Over 5% Chinese women embrace life without children, surging in the 2010-2020 period

Motivations behind the soaring increase in lifetime childlessness in China reflects shifting family dynamics and life perspectives.

Amid growing concerns over declining population and fertility rates in China, here are some revealing and compelling numbers on the prevalence of lifetime childlessness among Chinese women:

Lifetime Childlessness: The rate of Chinese women without children by age 49 has reached 5.16%, reflecting a rise in lifetime childlessness.

Regional Variations: Cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, along with Northeast China, exhibit the highest childlessness levels, with fertility rates often below 1.0 children per woman. The disparity between urban and rural childlessness widened significantly from 2010 to 2020.

Age Groups: Childlessness remained stable among women born in the 1950s but soared to 7.85% for those born in the 1980s.

Education Levels: Since 2010, childlessness increased across all educational levels, with rates nearing 5% for lower education and up to 7.98% for higher education by age 49.

Marriage and Childbearing: There's a notable trend of delayed childbearing, especially among women aged 20-30, with up to 20% in cities like Beijing having their first child after 35.

Voluntary Childlessness: Surveys show that 9.5% of women born in the 1990s and 18.69% of women aged 20–39 in Shanghai have no intention of having children.

Written by He Yuchen, a Ph.D. student at the Center for Social Research, Peking University, the original Chinese article is also available on 婚姻家庭研究Marriage & Family Studies, the official WeChat blog from the Family Study Committee of the Chinese Sociological Association.

Following a summary of recently published research, He Yuchen's discussion on the motivations of lifetime childlessness also offers an interesting viewpoint. He approaches the topic with a refreshing openness, viewing the choice of childlessness not as a problem to be solved but as a valid lifestyle choice, indicating a shift towards accepting diverse life decisions.

Lifetime Childlessness among Chinese women: percentage and motivation

In traditional Chinese society, fertility was a significant aspect of a woman's identity, and a childless woman is often considered incomplete. A wife's inability to bear children could lead to discrimination and even justify divorce. However, the elevation of women's status and the decline of traditional family concepts have led to the decoupling of fertility from female identity. Both the concept of DINK (Dual Income, No Kids), representing childlessness within marriage and the outright rejection of marriage and childbearing have sparked widespread discussion in society. So, how many Chinese women remain childless for life? How has the level of childlessness changed? And what are the reasons behind this?

Percentage of lifetime childlessness among Chinese women and subgroups

In the context of the second demographic transition, characterized by increasing individualism and evolving perspectives on fertility, the prevalence of lifetime childlessness among women is witnessing a global increase. This trend is particularly pronounced in East Asia. For women in Generation X, the rates of lifetime childlessness were approximately 20% in South Korea and Taiwan. In Singapore, Japan, and Hong Kong, these figures approach 30%.

This essay will introduce two studies, which utilize long-form data from the Sixth (2010) and Seventh (2020) National Population Censuses of China to examine lifetime childlessness among Chinese women. For the purposes of their analysis, childlessness is defined as having no live births, with the understanding that biological children, as recorded in the census, may also encompass adopted children not officially reported. Neither did the two articles adjust their findings to account for mortality-related factors.

The authors of these two articles calculated the rate of childlessness by assessing the number of women without live births up to the age of 49. Zhang Cuiling et al. (2023), in their article "An Assessment of Lifetime Childlessness in China Based on the 7th Population Census," use data from the Seventh National Population Census to gauge overall rates of lifetime childlessness and explore variations among different groups of Chinese women. Chen Rong (2023), in her study "The Trend of Childlessness in Shanghai: The Relevance of the Second Demographic Transition Theory", focuses on lifetime childlessness among women in Shanghai and examines the relevance of the Second Demographic Transition Theory in this context.

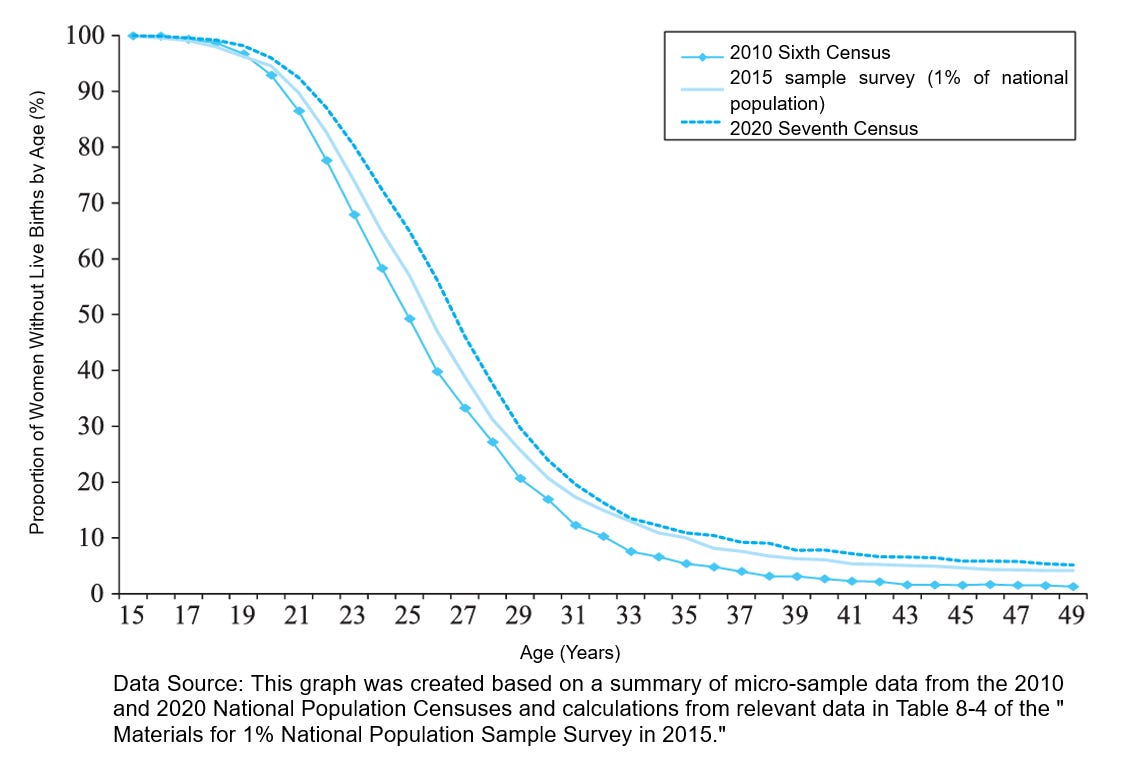

These studies show a general increase in the percentage of women across all age groups who have not had live births, with the figures doubling in magnitude. Specifically, the trend of postponed childbearing is most significant among women aged 20-30. Moreover, the percentage of women who have not given birth by the age of 49 has risen to 5.16%, which can be interpreted as an increase in lifetime childlessness within the country.

Across provinces, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Northeast China exhibit the highest rates of lifetime childlessness, with total fertility rates often falling below 1.0 children per woman. These regions are also characterized by a higher tendency for delayed childbearing, with up to 20% of women having their first child after the age of 35.

Examining cohort differences reveals minimal variation in lifetime childlessness rates among women born in the 1950s across provinces, with figures generally around 3%. However, as younger cohorts increasingly postpone childbearing, the percentage of lifetime childlessness is on the rise. For women born in the 1980s who are now reaching 40 years of age, the proportion without live births has escalated to 7.85%, marking a significant 5.27 percentage point increase compared to those born in the 1970s. Furthermore, the percentage of lifetime childlessness among women born in the 1970s and 80s has risen markedly when contrasted with those born in the 50s and 60s.

From an urban-rural perspective, the gap between urban (including prefectures and counties) and rural areas averaged 1.46 percentage points in 2010 but widened to an average of 3.34 points by 2020. In 2020, the percentage of lifetime childlessness among 49-year-old women in prefectures, counties, and villages was 6.29%, 5.50%, and 3.72%, respectively.

Additionally, a significant disparity exists among women residents with and without household registrations in large cities. For instance, in Shanghai, the percentage was 6.90% for registered women residents and 3.20% for non-registered women residents.

Since 2010, there has been a noticeable "stair-step" increase in the proportion of women without live births across different education levels. By 2020, the percentage of lifetime childlessness among 49-year-old women with primary and junior high school education approached 5%, while those with high school and higher education were at 6.46% and 7.98%, respectively. These trends indicate a shift in China from universal childbearing to a more diversified pattern of societal fertility, marked by clear social stratification in fertility trends.

The analyses indicate that the increasing tendency among women to opt for lifetime childlessness stems from an interplay of social and cultural factors on the macro scale. The acceleration of urbanization, postponed marriages, and childbearing, along with elevated levels of education, are collectively propelling this trend, which is expected to persist.

Personal motivations for lifetime childlessness

Zhang Cuiling et al. (2023) and Chen Rong (2023) also delve into the myriad factors contributing to the uptick in lifetime childlessness, encompassing both objective challenges such as infertility or delayed marriage and subsequent childbearing opportunities, and subjective preferences against parenthood.

From an objective standpoint, the prevalence of infertility in China is on the rise, and the prohibitive cost of treatment further restricts access to assisted reproductive technologies. Consequently, temporary infertility often becomes permanent, leading to an ongoing increase in the percentage of lifetime childlessness.

Subjectively, the rise in the voluntarily childless population is also significant, with more women making the conscious decision not to have children. A 2021 national survey showed that 9.5% of women born in the 1990s have no intention of having children, while a Shanghai-based survey found that 18.69% of female respondents aged 20–39 share this sentiment. This change reflects evolving family values and a growing preference for personal desires.

The growing percentage of voluntary childlessness has sparked intense debates, often attracting negative labels such as "selfish" or "shallow" to the childless. Despite such criticism, there's an expanding online dialogue about the potential physical impacts of childbirth on women, contributing to the emergence of terms like "childfree." This term signifies viewing childlessness as a form of personal freedom, some even taking pride in their decision and distinguishing themselves from those who choose to have children.

In an effort to explore the complex landscape of reproductive decisions, American author Meghan Daum compiled insights from 16 writers across varied generations, regions, races, and cultural backgrounds in her book Selfish, Shallow & Self-Absorbed. Through a collection of essays, these writers share their "fascinating, thrilling, and occasionally frustrating insight into the lives of the childfree."

Drawing on a quote from Anna Karenina, Daum encapsulates her findings by saying, "People who want children are all alike. People who don't want children don't want them in their own ways...For some, the necessary self-knowledge came after years of indecision. For others, the lack of desire to have or raise children felt hardwired from birth, almost like sexual orientation or gender identity. A few actively pursued parenthood before realizing they were chasing a dream that they'd mistaken for their own but that actually belonged to someone else—a partner, a family member, the culture at large."

Daum also describes her encounters with another nuanced perspective: individuals who said choosing not to have children was a totally legitimate and commendable choice but that they personally had been so enriched by parenthood that they genuinely thought that nonparents were living "incomplete, ultimately sad lives."

An interesting revelation from Daum's book is that opting out of parenthood doesn't correlate with greater psychological trauma or that they hate children. Quite the contrary, many childfree individuals actively engage in the lives of children within their extended families or communities, demonstrating a different form of nurturing and societal contribution. Despite the prevailing societal preference for parenthood, the book underlines that there are multiple pathways to leading a responsible, contributive, and fulfilling life. It argues for a society that not only supports and provides for those who wish to become parents but also respects and understands the decision to live childfree, acknowledging the diversity in paths to personal fulfillment and societal contribution.