Part I of Xu Gao: corporate gains fail to boost household income, leading to over-investment & excessive savings in China

Blocked income transfer from enterprises, especially SOEs, to households is identified as the key culprit behind China's unusually high savings rates, leading to low consumption & slow growth.

On March 13, 2024, the National School of Development (NSD), Peking University, in collaboration with Baidu Economic & Financial News, held the 68th session of the China Economic Observation Report event and launched the 30th-anniversary celebration of the NSD.

Several leading Chinese economists participated in the session, offering their assessments of China's economic landscape and their visions for future development, especially against the just-concluded "Two Sessions." The East is Read has already published a speech by Lu Feng from the event. Another speech by Justin Yifu LIN has also been published by Pekingnology, a sister newsletter of The East is Read.

Today's The East is Read will feature Xu Gao, the Chief Economist and Assistant President of Bank of China International Co. Ltd., leading the research department and sales and trading department of the company. He is also an adjunct professor of the NSD at Peking University.

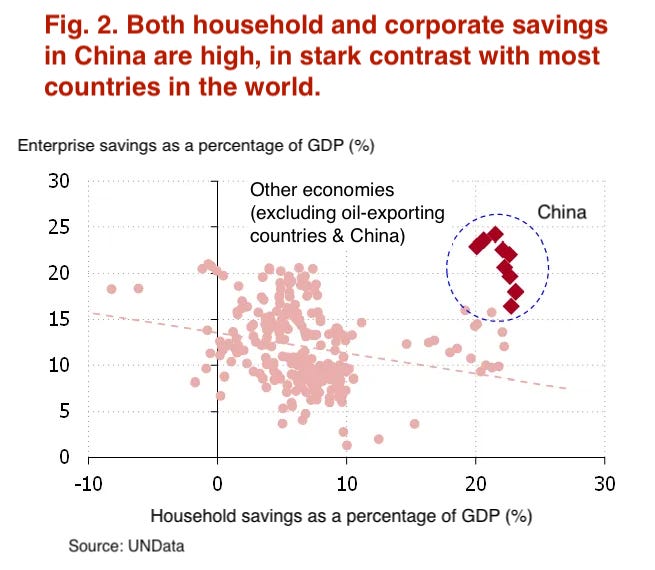

Xu argues that the significantly lower consumption-to-GDP ratio in China, compared to the global average, is the fundamental cause of the country's lackluster domestic demand and economic slowdown. He attributes this low consumption level to unusually high savings rates, with both enterprise and household savings rates remaining notably elevated. This is in stark contrast to other economies where the two rates typically exhibit a negative correlation.

Xu highlights the profoundly obstructed channel of income transfer from the corporate to the household sector as the primary reason behind this distinctive consumption pattern. The extensive presence of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China, whose profits and dividends primarily flow to the state rather than households, diminishes the wealth effect that might otherwise stimulate household consumption. Nor is the highly concentrated ownership of many Chinese private enterprises doing much to increase the wealth or consumption of the wider population.

Furthermore, Xu points to the absence of an efficient market mechanism (again, a result of the disconnect between the corporate and household sectors) to balance the distribution of national income between consumption and investment. This shortfall means the household sector is unable to influence corporate dividend policies, resulting in excessive corporate savings and overinvestment.

The original video recording of the speech is available on the NSD's official WeChat blog. Please note the following translation is derived from Xu's personal transcript of his speech, in which he included additional details and structured the content more systematically. The Chinese version can be found on Xu's personal WeChat blog 徐高经济观察 Xu Gao Economic Observation and was also cross-posted to the NSD's official WeChat blog.

This is the first half of Xu's speech. The latter half is also available on The East is Read.

I am honored to present at the 30th anniversary of the NSD, during its flagship event, the China Economic Observation Report. I would like to take this opportunity to discuss a comprehensive analytical framework for China's mid-to-long-term development. In fact, defining a medium-to-long-term analytical framework simplifies addressing short-term issues.

My overarching framework is straightforward. It is premised on the observation that China's income distribution structure has led to insufficient consumption, leaving the country with three strategic pathways: optimal, suboptimal, and non-optimal. The primary driver behind China's recent economic slowdown is the erroneous selection of the non-optimal strategy.

My discussion will start with the issue of insufficient consumption driven by China's income distribution dynamics.

China’s key problem lies in insufficient consumption

The 2021 Central Economic Work Conference already identified the threefold challenges confronting the Chinese economy: demand contraction, supply turbulence, and weakening expectations. Currently, even though the pandemic has subsided and supply shocks have been addressed, the country continues to grapple with intensified dual pressures from demand contraction and weakening expectations.

Demand contraction is not new; it has persisted since the late 1990s. Weak domestic demand, compounded by lackluster external demand or export volumes, results in insufficient total demand, thereby stifling economic growth. In that sense, the long-term growth constraints on the Chinese economy lie not in the supply but in demand.

Aggregate demand comprises three components: consumption, investment, and trade (imports and exports). Consumption and investment are pillars of domestic demand, whereas trade reflects external demand. The root cause of insufficient domestic demand is insufficient consumption; that is, the consumption-to-GDP ratio is too low.

Transnational data show that, at a per capita GDP level of over $10,000 (calculated in constant 2005 prices), the average proportion of consumer spending to GDP is around 55% across countries worldwide. However, as per capita GDP in China increases, the proportion of consumer spending to GDP continues to decline, now almost 15 percentage points lower than the global average. Even if government consumption is added, the total consumption to GDP ratio in China is still about 15 percentage points lower than the world average. (Fig. 1)

A low consumption-to-GDP ratio signals that the benefits of economic growth have not fully translated into the welfare of the people. The objective of economic growth is to fulfill the people's expectation for a better life, which is primarily manifested through their expectation for enhanced consumption—better quality food, clothing, and leisure activities. When a country's consumption constitutes a small fraction of its GDP, it indicates a misalignment between the aggregate economic growth (as depicted by GDP) and the lived experiences of its people.

Since national saving is defined as a nation's income minus consumption, a low consumption-to-GDP ratio inherently suggests a high savings-to-GDP ratio, reflecting two facets of the same scenario. Currently, China's national savings rate, represented as a percentage of GDP, is over 40%, roughly double the global average.

In the dynamics of consumption and investment which constitute domestic demand, consumption represents the ultimate demand, whereas investment is seen only as a derivative demand. Typically, investments are made with the expectation of earning returns. When these expected returns diminish, so does the incentive to invest. Without a spontaneous flow of income from investors to consumers that induces more consumption, a scenario of weak internal demand emerges, characterized by both tepid consumption and investment levels. Consequently, the persistently low level of consumption-to-GDP ratio in China signals a long-term shortfall in domestic demand.

The disconnect between the corporate and the household sector leads to a high savings rate in China

To understand the reasons behind China's low consumption and high savings rates, one can approach it from either the consumption or savings perspective. In the following analysis, I shall focus on savings as the analytical lens to uncover the factors driving China's distinctive pattern of low consumption and high savings.

The national saving stems from three sources: households (consumers), enterprises, and the government. Among these, government savings are relatively minor, so the bulk of the national saving is derived from households and enterprises.

Household savings are derived by subtracting consumption from households' income, while enterprise savings are similarly calculated as enterprises' income minus their consumption. It's important to highlight that in this context, "enterprise income" refers to the concept as defined within the National Economic Accounting framework, which means the income of enterprises after the distribution of dividends; this is distinct from the revenue figures reported in financial statements. Given that enterprise consumption is accounted as zero, enterprise savings effectively represent the profits retained post-dividend distribution.

China's economic landscape is uniquely characterized when comparing enterprise and household savings internationally. Analysis of data from the past decade across most countries reveals a negative correlation between enterprise savings and household savings: a low ratio of enterprise savings to GDP usually coincides with a high ratio of household savings to GDP, and vice versa. However, in China, both enterprise and household savings ratios to GDP are notably high, lacking the negative correlation observed in other countries. This situation in China is markedly different from that in most other countries. (Fig. 2)

In most countries around the world, the observed negative correlation between corporate and household savings can be attributed to the fact that when households hold company equity, income distribution shifts between the corporate and the household sectors do not alter the overall wealth level of these households. Let me illustrate with a simple example.

Consider an additional income of 100 yuan is generated. In the first scenario, this income is directed to the household sector and saved in a bank, leading to a 100-yuan increase in the household sector's assets (reflected in household bank deposits), thereby augmenting the total wealth of the household sector by the same amount.

In the second scenario, instead of flowing to the household sector, the 100 yuan are allocated to the corporate sector and similarly saved in a bank. Consequently, the corporate sector's assets grow by 100 yuan (reflected in corporate bank deposits). However, this is not the end of the story. As the corporate sector's assets swell, the valuation of the company's stock rises by 100 yuan as well. If these company shares are owned by the household sector, the total assets—and thus the wealth—of the household sector also see an increment of 100 yuan.

Hence, if the corporate sector's equity is predominantly owned by households, the route of income—whether through the household or the corporate sector—ultimately consolidates as household wealth. This means that as long as households hold corporate equity, both corporate and household savings contribute to household wealth. This income distribution mechanism between the corporate and household sectors does not impact the aggregate wealth of households. In Economics, this rationale is encapsulated in the concept known as "piercing the corporate veil." (Fig. 3)

However, the above conclusion holds on the precondition that the equity of the corporate sector is held by the household sector, which significantly deviates from the extensive presence of SOEs in China. Of course, SOEs in China are technically owned by the people, yet their equity is predominantly held by the state. Consequently, the dividends from SOEs primarily flow to the state rather than the households; the profits retained post-dividend distribution from SOEs are not directly connected to the balance sheet of households, making it difficult to contribute to household wealth.

Certainly, SOEs play a critical role in national economic development, contributing through wages, taxes, and dividends to the state. The problem lies in the household sector's inability to directly experience the SOEs' contribution to their wealth improvement. Given that household consumption is deeply tied to households' wealth levels, the dividends and savings generated by SOEs fall short of effectively boosting household consumption. This is a key factor behind the low consumption rates in China.

Furthermore, the equity structure of many private enterprises in China, shaped by just over four decades of market reforms, remains highly concentrated. With consumption predominantly driven by the vast majority of ordinary consumers, the concentrated equity in private enterprises, held by a small minority, hardly brings a direct wealth effect to the broad mass of ordinary consumers, thus contributing to household consumption in a limited manner.

The two factors discussed—particularly the significant presence of SOEs in China—contribute to a diminished wealth effect between the corporate and household sectors. As a result, even though the corporate-savings-to-GDP ratio in China is relatively high, converting these savings into readily accessible wealth for households remains challenging. This necessitates the household sector to independently accrue substantial savings. Considerable savings in both the corporate sector and among households thus culminate in the exceptionally high total savings rate observed in the Chinese economy.

The Chinese market lacks coordinating power over consumption and investment

Ideally, the allocation of a nation's total income between consumption and investment should be governed by the return on investment (ROI). That is, the division of GDP into consumption and investment segments should be directed by the price signal, i.e., the ROI. When the ROI is high, the economy should lean towards higher investment and lower consumption; inversely, it should favor increased consumption over investment. Such a market-based mechanism is crucial for maintaining optimal investment and consumption proportions.

It's widely understood that households are the main drivers of consumption, whereas corporations primarily handle investments. During the primary distribution of national income, the share of wages allocated to households and capital returns to businesses tend to remain relatively stable, showing little fluctuation with changes in the return on capital (ROC). Thus, the ROC's impact on consumption and investment primarily comes into effect through secondary income distribution, notably through dividends from the corporate sector to the household sector.

When the ROI is high, enterprises should reduce dividend payouts to households, channeling more of their primary income into investment. Inversely, when the ROI is low, enterprises should increase dividends to households, facilitating more income transfer from the corporate to the household sector, resulting in reduced investment levels and higher household income and consumption. Essentially, the market adjustment of investment and consumption according to the ROI involves altering dividend distributions based on ROI changes. Without this mechanism, the balance between consumption and investment would veer off the optimal path.

For the above market adjustment mechanism to function, a key prerequisite is the majority of corporate equity being held by the household sector. This ownership allows households to influence corporate dividend policies and demand dividends when necessary. However, as I've previously explored regarding the high savings rate in China, there's a significant disconnect between the household and corporate sectors that hinders the effective operation of this adjustment mechanism.

This disconnect is further evidenced by data from China's Flow of Funds (FOF) Statements. Although the corporate-profits-to-GDP ratio in China has remained around 20% over the past two decades, the dividends the household sector receives from enterprises (including both state-owned and private) have never surpassed 0.5% of GDP, which is negligible. (Fig. 4)

Even though China faces issues of overinvestment and diminishing investment returns, which should necessitate reducing investment and boosting consumption, the obstructed flow of income from the corporate sector to households, as a result of insufficient dividends distribution, means that income earmarked for the corporate sector largely remains there. Corporate income inevitably becomes corporate savings and investment, keeping investment levels unsustainably high without adjustment according to ROI. This phenomenon is the main reason behind the excessive savings and overinvestment in China.

While microeconomic entities (including SOEs) do pay some attention to their ROI, with lower ROI potentially dampening their investment appetite, the broader picture is affected by the whole corporate sector's inability to efficiently reallocate its income to consumers via dividends. Consequently, corporations inevitably retain most of their savings. A lack of investment interest, compounded by the hindered flow of corporate savings to households, results in an economy where the savings scale outweighs the investment scale. Ultimately, this imbalance transforms excessive savings into a shortfall of domestic demand.