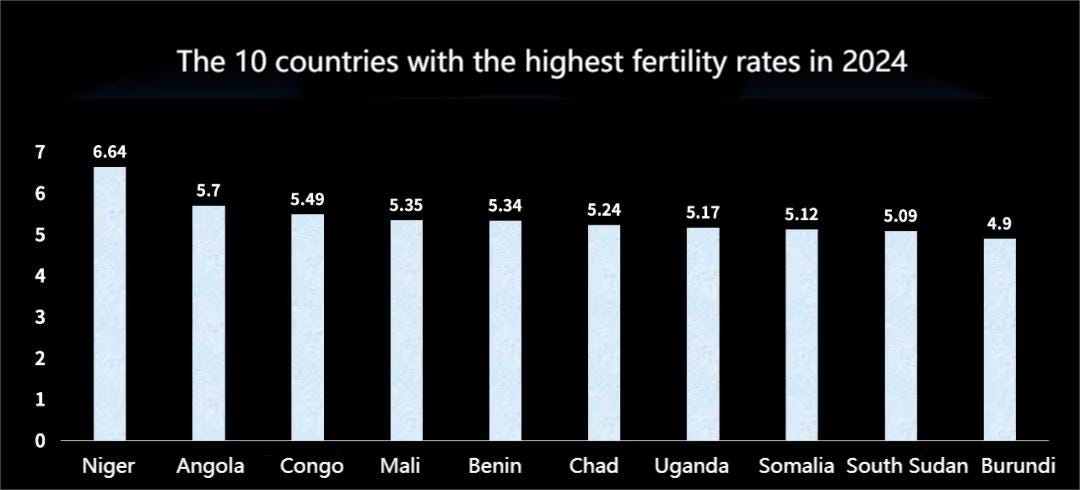

Mariam's story has been widely covered by the media. In Africa, the burden of childbirth on women is enormous. According to United Nations data, by 2024, the top ten countries with the highest fertility rates are all in Africa. In Niger, which ranks first, each woman gives birth to an average of 6.64 children. Even in Burundi, which has the lowest rate among these ten countries, the average is still 4.9 children per woman.

In most parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, the contraceptive prevalence rate among women is the lowest in the world. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), only 26% of women of childbearing age in the region use modern contraceptive methods, meaning methods excluding the rhythm method and coitus interruptus. Additionally, in many underdeveloped areas of Africa, there is often only one clinic within a radius of several hundred kilometers. For example, in a small town called Pibor in Sudan, locals had not seen a doctor in over 20 years until the arrival of Doctors Without Borders (DWB).

Women in Sub-Saharan Africa face two challenges when seeking oral contraceptives or injections: the unavailability of these products and the difficulty of affording long-term expenses. Additionally, their husbands are often unwilling to use condoms.

Therefore, for these women, the longer the contraceptive's effectiveness, the lower the cost, the better—and it's even more ideal if it is reversible. Given the medical conditions and the impact of conflicts, the infant mortality rate in Africa is significantly higher than in China, making the availability of reversible contraceptive methods especially crucial.

Currently, the two main long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are subdermal contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs), the latter commonly referred to as "the ring" in China. However, promoting IUDs in Africa has faced challenges, as many tribes consider the uterus sacred and believe that foreign objects, like IUDs, should not be placed inside it.

As a result, subdermal contraceptive implants are the better option. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized subdermal implants as a safe, effective, and reversible long-acting contraceptive method.

01

In 2006, a nonprofit organization called Family Health International (FHI 360) learned about Dahua subdermal implants. Founded in 1971, FHI 360 is dedicated to researching safe and effective family planning methods. At that time, FHI 360 identified subdermal implants as the most suitable contraceptive products for women in underdeveloped regions such as Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America.

When FHI 360 scholar Markus Steiner learned about Dahua, he was extremely thrilled. Although subdermal implants were convenient, they were very expensive and difficult to promote in impoverished regions. Back then, only three companies worldwide could produce this product—two multinational giants and our small company. Since we primarily sold our products domestically and lacked the qualifications to enter foreign markets, the international market was entirely monopolized by the two multinational giants.

The subdermal implants produced by the two multinationals were priced at $18–21 per set. In contrast, the Dahua product had a significant price advantage, costing only 35 yuan [$4.91] when introduced in the 1990s, and by the early 2000s, even with the addition of the implant syringe, it was still just 38 yuan [$5.33]. Markus was excited about discovering an affordable alternative to the multinational companies' products.

This is the Dahua subdermal implant, a subdermal levonorgestrel-releasing silastic implant, known as Levoplant. It was successfully developed in 1992 through the collaboration of the Shanghai Family Planning Research Institute, the Shanghai Rubber Products Research Institute, and other institutes. The main ingredient, levonorgestrel, is a synthetic and potent progestin, which is also the fundamental ingredient of commonly used emergency contraceptive pills today.

Levoplant consists of two rods, each about 2.4 centimeters long. These rods are implanted under the skin on the inner side of a woman's upper arm by a healthcare professional using an implant syringe. Implantation takes about 2-5 minutes, and the rods can continue to release progestin for several years, providing effective contraception for 3-4 years with an efficacy rate of over 99%.

Because the rods are implanted subdermally, they will not affect daily activities. If a woman wants to conceive, her fertility can be quickly restored after the rods are removed.

Dahua has been producing Levoplant since the 1990s. For many years, nearly all of the company's orders came from the National Health and Family Planning Commission's medicine management center, with annual sales stabilizing at around 100,000 to 200,000 sets. Dahua can survive but not thrive. The employees were content; the work was not busy, and there was no need to work overtime to pursue additional markets.

However, as times change, Dahua's situation is inevitably evolving. The progestin used in the subdermal implants can disrupt the body's natural hormonal balance, leading to some initial side effects. The most noticeable side effects are irregular menstruation and vaginal spotting, which made many women in China reluctant to use Levoplant.

In addition, China's birth policy shifted with the gradual introduction of the two-child and three-child policies. These changes, along with the side effects of the implants, led to a steady decline in sales of Dahua's subdermal implants, dropping from over 100,000 sets per year to just tens of thousands. This decrease put the company in a difficult position, forcing it to confront the prospect of layoffs and salary cuts.

A multinational company with a keen sense of opportunity approached us, planning to acquire the company for 5 million yuan [$701,016]. After the acquisition, Dahua would have been reduced to serving as their original equipment manufacturer (OEM), losing the ability to produce under Dahua's brand.

During the acquisition talks, Dahua's former director, Zhang Guoqiang, flew to Beijing to seek guidance from officials at the National Population and Family Planning Commission. He asked, "A company is looking to acquire Dahua. We are struggling to pay salaries, and the situation is tough. Should we consider selling the factory?"

The leading official at the National Population and Family Planning Commission patted Director Zhang on the shoulder and said, "Zhang, I understand Dahua's difficulties, and China is now in a market economy where businesses must find ways to survive. However, developing China's own products hasn't been easy, and the country has invested a lot in it. You should return and carefully consider your decision."

Director Zhang returned and reflected deeply, recognizing the heavy responsibility on his shoulders. Selling the company would have allowed the two multinational companies to completely monopolize this product, and China would have lost a unique dosage form. After much deliberation, Director Zhang declined the acquisition offer.

02

In 2007, a turning point came. One year after FHI 360 discovered Dahua, they submitted a project proposal to the Gates Foundation. The foundation quickly approved the proposal and provided $17 million in funding support.

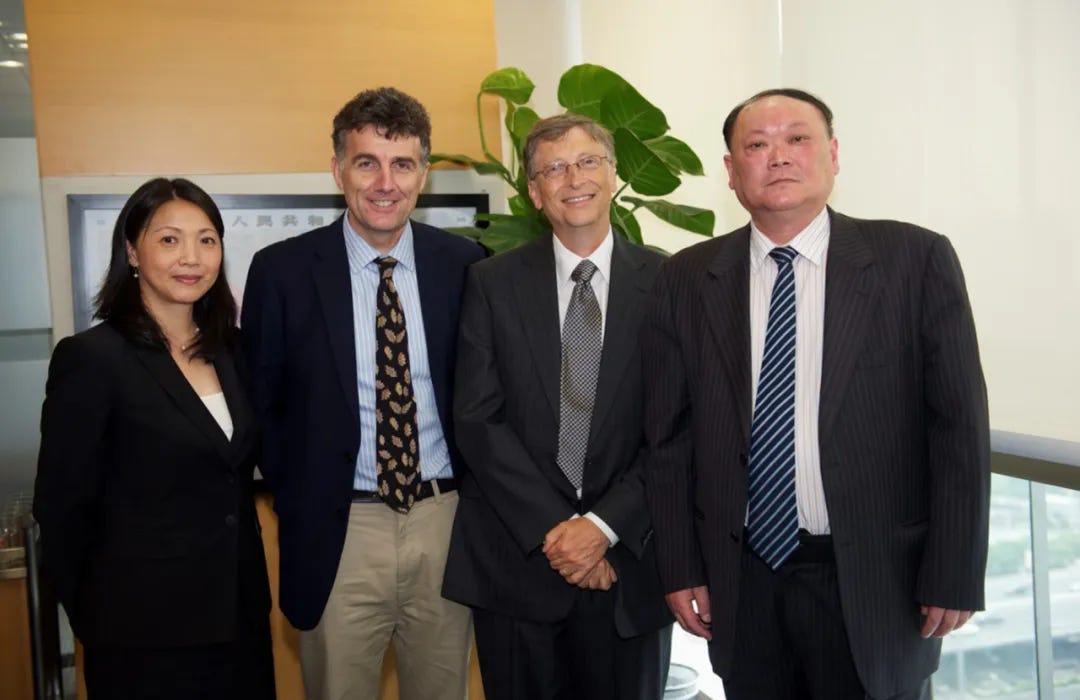

In this picture, the two individuals on the left are experts from FHI 360, with the taller gentleman being Markus. The chubby man on the right is Dahua's former director, Zhang Guoqiang. And the other person everyone knows is Mr. Bill Gates.

At the time, when Markus brought the contract to Director Zhang, we were skeptical: how could there be such a good deal? Someone was offering $17 million to help Dahua upgrade the factory—what was the purpose? Could this be an international scam? The multinational company had only offered 5 million yuan to acquire us, and $17 million could have bought 10 factories like Dahua.

The first time Markus came, the deal didn't go through, but he didn't give up. Markus visited Dahua several times afterward. After continuous communication, we finally understood his intentions.

Markus wanted to bring Dahua's product to the global market so that more women in impoverished regions could afford it. As more people used the product, the market would naturally expand, leading to lower prices and creating a relatively positive cycle. Additionally, introducing a competing product could break the monopoly that multinational companies had on subdermal implants, potentially driving down prices for subdermal implants worldwide.

So, in 2007, Dahua signed an agreement with FHI 360.

The agreement was that, with support from the Gates Foundation, FHI 360 would provide Dahua with $17 million in technical assistance. This would help Dahua upgrade production lines, enhance the quality management system, and conduct clinical trials for product licenses in foreign countries.

In return, Dahua committed to offering safe, effective, and affordable subdermal implants to the global market, particularly in the least developed regions of Africa. Director Zhang also made a verbal promise that, once the company was out of trouble and fully operational, Dahua would donate a portion of its profits to support women worldwide. While the Gates Foundation focuses on large-scale philanthropy, Dahua would contribute on a smaller scale and bring the product to the world.

03

To enter the global market, the first crucial step was obtaining WHO medicines prequalification (PQ). The WHO-PQ is a drug qualification review system established in 2001 to address problems with the quality of medicines and their supply. Obtaining prequalification would allow Dahua's products to participate in international public procurement projects. Major buyers, such as the UNFPA and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), would distribute these drugs free of charge to underdeveloped countries and regions, primarily in Africa.

Dahua was facing a precarious situation, with domestic sales plummeting. Securing prequalification, accessing a stable and large market, and ultimately saving the company became Dahua's sole focus.

In 2010, WHO officially accepted Dahua's application. This picture below was the first time Dahua hosted WHO experts.

Despite having initiated the prequalification application, Dahua was still quite underdeveloped at the time. The company was located on Chongming Island, which is technically part of Shanghai but feels quite different from the city itself. As a native of Shanghai, I had never visited the island before. Prior to the construction of the undersea tunnel and cross-sea bridge in 2009, the only access to Chongming Island was by a half-hour ferry ride, and the journey back home from the island could take up to five hours.

The picture below shows the houses around Dahua, most of which were built in the 1950s and 1960s, older than I am, and are still inhabited today. Although Chongming Island is just a river away from Pudong New Area, Shanghai's most economically developed area, the disparity in economic development between the two regions is stark.

Dahua's factory site, constructed in the 1990s, was relatively modern in comparison to the surrounding area.

Given the conditions on Chongming Island, few college graduates were willing to work there. At that time, the company had about 60 employees, more than half of whom were women working on the production line, and there were only "one and a half" college graduates. It was a joke because Dahua only had one with a bachelor's degree and another who hadn't completed junior college.

It was at this juncture that I joined Dahua. In 2011, Bright Food Group decided to transfer the biopharmaceutical company where I was working, with the hope that our entire team would move to Dahua and work on the evaluation for prequalification.

Initially, I was reluctant to go to Dahua. The company only offered to re-sign my labor contract, but I had other concerns. Having studied biology, often considered one of the most challenging fields for securing a job, I was finally employed, yet the company I worked for was soon to be dissolved. Additionally, the prospect of working on chemical drugs seemed completely unrelated to my field of study. I questioned whether I could effectively apply my skills and whether the new company would offer better career development opportunities.

Before coming to Dahua, I knew little about prequalification. Later, I researched online and discovered that out of thousands of pharmaceutical companies in China, only seven finished pharmaceutical products (FPPs) had acquired WHO-PQ, all from relatively large companies. This finding convinced me that obtaining prequalification would be a worthwhile challenge in my career, so I decided to stay—and remained with Dahua for 13 years.

04

Obtaining WHO-PQ requires the submission of product quality assessments and clinical trial data. The prequalification evaluation process primarily involves assessing product dossiers, conducting on-site inspections of manufacturing and clinical sites, and performing quality control testing of products.

A core principle of prequalification is that the process is more important than the result. If the process is robust, reliable results will follow, but good results alone don't necessarily indicate a sound process. It's like driving—avoiding penalties doesn't mean you're not violating regulations. Many process-related issues can occur by chance; just because they didn't cause problems today doesn't mean they won't cause problems.

When foreign audit experts came to inspect our factory, the first thing they requested was the deviation records from the past five years. Dahua replied that there were no deviations. The two experts looked at each other and burst out laughing, saying, "You must be incredible! This factory has been running for decades, and you have no power failure, tripped circuit, torn piece of clothing, or any other issues?"

We insisted that everything was fine and that there were no issues, but the auditors could immediately tell that was a lie.

The mindset in China was that production should be flawless—any mistakes would indicate a problem with the product. However, the correct approach is to recognize that mistakes are inevitable and not necessarily detrimental. Identifying mistakes allows for correction, and spotting risks enables assessment and mitigation, ultimately improving product quality.

Let me share a small example. Dahua's workshop had 10 rooms, each requiring constant monitoring of the production environment. So the company made it a rule that temperature and humidity in each room had to be recorded every hour. The diligent female workers on the production line followed this rule meticulously. One of them would go from room to room, recording the data. However, every entry on the records was marked exactly at 10:00. Given the time it takes to observe, record, and move between 10 rooms, how could there be no time difference in this process?

This approach violated a fundamental principle: you must record what you observe, and everything should reflect reality. If you enter a room at 10:01, you must record 10:01. Accurate and truthful records are essential so that if something goes wrong, reliable data is available to trace back the issue.

Another key aspect of prequalification evaluation is the quality control testing of products. It's well understood that absolute purity doesn't exist, and raw materials are no exception. Even if impurity percentage is as low as 0.0005%, the question arises: could such a small amount of impurities cause problems?

Dahua assumed it wouldn't be an issue. The reasoning was that the product undergoes terminal sterilization, and as long as it passes post-sterilization checks, there shouldn't be any problems. However, the experts disagreed. They emphasized that even minimal impurity must be identified, and a risk assessment should be conducted to determine whether the impurity could affect product quality.

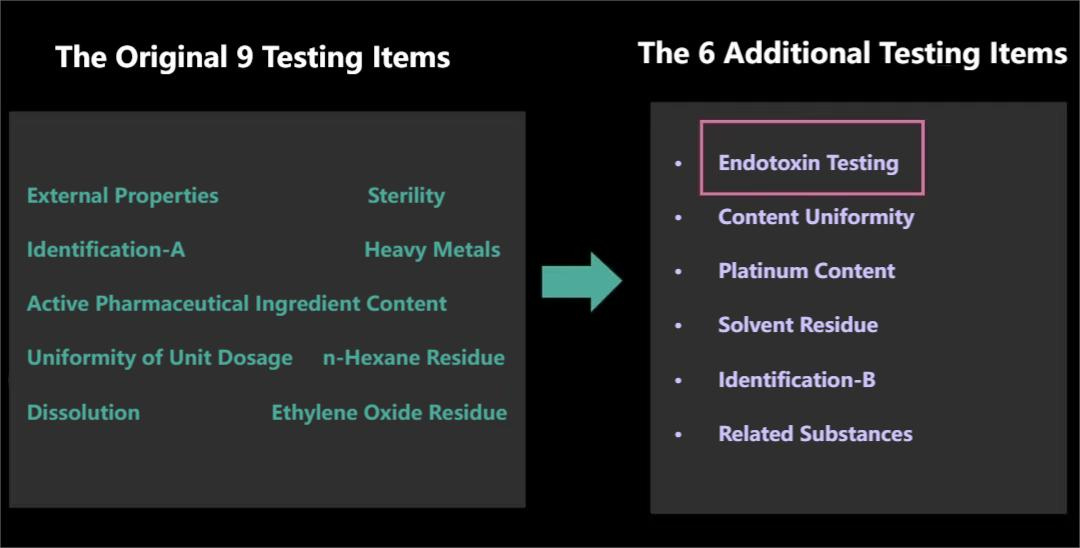

Since Dahua had primarily focused on domestic sales, the testing procedures were based on Chinese national standards, which originally included only 9 tests. However, WHO determined that these 9 tests were insufficient to fully evaluate the product's quality. Consequently, we invested significant human and material resources to add 6 more testing items.

For example, the endotoxin test was added to complement the sterility test previously mentioned. Endotoxins are byproducts of bacterial and microbial metabolism. Initially, Dahua believed that achieving sterility would eliminate any issues. However, while sterility testing ensures that bacteria are eradicated, it doesn't detect the metabolic byproducts they leave behind. If endotoxins aren't tested for, these residual byproducts could remain in the product. Once implanted in the human body, this could potentially cause adverse reactions such as redness, swelling, or infection at the implantation site.

The most challenging of the six additional tests was the final one: measuring the levels of ethylene oxide (EO) and its degradation products.

Ethylene oxide is the gas used for sterilization—it is toxic and highly penetrative. Ethylene oxide can penetrate plastic packaging to sterilize the contents inside without damaging the packaging itself. After sterilization, the package is left to stand for 1 to 2 weeks to allow the ethylene oxide to volatilize naturally. However, any residual ethylene oxide may pose a risk to the human body.

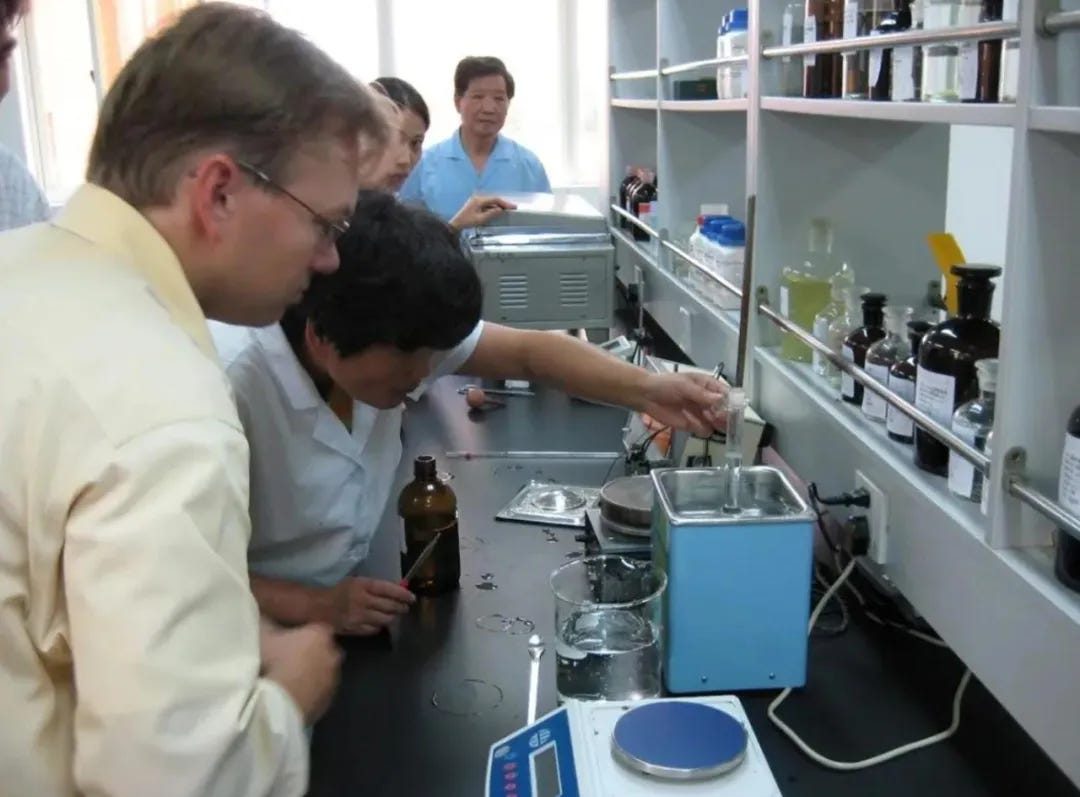

Therefore, Dahua had to determine the acceptable level of volatilization before the product could be released. This photo shows our team conducting relevant research, and the woman in the picture is the sole bachelor's degree holder among the "one and a half" graduates I mentioned earlier. Ultimately, Dahua developed its unique testing method which was recognized by WHO.

After undergoing three on-site inspections by WHO experts over two years, in January 2013, WHO announced that Dahua's subdermal implant had passed Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) certification. This achievement indicated that both the on-site inspections and product control testing met the required standards.

However, to fully obtain prequalification, Dahua's product also had to pass clinical testing.

Dahua initially developed its products in 1992, with clinical research standards and protocols based on the norms of that time. By the 2000s, many of these materials no longer met WHO's updated requirements for clinical research. Consequently, with support from FHI 360, Dahua restarted a four-year clinical research study in the Dominican Republic.

In 2016, Dahua submitted the clinical report to WHO and quickly received approval. Finally, in June 2017, Dahua was awarded prequalification from the WHO.

05

During the six-year prequalification process, the team at Dahua struggled hard. While the 996 working hour system (a work schedule now ruled illegal in China where employees work from 9:00 am to 9:00 pm, 6 days per week) is now widely discussed, back then, Dahua's workers were enduring even longer hours—six days a week, from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m. Despite this grueling workload, not a single team member left.

The female workers on the production line were incredibly kind. We told them, "The company is going through a tough time right now. If you find a better job opportunity, feel free to take it. But if you believe the company still has potential and you're willing to stay, Dahua can pay you the minimum wage. You don't have to come to work; you can take on part-time jobs elsewhere. When Dahua obtains the prequalification and needs to ramp up production, you can return." In the end, over 90% of the women chose to stay with the company.

Thanks to these women who chose to stay, Dahua was able to rapidly restore production capacity when the first orders arrived in October 2017, without the need for extensive training to transition to new employees.

In the same year Dahua passed GMP certification, multinational companies became aware of Dahua's progress toward prequalification. In response, they proactively lowered the price of their subdermal implants from $18–21 to $8.5. After achieving prequalification, Dahua set its product price at $7.5.

Because Director Zhang Guoqiang had pledged that once the company was back on track, Dahua would donate a portion of its profits to support women worldwide, the company further reduced its price to $6.7 in 2021.

This collective price reduction by the three subdermal implant producers enabled Markus to achieve his goal: more women in impoverished regions could now access this essential product. From an international aid perspective, the same amount of charitable funding could now procure more subdermal implants, benefiting several times as many women as before.

In this way, Dahua finally broke the deadlock of "need but cannot afford" regarding subdermal implants.

From 2017 to 2022, Dahua delivered over 6 million subdermal contraceptive implants to countries and regions outside of China, with the majority distributed through aid organizations like the UNFPA. These products have prevented more than 5 million unintended pregnancies and over 8,000 maternal deaths, helping the international community save $250 million in public healthcare costs. There are now 31 countries and regions where women can have access to subdermal implants.

Remember Mariam, the woman with 44 children? Despite having only a second-grade education, she still dreams of providing her children with the education she never had, hoping they can avoid following in her footsteps. No matter how challenging it is, Mariam finds ways to earn money to send her children to school.

"They all have big dreams," Mariam said. "Some want to become doctors, teachers, or lawyers. I hope my children can achieve the dreams that I was unable to realize."

Dahua's mission is to empower women with the right to make their own family planning decisions, helping more women in Africa, like Mariam, to choose whether and when to have children, rather than leaving these decisions to men. This gives them the freedom to shape the lifestyle and future they desire.

I want to express how incredibly honored I feel that Dahua's product has been able to help so many people and contribute, even in a small way, to global health equity. Initially, our goal was simply to keep our factory running and prevent 100 workers from losing their jobs. But now, I can confidently say that Dahua will continue to support the health and well-being of women worldwide.

Thank you.

Gordon G. Liu on China's healthcare reforms, drug innovation & future pandemic response

Gordon Guoen Liu, PKU BOYA Distinguished Professor of Economics at the National School of Development (NSD) and Dean of the Institute for Global Health and Development at Peking University, is a leading figure in health economics in China. In one of a

Ting Lu advises against common "cash handouts" proposal for China's economic slump

Despite Beijing's hesitation, leading Chinese economists continue to advocate for direct cash handouts or consumption vouchers to revive slumping consumption and address high savings rates. At the forefront of this push is David Daokui Li, a professor at Tsinghua University, who

Former Vice Minister of Finance confident in 4.5%-5% growth for 2025-2030

Zhu Guangyao served as China's Vice Minister of Finance from May 2010 to June 2018. After joining the Ministry of Finance in 1985, he has served in various senior positions within the Ministry, including Director-General of the Department of International Economic and Financial Cooperation. From 2001 to 2004, he was the Executive Director for China at t…