Part II of Wei Jiayu: challenges and solutions for educating migrant children in China

Wei Jiayu and Wang Yong highlight the hurdles posed by the hukou system and propose policy changes to improve educational access for migrant children.

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia in Beijing. Today's edition of The East is Read continues from the first part of Wei Jiayu's presentation, where he delved into the statistical intricacies of China's migrant and left-behind children. In this segment, Wei offers his policy recommendations and engages in a discussion with Wang Yong, Director of Hongfan Legal and Economics Studies and Professor of Law at the China University of Political Science and Law, who moderated the seminar. The seminar was organized and its transcript was provided by Hongfan Legal and Economics Studies.

Wei and Hong highlight the educational challenges faced by children of migrant parents in China, mainly due to the household registration system (hukou). This system restricts access to education based on a family's registered location, forcing many migrant children to return to their hometowns for senior high or even junior school entrance exams, disrupting their education and putting them at a disadvantage compared to local students. The disparity in quality between urban and rural schools further results in lower advancement rates for migrant children.

They also discuss "Gaokao migrants" and "returnee students," who move to different provinces to take entrance exams in regions with easier admission to prestigious universities and schools, highlighting the segmented and layered complexities of China's education system.

Additionally, the impact of China's urbanization policy on migrant children was highlighted. The 2014 urbanization plan and household registration reform aimed to control the population of mega-cities by encouraging migration to small and medium-sized cities, yet led to unintended consequences for migrant children. Wei argues that this decision, more than the hukou system itself, influenced migration patterns and education for migrant children until 2019, when the central government shifted its focus to having core cities drive the development of surrounding areas, moving away from the small and medium-sized city strategy.

To address these challenges, Wei suggests revising the Compulsory Education Law to allow children to enroll in schools near their current residence, regardless of hukou. Promoting 12-year education and increasing senior high school construction in areas with large migrant populations would offer more educational opportunities. Easing residency restrictions would facilitate school transfers and Gaokao eligibility for migrant children. A dynamic education model that adapts to a mobile population would ensure educational continuity.

Inclusive public services are essential to integrate migrant families, allowing children to study with their parents. Local solutions show that early planning and community integration can effectively manage migrant education. Support systems promoting vocational education and community engagement through NGOs and public welfare organizations can provide additional resources and support for migrant children.

Wei Jiayu is a Physics graduate student turned NGO leader and currently serves as the Secretary-General of the Beijing Sanzhi Center for Unprivileged Children, formerly known as the New Citizen Program. Sanzhi is committed to raising awareness of issues in children's education through research, communication, and public advocacy. One of their major initiatives is the Wei Lan Program, where Sanzhi staff collaborate with teaching staff, community centers, and volunteers in low-fee private schools. These schools are often the only option for many unregistered migrant children in China, but they suffer from a lack of resources and facilities and face constant risk of being shut down due to their unlicensed status.

Policy recommendations

As Professor Lu mentioned earlier, the issue of compulsory education requires attention. The current Compulsory Education Law of China, with the latest revision in 2006, did not anticipate the large-scale population migration seen today. At that time, the focus was on addressing the educational needs of migrant workers' children. Now, China experiences even more extensive and large-scale migration, but public services remain anchored to the household registration location (hukou). This represents a significant trend.

In many cities, the migrant population accounts for 30%-50%, and in places like Shenzhen and Dongguan, it can be as high as 60%-70%. The focus should be on ensuring that children receive compulsory education and attend schools near their place of residence. Although the Ministry of Education has introduced new measures this year, the efforts are still insufficient. It is crucial to address the root of the issue and revise Article 12 of the Compulsory Education Law which currently states:

School-age children and adolescents shall go to school without taking any examination. The local people's governments at all levels shall ensure that school-age children and adolescents are enrolled in the schools near the permanent residences [hukou] of the school-age children and adolescents.

into

School-age children and adolescents shall go to school without taking any examination. The local people's governments at all levels shall ensure that school-age children and adolescents are enrolled in the schools near the dwelling places of the school-age children and adolescents.

Let's examine another trend: the decreasing birth rates. Despite high pressure for school admissions in recent years, this pressure is expected to diminish rapidly between 2015 and 2025. It is essential to adjust to this trend in advance, rather than waiting until urban schools struggle to enroll enough students. Our approach must be proactive rather than reactive. These trends are clear, as evidenced by the declining birth rates, particularly in the compulsory education stage.

The senior high school and college entrance exams (Gaokao) in China are part of a continuous process designed to provide a "pathway" to future opportunities, but what exactly is this "pathway" like?

The senior high school entrance exam serves as a crucial transition for migrant children from junior high to senior high school. Over the past decade, the proportion of migrant children advancing to high school has increased, both for those migrating across provinces and within a province.

Despite prevalent anxieties, the national average ratio of junior high school graduates advancing to general high schools has remained stable, at around 57%. However, the proportion of migrant children entering high school is about 17 percentage points lower than the national average. This significant gap indicates that the senior high school entrance exam is particularly challenging for migrant children.

My colleagues and I conducted a cross-sectional analysis revealing significant challenges for migrant children in the educational system. Among the migrant children who enrolled for junior high school in 2023, about 10% were migrant children. This percentage drops to approximately 6% at senior high school admission, and by the time they register for the college entrance examination, it falls to only 3%. This shows that at each educational level, the number of migrant children essentially halves, highlighting their diminishing chances of advancing to the next stage. In other words, equal opportunities for migrant children are effectively halved at each step.

Some of these children may return to their hometowns, where they face the challenge of adapting to a new and potentially unfamiliar environment. Their journey toward the college entrance examination is arduous, compounded by the need to plan years in advance. For instance, to take the college entrance examination, a three-year school registration record in the same location as the examination is often required. Consequently, students might need to return home for the senior high school entrance exam, necessitating a move right after primary school graduation. Thus, the impact of these challenges spans the entire educational chain.

This brings us back to Professor Lu's point. Many children are already enrolled in compulsory education in urban areas. When it comes to junior high and high school, shouldn't policies be relaxed to allocate enough spots for them to enroll? However, this alone is insufficient because the later barriers are actually related to the college entrance examination (Gaokao).

Currently, there is a crackdown on "Gaokao migrants" in college admissions. [The Gaokao system, with admission quotas based on provinces, allows students from disadvantaged areas to enter colleges with lower academic thresholds. As a result, some parents send their children to study in advanced provinces but have them take the Gaokao in disadvantaged provinces, where admission to better universities is easier. These students are called "Gaokao migrants."] Unlike the past, most places now advocate for relaxed residency restrictions. Aside from a few cities like Beijing and Shanghai, where policies are particularly strict, most cities have relatively relaxed household registration policies. This has normalized population migration. However, the education system requires several years of preparation (3-5 years) for the Gaokao, which is incompatible with the constant migration of the population.

Even if a family moves from Beijing to Shanghai for work and transfers their household registration, their children still face difficulties transferring schools and becoming eligible for the Gaokao in the new location. It's challenging for them to join the education system at a particular stage and meet the Gaokao requirements. The provincial quota-based Gaokao system is under pressure, and large-scale population migration further challenges the segmented and layered education system.

Policy recommendations:

Popularize 12-year education. Significantly increase the construction of senior high schools in areas with large migrant populations, ensuring more children of migrants can receive senior high school education where their parents reside.

Ease restrictions on school and household registration for migrant children transferring schools and advancing to higher levels. This adaptation is necessary to accommodate large-scale migration in China and new forms of population movement, transforming the education system from a "static" to a "dynamic" model.

Chinese businesses and population are constantly moving, but the education system remains segmented, with each stage taking several years. For the migrant population, school enrollment and entrance exams for junior and senior high schools are significant concerns. However, numerous intermediate changes occur, making school transfers extremely difficult.

Transferring schools is challenging for primary school students, even harder for junior high students, and nearly impossible for senior high school students. Adults can relocate, but it is very difficult for children to move with them, impacting their left-behind or migrant status.

I'd like to share some recent observations: After visiting many places, I've noted that in a static context, the educational path may seem manageable if preparations for enrollment start early. However, many children still do not live with their parents. Recently, many construction projects near my home have resumed, highlighting the plight of construction workers who work away from home for years. The current environment does not support these workers' children living with them.

In contrast, in India, construction sites often accommodate workers' families on-site. This demonstrates that, even if barriers seem low, they can still pose significant obstacles for different groups.

While ensuring education for migrant children may seem challenging nationwide, some places manage it well, providing exemplary models. Jinjiang, a small county-level city under Quanzhou in east China's Fujian Province, has effectively addressed this issue for over a decade. With a population of over 2 million—half of whom are migrant workers—the city maintains consistently high proportions of migrant children in schools from early education through high school. This success demonstrates that early planning, genuine consideration for families, and psychological preparation can make a significant difference. Some children may register locally, thus changing their status to local residents, which could explain slightly lower proportions at the primary and preschool levels.

Lastly, while discussing education pathways, it is important to align the vision with reality. Many people idealize a linear path: good primary, junior high, and senior high schools, followed by university, leading to good opportunities. However, in the Chinese context, pathways are diverse. In recent years, an increasing number of university graduates are struggling to secure jobs. This highlights the need to recognize the variety of educational pathways available. It's essential to collectively imagine these possibilities rather than focus solely on traditional education as the only route to success.

Discussion

Wang Yong:

Thank you, Mr. Wei! I have a few questions. You mentioned that the Compulsory Education Law, last revised in 2006, stipulates that compulsory education is the responsibility of the government of the registered household location. At that time, the authorities didn't foresee that the household registration system would become a significant obstacle as mobility increased in China. Using household registration to define local government responsibilities might have been a significant historical mistake, don't you think?

Wei Jiayu:

I find it difficult to label it as a mistake. Looking at the overall trend in the education of migrant children (which of course began before 2006), from 2006 to 2013, the migrant population increased rapidly, and the scale of migrant children in cities grew quickly. During this period, educational services for this group were relatively more open and progressive. The core issue isn't whether the household registration system was right or wrong, but whether a more inclusive attitude can be adopted toward providing public services to more people in need. The administrative system was moving in that direction, so things progressed smoothly.

However, from around 2013 to 2014, several changes occurred. In 2014, the household registration system reform was initiated. Concurrently, there were significant disagreements about the direction of urbanization. The new urbanization plan and household registration reform in 2014 emphasized "strictly controlling the population of mega-cities," shifting the focus to small and medium-sized cities. This decision, more than the household registration system itself, determined the direction. Meanwhile, many cities like Shenzhen began competing for talent around 2017 and 2018, leading to pronounced conflicts.

By 2019, the central government explicitly stated that core cities should drive surrounding areas, gradually moving away from the "small and medium-sized city" strategy. The household registration issue isn't the core problem; it's more about our judgment of long-term trends.

Wang Yong:

So, the choice of development strategy was the direct cause.

Wei Jiayu:

Yes. I think that had a more significant impact.

Wang Yong:

If the strategy was to strictly control the development of mega-cities, it would have been impossible to accommodate more migrant populations or provide educational services for their children.

Wei Jiayu:

That's right. If the aim is to shrink, you need to control the population. Controlling the population means controlling basic public services, often starting with children.

Wang Yong:

Why was the strategy to control the development of mega-cities adopted at that time?

Wei Jiayu:

This is quite interesting. From my observations, it stemmed from discussions among various economists and sociologists. I studied physics, and after some struggles, I found my stance on urbanization. However, in my discussions with many people, I found this direction of urbanization difficult to judge. It involves not just rational considerations but also many cultural and emotional factors, like nostalgia. Many intellectuals living in cities advocate for rural development because they feel their hometowns are disappearing. So, it's a complex issue that can't be easily explained.

Wang Yong:

Nowadays, there's a consensus, as Professor Lu mentioned, that the development of mega-cities is a direction agreed upon.

Wei Jiayu:

I don't think so. While the central and major economic directions are moving towards that, many people feel that the overall trend is like this, but it might not be what they personally want.

Wang Yong:

From an urban planning and economic development strategy perspective, there's a real divide. But from a legal perspective, the issue becomes more specific. Firstly, you have to acknowledge the reality of a large migrant population in Chinese cities. It's not unique to China; the separation of parents and children is painful for any family. Recognizing this, given the vast migrant population, the state can't base public service provision solely on household registration but on the resident population. Although this has changed later, for a time, it remained unchanged because it relies on the legal responsibilities of the government, not just goodwill. Therefore, local school capacities and student populations should be included in national planning. This is a crucial issue we can delve into later.

You mentioned earlier a comparison with other countries. Despite being a brief mention, I noticed it. For instance, in India, migrant workers often take their families with them. Why does India's situation differ from China’s, given similar early economic development conditions?

Wei Jiayu:

I visited India in 2019. The living conditions in "urban villages" definitely resemble slums. However, it's easier for Indian families to bring their children along, similar to how Chinese migrant workers could easily bring their children along in the early 1990s. Nowadays, the issue in China is finding a place for their children to attend school in the city because Chinese urban schools are significantly better than rural ones. In contrast, Indian public schools are plentiful but very poor. Anyone with any money would send their children to private schools. Nevertheless, children can be easily brought along and placed in a school. Therefore, there's a low threshold for placing a child in school. Some children are even brought along just to live with their parents; many poor people in India have never attended school.

Wang Yong:

In comparison, China didn't provide such accessible, low-threshold schools at the time.

Wei Jiayu:

China did have many so-called migrant worker schools in the late 1990s and early 2000s, without proper licenses. Later, regulations tightened. This brings us back to China's public service system issue. In cities, including "urban villages," China aimed to continually improve public services, but it overlooked that while improving services for registered residents, it effectively built walls, leaving those without local household registration outside these services. Additionally, the presence of tents adjacent to these walls, offering self-provided services, is often not accepted. Thus, it became a two-end scenario: you either cross the barrier to access good services, or you get none. This creates a vacuum, making it difficult for migrant parents to bring their children along. In India, the situation is more fluid, allowing all kinds of setups.

Wang Yong:

It can meet various levels of needs. Is this related to the marketization of schools in India?

Wei Jiayu:

Not really marketization. It's more about the positioning of public schools. Over the years, China has emphasized high-quality and balanced education but often focuses more on quality. Local government departments naturally prioritize serving the registered local population, including those in designated school districts. Parents in these districts consistently feel that existing public services are insufficient and demand improvements. For instance, in Beijing, top schools like the affiliated schools of Renmin University and Peking University overshadow regular public schools, even though they are of high quality. These are all public schools, distinct from the very expensive international schools in Beijing that cost hundreds of thousands of yuan. Since these are public schools, there is a strong desire to continually enhance them.

However, in striving for continual improvement, it's important to remember that the fundamental role of public schools during compulsory education is to ensure that every child receives basic services. Ideally, everyone should have roughly equal access to education. Yet, the quality disparity between schools within the city and those outside it remains significant, and it is almost impossible to bridge this gap. The better the schools inside the city become, the harder it is to level the playing field.

Wang Yong:

Flattening it out.

Wei Jiayu:

Yes, flattening it out. As mentioned earlier, can education become "sufficient" if all schools are built to high standards? For example, the average cost of compulsory education is 10,000 yuan [1,379 U.S. dollars] nationwide, but it's over 30,000 yuan [4,221 U.S. dollars] in Beijing and Shanghai. Is it possible to provide basic services at 10,000 yuan in Beijing? The cost to educate one child in Beijing could serve three children elsewhere. Comparing these metrics is challenging.

Wang Yong:

That's interesting.

Wei Jiayu:

Building a school of lesser quality in Beijing could attract media criticism for being substandard, and registered residents might question its necessity.

Wang Yong:

This is interesting. There are specific reasons why the government hasn't provided basic, average-quality educational services for the migrant population. Understanding these underlying reasons is crucial. Now, considering the continuous decline in China's population and the slowing rural-to-urban migration, will this affect the issues we've discussed? Could it counterbalance? With urban populations decreasing, existing schools might face under-enrollment, potentially addressing migrant education needs.

Wei Jiayu:

While the overall number of children is declining rapidly, rural children are decreasing even faster. This could create a siphoning effect where urban school vacancies might attract rural children more quickly. Despite a general slowdown in rural-to-urban migration, the decline in rural children might actually accelerate.

The reason for this acceleration is that there was previously a shortage of school spots in cities, preventing many children from attending. However, as vacancies in city schools become available, parents might be more inclined to bring their children into the city more quickly. Consequently, the decline in the number of rural children is expected to accelerate in the coming years.

Currently, this trend is particularly evident at the preschool level. The number of children in rural preschools is decreasing rapidly, while the decline in urban areas is slower. In towns, the decline is slightly faster than in urban areas. Therefore, when discussing the overall rapid decline, it is important to recognize that the trends differ between cities, towns, and villages.

Wang Yong:

So, rural children might increasingly move to cities, creating a filling effect, thus the issue persists. This kind of reduces government pressure, almost like saying, "Our schools are empty, come on in!"

Wei Jiayu:

However, this will create significant challenges for junior high and senior high schools, not just enrollment pressure but also other potential conflicts.

Zhang Guohua:

Including situations like the "returnee students" in Xi'an last year.

Wei Jiayu:

Yes, similar issues. We also see people making early decisions about where to take the college entrance exam, influenced by these migration patterns.

Wang Yong:

Will the policy to have more students attend vocational high schools impact this? For migrant children, could this policy result in more migrant students being directed into vocational tracks?

Wei Jiayu:

It's a mixed competition now, so it's quite nuanced.

Wang Yong:

In the urban context, migrant students are certainly at a disadvantage.

Wei Jiayu:

Yes, relatively disadvantaged. However, expectations differ; urban families may be less willing to send children to vocational schools, while some migrant families might be more open to it.

Wang Yong:

Another question for you, Mr. Wei, what does your organization, Beijing Sanzhi Center for Unprivileged Children, primarily do?

Wei Jiayu:

It is a public welfare organization focusing on the education of migrant children.

Wang Yong:

Do you run schools?

Wei Jiayu:

We did in the early days. Our predecessor was the "New Citizen Program" under the Narada Foundation.

Wang Yong:

Did you stop later?

Wei Jiayu:

Yes, running schools is quite complex. We now collaborate with low-fee private schools on many projects. One project, "Weilan Library," involves volunteers helping these schools set up and operate libraries.

Part I of Wei Jiayu: statistical discrepancies and systemic barriers of China's migrant and left-behind children

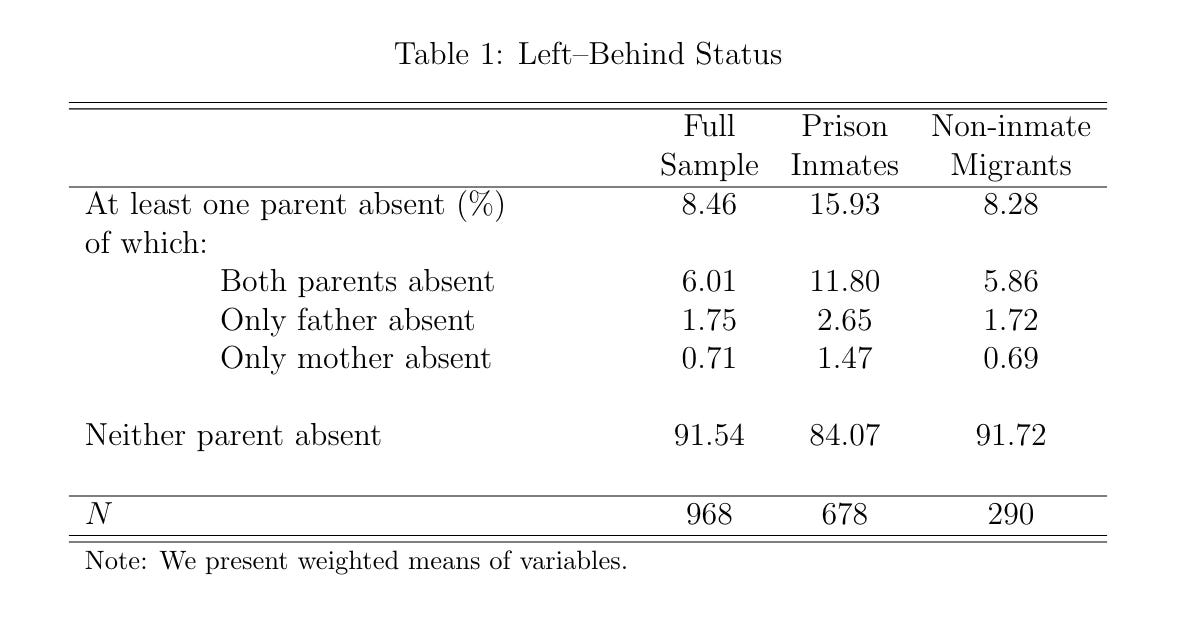

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia in Beijing. Following the publication of Professor Lu Ming's advocacy for "spatial restructuring" in China's urbanization process and Professor Zhang Dandan's study on adulthood criminality among left-behind children, the third installment of the April 27 online seminar organized by

Lu Ming calls for better services for "left-behind" children in China's "spatial restructuring"

Every citizen in China is registered under the hukou 户口 system, a household registration system primarily determined by their place of birth, which dictates their access to social services. Consequently, individuals born in less developed regions are entitled to lower-quality education and healthcare, predominantly provided or managed by local governmen…

Zhang Dandan: "very strong correlation" between left-behind childhood and criminality in adulthood

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia from Beijing. Following Lu Ming's presentation, today's post focuses on a quantitative econometric study examining the causal relationship between being left behind in childhood and committing crimes in adulthood. Same as Professor Lu, this presentation was originally delivered at an April 27 online seminar organized by