Lu Ming calls for better services for "left-behind" children in China's "spatial restructuring"

China must facilitate rather than stall or discourage public services for the children of 400 million migrant workers, says the Shanghai professor and advocate for bigger, more populous cities.

Every citizen in China is registered under the hukou 户口 system, a household registration system primarily determined by their place of birth, which dictates their access to social services. Consequently, individuals born in less developed regions are entitled to lower-quality education and healthcare, predominantly provided or managed by local governments.

Although there are growing opportunities to transfer one's hukou to more prosperous areas, the process remains prohibitively challenging for many, particularly for the hundreds of millions of migrant workers whose hukou remains tied to rural areas despite years of employment in more developed cities. This restriction extends to their children, limiting their access to better services and opportunities.

As the Communist Party of China has vowed that reforms will top the agenda of the 3rd Plenary Session of its 20th Central Committee in July, how the world's second most populous country will approach the much-anticipated hukou reform, perhaps a part of diminishing the legal and institutional urban-rural divide, and its related public services provision, is keenly watched.

Lu Ming, a prominent advocate for expediting the urbanization process, argues that integrating rural residents into urban life and education from childhood is crucial. He believes the growing service sector, the key to China's economy as the population dividend diminishes, requires skills developed through urban experiences, such as communication, stress management, creativity, and initiative.

Lu shows that early migration from rural to urban areas enhances the acquisition of these non-cognitive skills, improving employment prospects in the service sector and increasing income levels. Conversely, delaying migration can lead to missed opportunities for essential urban experiences, negatively impacting future job opportunities and income.

Making a key contribution to China's public opinion, Lu convincingly refutes the dominant line that the central government of China, a unitary state with no federalist system, should discourage population flows out of rural or rust belt regions, such as northeastern China. Skillfully taking advantage of the overarching political goal of 共同富裕 "Common Prosperity for All," Lu credibly shows that enabling free migration across provinces and regions benefits China as a whole, overriding the concerns for the so-called “hollowing out” of some regions.

Although he sat at the Chinese Premier's roundtable on Jul. 6, 2023, it's unknown if Lu's argument along those lines will change decision-makers’ minds, but in our observation, it has yet to penetrate China's mainstream view.

Moreover, Lu's research shows that individuals who move to reasonably sized cities, or "true cities," experience significant benefits, with even greater effects observed in large cities. This highlights a key aspect of China's urbanization process, where county-level and prefectural-level cities often do not meet the standard expectations of a "city" in terms of economic structures and opportunities.

Lu Ming is a Professor at the Antai College of Economics and Management at Shanghai Jiaotong University and Executive Dean of its Shanghai Institute for National Economy.

He is also the author of a popular book on the Chinese economy and demographics — Great Nation Needs Bigger City 大国大城, which evaluates urban and regional development policies and advocates for relaxing hukou and promoting domestic market integration. A sequel to the book, Centripetal City 向心城市, has just been published this year.

The following presentation was originally delivered at an April 27 online seminar organized by Hongfan Legal and Economics Studies and the video remains accessible. Hongfan provided The East is Read with a text transcript of the seminar. The East is Read has previously featured another seminar by the institute in December 2023.

The seminar was hosted by Wang Yong, Director of Hongfan Legal and Economics Studies and Professor of Law at the China University of Political Science and Law, as seen in the picture below.

解决留守儿童问题,推进中国式现代化

Addressing the Issue of Left-Behind Children to Advance Chinese Modernization

Chinese modernization, as outlined by the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) is a crucial development goal. In my view, this modernization process will inevitably involve what I call “spatial restructuring” of China’s economy and society. Despite diminishing demographic dividend and declining labor force since 2015, there is no need for undue concern as China undergoes spatial adjustment. Currently, agriculture accounts for only 7% of China's GDP, while the manufacturing and service sectors continue to grow.

From 2010 to 2022, China's urban population increased by 37%, and employment in the secondary and tertiary industries grew by 15.6%, from 480 million to 560 million. This shift indicates that Chinese modernization should rely on population migration from rural to urban areas and from agriculture to secondary and tertiary industries. Facilitating the free movement of people will enhance labor resource utilization efficiency. Currently, the urban-rural income gap remains 2.4 times, and regional disparities in per capita GDP and disposable income are 4.23 times and 3.42 times, respectively. This constitutes a spatial restructuring dividend.

Furthermore, China should enhance its labor force quality by transitioning from the current 9-year compulsory education to 12-year compulsory education. This broader context sets the stage for addressing the issues of left-behind and migrant children today.

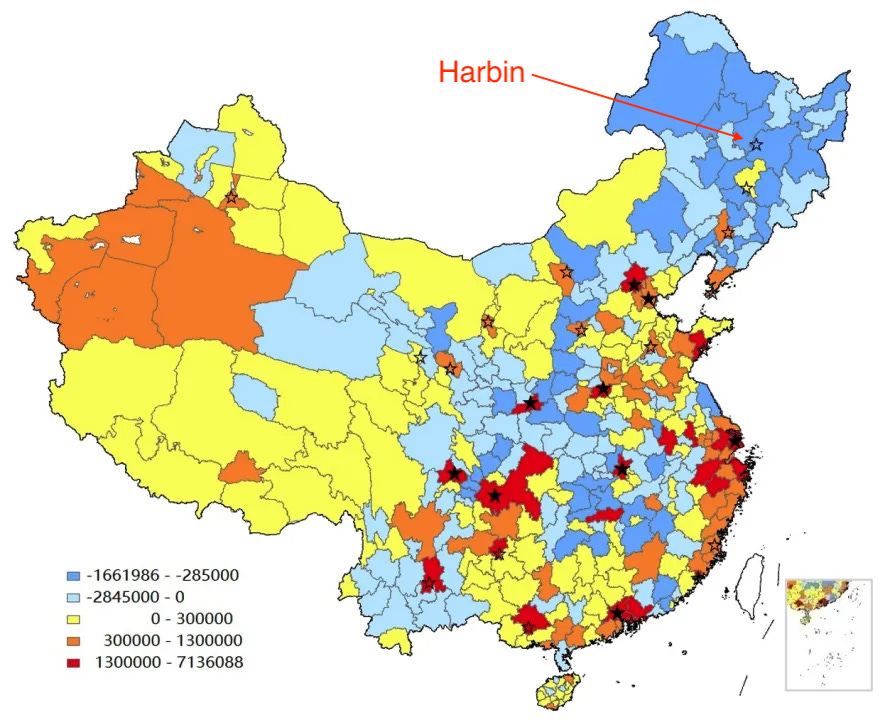

Given the process described, let's examine the current trends in population movement in China.

Approximately 400 million people are currently on the move. In terms of spatial distribution, as shown in this map, the red and yellow areas represent population growth according to the latest census. Apart from the ethnic minority regions in the northwest, the population is increasingly concentrated in coastal areas and major cities on the eastern side of the Heihe–Tengchong Line [an imaginary line that divides China into densely populated east and sparsely populated west regions].

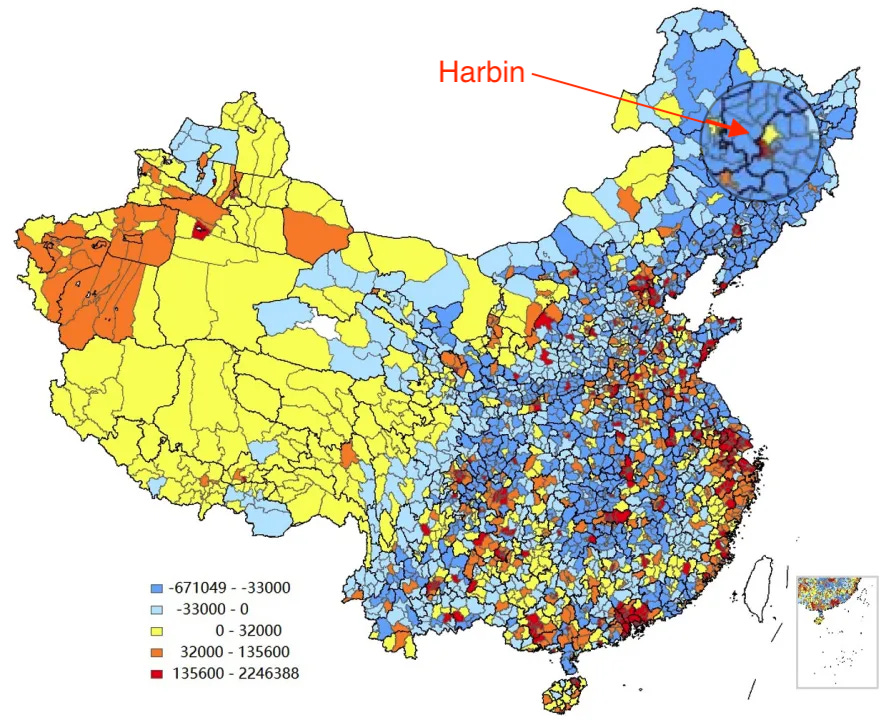

Examining population movement at the district and county levels, there is a clear trend towards central urban areas. For instance, in Harbin, a well-known city in the northeast, the left map shows overall negative population growth. However, the right map indicates positive population growth in its central urban areas, as highlighted by the arrow in the top right corner.

With modernization and the increasing significance of the service sector, services have become the main driver of job creation in China. Employment in the primary and secondary sectors is declining, while the tertiary sector shows positive growth. The service industry's development, which requires face-to-face interaction unlike manufactured goods that can be transported, leads to a migration of people towards more populous areas. This results in the trend of population migration to cities, large cities, and central urban areas.

Given this trend, many people worry about potential imbalances in development between different regions. However, the free movement of labor is actually beneficial for achieving common prosperity for all. Let me briefly compare China, the United States, and Japan.

For each country, I have drawn three lines. The red line indicates the GDP disparity between different cities within the country. The higher the red line, the greater the GDP gap between large and small cities. In the United States and Japan, the GDP disparity between different cities is significant, with the economy highly concentrated in a few cities. But this is not a cause for concern because their populations are also highly concentrated.

The blue line shows that the population disparity between cities in the United States and Japan is also significant, closely matching the GDP disparity. This means that economic concentration is accompanied by population concentration, leading to minimal differences in per capita GDP across different cities in both countries.

Now, looking at China, the GDP disparity between different cities is similar to that of Japan. However, the population disparity between cities is much less pronounced compared to the concentration of economic activity. Consequently, while economic activity is concentrated, the population is not, resulting in a higher per capita GDP disparity. Fortunately, as observed earlier, with the ongoing population shift towards coastal areas and major cities, the per capita GDP disparity between cities in China is narrowing, as indicated by the declining black line.

This provides context for understanding the future of Chinese modernization. It suggests that both economic activity and population will increasingly concentrate in a few regions, leading to balanced development in per capita terms. This will help overcome the current challenge of diminishing demographic dividends. By facilitating population movement, labor productivity and resource allocation efficiency will improve, providing long-term momentum for economic and social development. This is the current background of population movement in China.

Some of you might wonder, especially if you're not from an economics background, why people are moving to large cities. Modern economic research explains this with two mechanisms found in cities:

1. Human capital externalities. When people, especially university graduates, work in the same city, they learn from each other, enhancing each other's productivity. Research I conducted with Professor Glaeser from Harvard University shows that if a city's average education level is one year higher than another's, its per capita income is 21% higher. This is why so many people are drawn to big cities.

2. Skill complementarity. You might understand why graduates move to big cities, but why do many workers with lower education levels also flock there? This relates to the second economic characteristic: skill complementarity. As large populations concentrate in cities, production processes, despite technological advancements, still require many support roles, such as operators, cleaners, and cooks. Additionally, as living standards and population density increase, the demand for various life services also rises, creating jobs in domestic services, food delivery, and other areas that do not require high educational levels.

Globally, people moving to big cities typically fall into two categories: those with higher education (university level or above) and those with lower education levels (primary or secondary school) who take on numerous service industry jobs. Conversely, individuals with intermediate education levels are less likely to move across regions. Given this trend, a significant amount of population migration occurs across regions.

In 2021, Professor Wei Dongxia and I published an article in the Economic Research Journal addressing another aspect of this issue. Although many people, given time, acknowledge that population migration is important, they believe it should not be rushed. Our research suggests otherwise: it should be expedited. Why? Because the skills required by the growing service sector are not taught in schools but are developed through life experiences in cities. These include non-cognitive abilities like communication, stress management, creativity, and initiative.

Professor Wei and my study found that individuals who migrate from rural to urban areas early are in a better position to acquire these non-cognitive skills, increasing their chances of employment in the service sector which relies heavily on interpersonal interactions. As a result, they have a higher probability of achieving higher income levels. If early migration of rural residents to urban areas is not facilitated, they may miss the critical period in childhood and adolescence for accumulating urban living experience, negatively impacting future employment opportunities and income, especially in service-oriented jobs.

This ties into the issue of "left-behind children." Many left-behind children receive their middle school education, and even the latter years of elementary school, in rural areas. As a result, they lack crucial urban living experiences until they enter the job market in adulthood, negatively impacting their employment opportunities and income potential.

Furthermore, the destination of migration matters. Migrating to small towns does not yield the same learning effects as moving to larger cities. Significant learning effects, which boost employment and income, are observed when individuals migrate to and secure stable employment in reasonably sized cities (what I call "true cities"), with even greater effects in large cities. Interruptions, such as returning to rural areas after migrating, weaken these learning effects. Therefore, continuous urban residence is essential for accumulating valuable experience, ultimately benefiting one's performance in the labor market.

Additionally, Profesor Wei and I conducted a data analysis to examine the spatial differences in the returns on education. The horizontal axis of this graph represents population size, and the vertical axis represents the returns on education—specifically, the increase in income resulting from higher education levels. The graph shows that larger cities, particularly the four first-tier cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, offer higher returns on education. This helps explain the continuous migration of people towards these major cities.

Findings show that if a city's population doubles, the returns on education can increase by 0.6 percentage points. The policy implications are significant: current systems, such as the household registration (hukou) system or unequal public services, hinder labor mobility. For instance, during certain periods, super-large cities have implemented policies to control population growth by raising the threshold for migrants to settle. These barriers reduce opportunities for people to move to big cities, limiting their potential for higher income and better returns on education.

Conversely, consider the perspective of a rural resident. If they anticipate that completing their education will not allow them to move to areas with higher income potential, their motivation to pursue education diminishes. As previously mentioned, the returns on human capital education are crucial. With the demographic dividend diminishing, the next focus should be on the quality dividend. This necessitates the universalization of high school education.

The current state of restricted labor mobility is exactly what leads rural residents in China to question the value of the education they receive, thinking, "What's the use of getting an education if I won't be able to earn a higher income anyway?" This creates a conflict between controlling population growth and universalizing education to achieve a quality population dividend.

This brings us to the context of today's discussion on "left-behind children." Despite the large scale of migrant populations, their children often do not have equal educational opportunities in cities. As a result, there is a significant number of migrant and left-behind children. According to the 2020 China Population Census Yearbook, there are over 70 million migrant children under 18 years old. These "migrant children" are defined as those whose parents work in a different place where they do not hold local household registration, and the children live with them. This group makes up 23.88% of all children in China, nearly double the size it was in 2010.

Another metric to consider is "left-behind children," those who do not live with either one or both of their parents. Data from a report jointly published by the National Bureau of Statistics, UNICEF, and UNFPA on the 2020 status of children in China shows that there are over 60 million left-behind children. Not all of these children remain in rural areas; increasingly, some stay in county-level towns, becoming urban left-behind children. Combining the 70 million migrant children and the over 60 million left-behind children, the total reaches nearly 140 million. This means that about one-tenth of China's population and a significant proportion of its children are in a state related to inter-regional migration, either as migrant children or left-behind children. This situation poses a substantial challenge to Chinese modernization.

Some left-behind children face various social issues, which other experts will also address. While many people recognize its importance and the need for solutions, resolving the problem of left-behind children remains contentious after a decade of debate. Recently, there has been some progress, but many still argue that having a large number of children migrate to big cities for education creates significant pressure on the urban areas. Consequently, some suggest that parents should simply return to their hometowns to care for their children. Others question the sense of responsibility of these migrant parents for leaving their children behind.

Addressing the issue of left-behind children requires a long-term, holistic perspective, or what economists call a "general equilibrium perspective." Ignoring the economic laws underlying labor mobility and using either coercive or economic incentives to force young parents to return home fails to consider why they migrated in the first place: to pursue higher incomes. Forcing them to return would significantly reduce their income and create labor shortages in the cities where they currently work. When a super-large city in China restricted migrant populations, for example, local life became inconvenient due to a reduction in domestic and service workers, leading to increased service prices.

In a unified country like China, leaving a large number of young workers in rural or small towns without income growth opportunities means the state must increase fiscal transfers to underdeveloped areas to achieve common prosperity, adding financial pressure.

Reforming the system to allow more left-behind children to migrate with their parents and receive education in the cities where their parents work would have multiple benefits. It would promote family reunification and significantly improve education quality while aligning with the urbanization process. As these children migrate to cities, they can benefit from the learning effects of urban living, better preparing them for the future labor market and advancing Chinese modernization.

Given this explanation, it's encouraging to observe that since last year, and especially this year, there have been many positive signals regarding hukou system reform and the education of migrant children. For instance, the 2024 Government Work Report emphasizes, "The new urbanization strategy was further advanced. Restrictions on hukou approvals were further relaxed or lifted, the overall carrying capacity of county seats was increased, and the share of registered urban residents in the total population rose to 66.2 percent."

Recent statements from the government and the National Development and Reform Commission also highlight, "As a matter of priority, we will move faster to grant hukou to eligible people who have moved to cities from rural areas. We will deepen reform of the household registration system and refine the policies for linking transfer payment increases and the amount of local land designated for urban development to the number of hukou approvals local governments grant." This means that cities attracting more migrant residents will receive more construction land quotas and additional fiscal transfers related to public services, aligning the flow of people, land, and funds to enable willing migrant workers to settle in towns and ensure that non-registered residents can equally enjoy basic urban public services.

In terms of education, the Government Work Report says, "We will ensure that left-behind children in rural areas and children in need receive adequate care and assistance."

In terms of accelerating hukou system reform, the future goal should be to ensure that for migrant populations with long-term stable employment and residence, the urbanization process should be expedited based on the primary standards of actual residence duration and social security payment duration.

Additionally, progress is anticipated toward the cumulative recognition of points for household registration across megacities with similar economic development levels. For instance, if someone has lived in Nanjing for three years and then in Suzhou for five years, their accumulated points should count towards obtaining household registration in Hangzhou in the future.

Moreover, during the urbanization process, some people may not immediately obtain local hukou. The objectives of certain local governments [such as Guangdong] have already stated that "public service resources should be allocated according to the resident population." For large cities, particularly in the context of today's construction of new suburban cities, breakthroughs can be made first to attract residents.

According to data provided by the Ministry of Public Security of China, since 2023, the pace of hukou system reform has indeed accelerated. Except for a few extremely large cities in the eastern regions and in a few provincial or capital cities in the central and western regions, restrictions on household registration have been largely lifted. Relevant authorities are also encouraging the remaining super-large cities to introduce policies that facilitate the registration of ordinary workers. This could significantly impact the hundreds of millions of people discussed earlier.

Shenzhen, in particular, has set an example by improving its points-based household registration system, ensuring that social insurance payment duration and residence duration constitute the primary factors. Additionally, it promotes the online application for residence permits for the migrant population and introduces measures to explore the convenience of the residence permit system. In the future, holding a residence permit will grant access to an expanding range of basic public services, with continuously improving quality.

Recently, the Ministry of Education of China issued a directive titled "Notice on Launching the Special Action for Sunshine Enrollment in Compulsory Education." One of its provisions says, "Local educational authorities should ensure the enrollment of special groups, including dropout children, children of migrant workers, left-behind children, and children with disabilities. The aim is to ensure that all school-age children and adolescents receive compulsory education equally."

These recent policy directions are encouraging. Based on research and discussions with Professor Wei Jiayu, who will also speak today, the following actions are recommended:

Amend the Compulsory Education Law. Currently, Article 12 of the law states, "School-age children and adolescents shall go to school without taking any examination. The local people's governments at all levels shall ensure that school-age children and adolescents are enrolled in the schools near their registered residences." This should be changed to "near their place of residence."

Increase educational fiscal investment. The current benchmark for educational investment in China is 4% of GDP. Increasing this to 4.5%, and in areas with larger populations and more schools, up to 5% or even 6%, would be beneficial. This approach aligns with practices in developed countries. Additionally, central government fiscal transfers related to education should be linked to the number of urban residency approvals and the number of their children enrolled in urban schools.

Local governments in areas with population inflows should increase their educational investments. If funding is insufficient, several measures can be taken, such as issuing bonds related to the urbanization of migrant populations and encouraging private enterprises and social organizations to run schools. Educational authorities should focus on regulating the content and quality of education while providing financial and land support to private education institutions. Given that migrant populations often have lower incomes and busy work schedules, funding and space should also be allocated to support out-of-school education and care for migrant children, extending coverage to low-income urban families and single-parent households.

Refine local government assessments for public school enrollment proportions. Current assessments are stringent, leading some local governments to close many private schools, particularly those serving migrant children, to increase the proportion of public school enrollments. While this seemingly increases the proportion of public education, it does so at the expense of overall educational capacity. This practice should be revised. If assessments are necessary, they should focus on the proportion of migrant children receiving education locally rather than strictly in public schools, especially if public educational resources are insufficient.

Gradually expand to 12 Years of compulsory education. While high school is yet to be compulsory, efforts should be made to increase the coverage to 12 years. As migrant populations become urbanized and public services become more equal, excluding high school education for migrant children will force many to return to their hometowns for high school and college entrance exams, perpetuating the issue of left-behind children.

Enhance care for left-behind children. Solving the issue of left-behind children cannot be achieved overnight, so care for those remaining in their hometowns must be strengthened. Studies have shown that children born in cities who later return to their hometowns for education often struggle to integrate into the local educational system, affecting their educational and psychological well-being. These children, sometimes unfamiliar with the local dialect, may be treated as outsiders and face bullying. These issues require the attention of relevant authorities and society at large.

On the 3rd Plenary Session coming up in July

More from Hongfan Legal and Economics Studies