Miao Yanliang: myth-busting the dollar hegemony, stablecoins, & multipolar monetary system

Former SAFE Chief Economist and current CICC Chief Strategist unpacks myths and realities of the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status and the rise of alternative systems.

Miao Yanliang joined China International Capital Corporation Limited (CICC) ,a leading investment bank, in March 2023 as Chief Strategist and Executive Head of the Research Department. Before that, he served for 10 years at the China State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), part of the People’s Bank of China, including as its Chief Economist since May 2018. He joined SAFE in 2013 as Senior Advisor to the Administrator and then Head of Research. Before SAFE, he was an economist with the IMF for five years. He holds a Ph.D., an M.A., and an M.P.A. from Princeton University.

Miao delivered a speech on May 30 at the National School of Development (NSD), Peking University, where he serves as an adjunct professor. The speech was published as a CICC report on June 8 and is also available on the official WeChat blog of CICC Research.

The article begins with a neat summary of the ten myths surrounding the “Triffin dilemma,” the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status, and the potential of a multipolar currency system, etc, followed by a detailed elaboration of each myth. So, I guess there is no need for me to restate the summary here. —Yuxuan Jia

国际货币体系的十个“未解之谜”

10 “Myths” Surrounding the International Monetary System

Abstract

The international monetary system is undergoing a profound transformation. The prolonged, unchecked expansion of U.S. public debt, the dollar’s “weaponisation” during the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and a series of policy shifts during the Trump 2.0 have steadily eroded confidence in the U.S. dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency. This structural shift is not only reshaping global trade and economic stability but also opening a historic window for reforming the international monetary order.

As the saying goes, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” We may be living through such a pivotal moment.

Yet a host of misconceptions—from deeply rooted conceptual errors to new confusions emerging from this era of profound changes—continue to cloud understanding of the international monetary system. This article identifies ten of the most representative “myths” that surround it. Analysing and clarifying these issues may not only gain a deeper understanding of the system’s workings and evolution, but also uncover valuable insights for advancing global governance.

Myth 1: Misinterpretation and misguidance of the “Triffin dilemma”

Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the “Triffin dilemma” has taken on two main interpretations: the “current account” version and the “safe assets” version. Both rest on misunderstandings: first, the mistaken belief that a country issuing a reserve currency must run a current account deficit; and second, the misleading claim that reserve currency status is inherently burdensome due to the deficits it supposedly requires.

Three key fallacies underlie this view: conflating net capital inflows with gross capital inflows; confusing “earned” foreign exchange reserves with “borrowed” ones; and failing to distinguish between bilateral and multilateral capital flows.

I believe that as long as large-scale outward investment is sustained—such that total capital outflows exceed inflows—a country can maintain a current account surplus while still serving as a global reserve currency issuer.

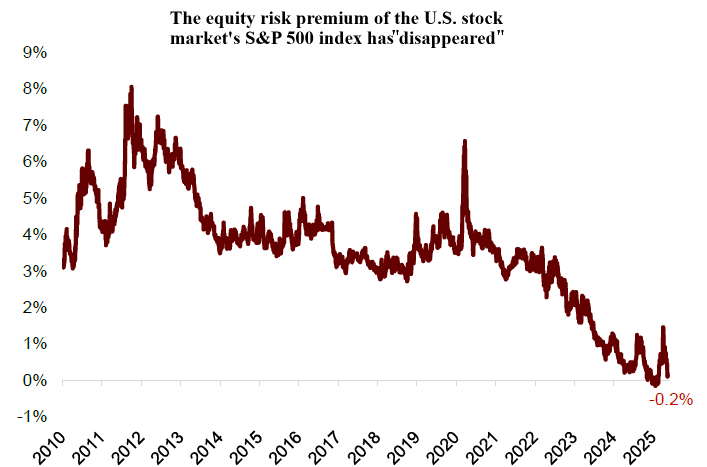

Myth 2: How did U.S. stocks become “safe assets”?

The waning foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries, alongside a large-scale rotation into U.S. equities, has driven the equity risk premium of the S&P 500 to nearly “disappear”, making U.S. stocks increasingly perceived as “safe assets.” This perception stems from both the decline in the safety of U.S. government bonds and the persistence of a long-term bull market in equities.

Underpinning this shift is the U.S. government’s use of its national balance sheet to repair private-sector balance sheets. While such interventions have bolstered prices and generated a sense of safety, they also harbour risks.

Myth 3: Will the U.S. voluntarily give up its reserve currency status?

The United States will not relinquish its reserve currency status and the many privileges it carries, particularly the substantial gains from international seigniorage. U.S. foreign assets are denominated in foreign currencies, while its liabilities are in dollars. Against the backdrop of a structural rise in U.S. net foreign debt, there is a strong incentive to devalue the dollar, thereby facilitating a global transfer payment to the U.S. to offset its current account deficit.

Myth 4: Why is the U.S. real economy’s global share declining while the dollar’s financial dominance is rising?

While the U.S. share of global real economic output has continued to decline, its international financial share is increasing. This is because offshore dollars remain the world’s primary funding currency, while onshore dollars serve as the global safe asset.

The global economy has increasingly shifted from real economic activities towards financialisation. Cross-border capital flows have expanded more rapidly than trade flows, further entrenching the dollar at the core of global finance.

Myth 5: Why does the U.S. dollar exhibit cyclical fluctuations?

The U.S. dollar exhibits cyclical characteristics across economic fundamentals, policy factors, and capital flows. It is also subject to two major positive feedback mechanisms operating at the real economy and financial levels.

First, dollar appreciation imposes relatively limited economic drag on the United States compared to other countries. Second, a stronger dollar attracts continued capital inflows. This feedback mechanism creates a self-fulfilling cycle, making the dollar cycle a long-term, large-scale phenomenon.

Myth 6: “Our dollar, your problem”

Although the United States is often the origin of global financial crises, non-U.S. economies typically bear the brunt of the impact. This arises from the misalignment and asymmetry between U.S. domestic policy objectives and their global spillovers, as well as from the dollar’s role as a global reserve currency, widely viewed as a safe haven, yet difficult to replace.

Dollar-related shocks—including shifts in Federal Reserve policy, trade frictions, and global risk sentiment—are amplified by structural changes in the global financial system. In response, it is essential for countries to establish effective macroprudential policy frameworks and maintain exchange rate flexibility.

Myth 7: Do we need an international monetary system?

A multipolar currency system is better than having no system at all, yet it still struggles to resolve issues of incoordination.

Myth 8: How can the world achieve a smooth transition from the dollar system to a multipolar currency system?

Building a multipolar currency system requires policy coordination and exchange rate flexibility among major currency-issuing economies. While the U.S. dollar remains the dominant currency for pricing, its role in trade settlement and international financing has shown signs of decline.

Two key obstacles that once constrained the internationalisation of the renminbi—high U.S. interest rates and persistent depreciation expectations during periods of trade tension—have begun to reverse. Going forward, leveraging China’s trade to promote renminbi internationalisation presents promising opportunities.

Myth 9: Will stablecoins strengthen dollar dominance?

Stablecoins maintain value stability through pegging mechanisms. Those pegged to the U.S. dollar could increase demand for dollar-denominated transactions and reinforce the dollar’s international role. However, if stablecoins evolve to reference a basket of currencies or are linked to alternative sovereign digital currencies, they could pose a challenge to the dollar’s reserve currency status. The broader impact of stablecoins on the global monetary order remains uncertain and warrants further exploration.

Myth 10: Can we return to the gold standard?

The notion that the gold standard is a “straitjacket” that causes deflation is a misconception. However, it does act as “golden handcuffs” that constrain the monetary policy flexibility of major economies. A return to the gold standard is highly improbable.

Myth 1: Misinterpretation and misguidance of the “Triffin dilemma”

In 1944, the Bretton Woods system was officially established, introducing a “dual peg” mechanism: the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce, while other member currencies were pegged to the dollar. This arrangement solidified the dollar’s central role as the international reserve currency.

Within this framework, in 1960, Yale economist Robert Triffin published Gold and the Dollar Crisis, in which he introduced the now-famous “Triffin dilemma.” He argued that if the United States sought to reduce its balance of payments deficit, the global supply of dollars would become insufficient to meet the world’s liquidity needs. Conversely, if the U.S. continued to run persistent deficits, the accumulation of overseas dollar claims would eventually far exceed the country’s gold reserves, undermining dollar convertibility. This paradox became known as the original “Triffin Dilemma 1.0.”

Under the gold standard, the original Triffin Dilemma 1.0 indeed held true: if the global liquidity of U.S. dollars as an international reserve currency exceeded the U.S. gold reserves, a dollar convertibility crisis would inevitably follow. However, after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1973, the world transitioned to a credit money regime, and Triffin 1.0 ceased to apply.

Nonetheless, as the United States began running persistent current account deficits from 1983 onward, scholars proposed an updated version—Triffin Dilemma 2.0—which has evolved into two main interpretations:

(1) The current account version

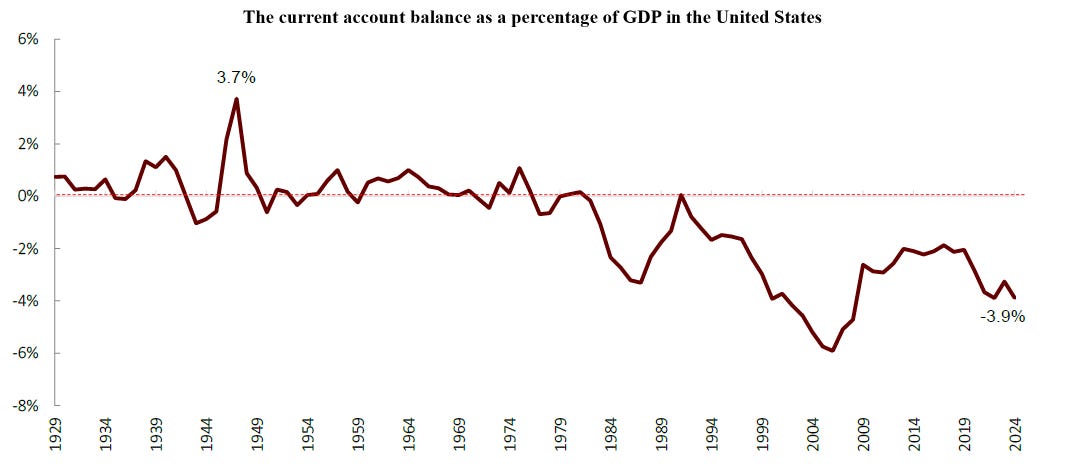

This version highlights the contradiction between the U.S. supplying global liquidity and the sustainability of its current account deficits. Since 1983, the U.S. has consistently run current account deficits, thereby injecting liquidity into the global economy. However, a reserve currency is expected to maintain long-term monetary value stability, which persistent current account deficits can compromise.

(2) The fiscal or “safe asset” version

This version focuses on the contradiction between supplying sufficient safe assets and maintaining U.S. fiscal sustainability. Given the dollar’s role as the global reserve currency, U.S. Treasuries are treated as the “safe asset.” As foreign central banks’ demand continues to grow, the U.S. faces a dilemma: issuing more Treasuries could weaken fiscal credibility, while issuing too few could lead to a global shortage of safe assets.

Be it “Triffin Dilemma 1.0” or “Triffin Dilemma 2.0,” the core issue lies in the tension between supplying global liquidity and maintaining the monetary value stability of the reserve currency.

If one concludes from this that the issuer of an international reserve currency must run persistent current account deficits to supply global liquidity, such an interpretation would be a misreading. There is no inherent link between dollar liquidity provision and the U.S. current account deficit. In fact, after the U.S. dollar became the world’s primary reserve currency in 1945, the United States maintained current account surpluses for nearly three decades.

Generally, there are three widespread misconceptions regarding the supply of dollar liquidity.

Misconception 1: Conflating net capital inflows with gross capital inflows.

According to the balance of payments identity, the sum of the current account balance (CA), the capital and financial account balance (KA), and changes in foreign exchange reserves (∆R) must equal zero: CA + KA + ∆R = 0

Assuming no intervention in the foreign exchange market (∆R = 0), a current account deficit must be matched by net capital inflows in the capital and financial account. These net inflows comprise both private and official sources.

However, reserve currency status refers specifically to the use of a country’s domestic currency in foreign official reserves—this corresponds to gross official capital inflows, not net official inflows.

If the domestic country experiences sustained official capital outflows (such as the U.S. Marshall Plan in the 1940s) or significant private capital outflows (as in the case of the UK under the gold standard, with heavy investments in overseas colonies), then even with substantial gross capital inflows linked to its reserve currency status, the capital and financial account could still record a net outflow. Consequently, this would be mirrored by a current account surplus.

Misconception 2: Confusing “earned” foreign exchange reserves with “borrowed” ones.

The accumulation of foreign exchange reserves can occur through multiple channels—not only via “earned” current account surpluses, but also through “borrowed” capital account inflows. For instance, when emerging economies face balance of payments crises, they often seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and a portion of the IMF’s lending is typically allocated to replenish the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

In fact, a country’s reserves can be “borrowed” not only from international institutions like the IMF, but also from bilateral partners (e.g., through central bank currency swap arrangements) or from international capital markets (e.g., by issuing dollar-denominated sovereign bonds).

Misconception 3: Failing to distinguish between bilateral and multilateral capital flows.

A country’s accumulation of dollar reserves does not necessarily depend on bilateral capital flows with the United States. These reserves can also originate from offshore dollar markets. In offshore dollar markets, such as the Eurodollar market in Europe, banks generate substantial dollar-denominated liabilities. As a result, the buildup of dollar reserves by a country may reflect not only U.S. current account or financial account deficits, but also credit creation in offshore markets.

This illustrates that even as the Triffin Dilemma enters its 2.0 stage, significant conceptual flaws remain, particularly in the current account version. At the core of this confusion is the oversimplified assumption that the U.S. trade deficit directly translates into the accumulation of reserve assets by foreign countries, and that dollar liquidity flows abroad only through U.S. current or capital account deficits. This is a misinterpretation.

Ultimately, dollar liquidity is a function of the banking system. As early as 1969, Milton Friedman noted in his analysis of the Eurodollar system that offshore dollars need not originate from U.S. trade deficits or capital outflows; they can also be created by offshore banks. To draw an analogy: this misunderstanding is akin to assuming that all onshore dollar liquidity comes solely from the Federal Reserve’s base money, while ignoring the role of commercial banks in money creation.

This conceptual error remains widespread and has even influenced discussions around the internationalisation of the renminbi. In reality, reserve currency status does not inherently require the domestic country to run a current account deficit. In promoting the renminbi internationalisation, China can definitely facilitate the accumulation of RMB-denominated reserve assets while maintaining broadly balanced external payments.

The Triffin dilemma not only suffers from widespread misinterpretation but has also been deliberately used for misguidance by the U.S. government. Stephen Miran, Trump's chief economic advisor, claimed that the Triffin dilemma arising from the dollar’s reserve currency status is the root cause of the persistent overvaluation of the dollar and the widening trade deficit, and has used this to provoke trade conflicts worldwide.

In fact, from the perspective of empirical econometrics, the reserve currency status has only a negligible impact on the dollar’s exchange rate and trade deficit. In other words, while it may lead to a slight overvaluation of the dollar and a modest expansion of deficits, it is by no means the decisive factor behind the United States’ persistent current account deficits. The true determining factors are the decline in the U.S. household savings rate and the increase in the fiscal deficit.

Myth 2: How did U.S. stocks become “safe assets”?

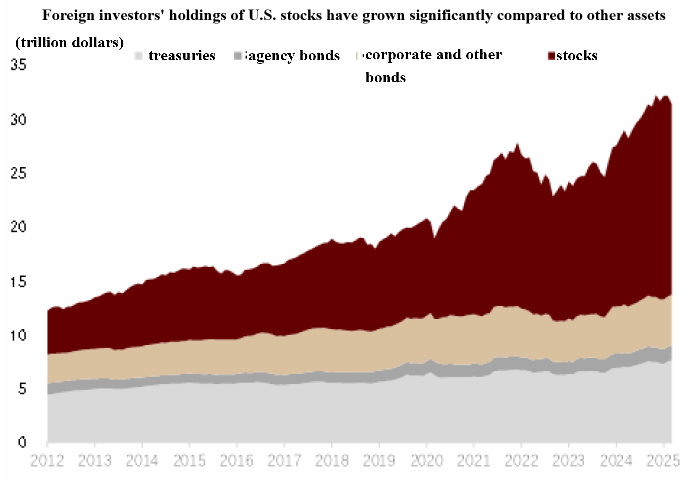

Traditionally, U.S. Treasury bonds have been regarded as the world’s primary safe-haven assets and the preferred choice for overseas investors seeking risk-off investments. However, in recent years, foreign holdings of long-term U.S. Treasuries have stabilised at around $7 trillion. At the same time, capital has increasingly flowed into U.S. equities, even driving the equity risk premium of the S&P 500 to nearly “disappear” by early 2025.

Under normal conditions, investors demand higher expected returns for holding risk assets like stocks compared to safe assets like government bonds. The apparent disappearance of the equity risk premium suggests that investors may now perceive U.S. equities as safe assets.

Why has this peculiar phenomenon emerged? There are two dimensions to consider: “push” and “pull.”

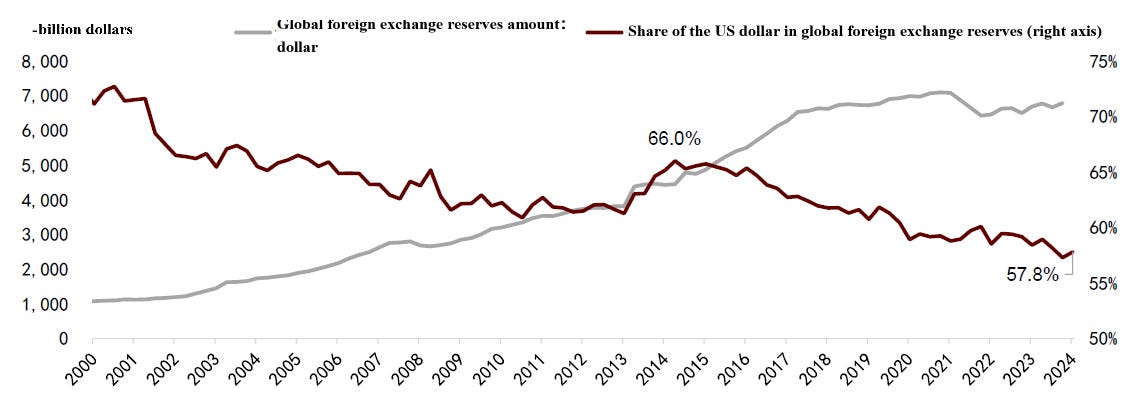

The “push” factor lies in the declining safety of U.S. Treasury bonds. America’s rivals, wary of the dollar’s “weaponisation” and the risk of asset freezes, have reduced their holdings of U.S. debt. As a result, the dollar’s share of global foreign exchange reserves has fallen from a peak of 66% in 2015 to 58% in 2023. Notably, since 2022, the absolute amount of dollar-denominated reserves has also declined.

America’s allies, though not necessarily concerned about asset freezes, are uneasy about America’s long-term solvency due to its expanding fiscal and current account deficits and rapidly deteriorating balance sheet.

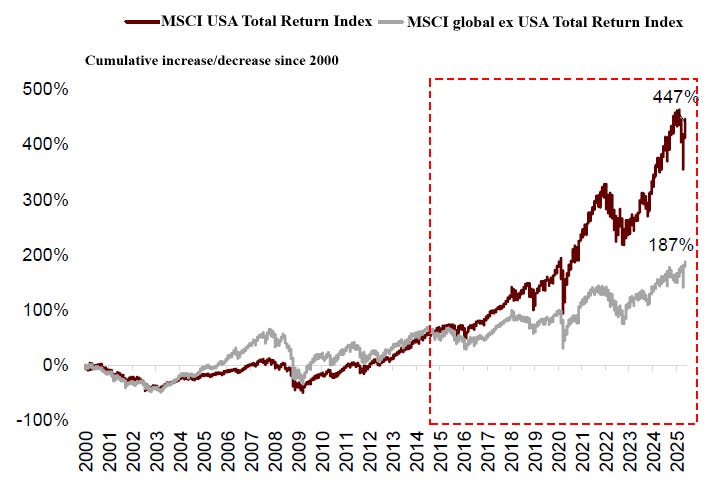

The “pull” factor is the stable, long-term bull market in U.S. equities, which has offered higher returns relative to other markets. Following the global financial crisis, massive overseas capital inflows, combined with the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing, drove up U.S. bond prices and pushed yields lower. In contrast, since 2015, U.S. equities have consistently delivered significantly higher returns than their international counterparts.

Since the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, the AI narrative has fuelled a powerful rally in the “Magnificent Seven” U.S. tech stocks, attracting substantial foreign investment into what some describe as America’s “AI myth.” This has created a positive feedback mechanism of capital inflows → rising equity prices → further inflows.

Foreign investors have continued to increase their holdings of U.S. equities, with their share rising from 26.7% in 2016 to 29.9% in 2024. As a consequence, U.S. net investment income from abroad has declined from a peak of nearly $100 billion in 2016 to zero.

This “seesaw effect” between U.S. Treasury bonds and equities reflects the U.S. government’s use of its national balance sheet to repair private sector balance sheets. Fiscal stimulus attracts capital inflows, and the wealth effect generated by rising asset prices reinforces expansionary fiscal policy, gradually strengthening the private sector’s balance sheets.

The shift from Treasuries to equities suggests that foreign investors perceive “two Americas”: one represented by a heavily indebted public sector, and the other by a dynamic and resilient private sector.

After President Trump announced “reciprocal tariffs,” the U.S. briefly experienced rising long-term interest rates and a weakening dollar, sparking concerns that the country was starting to look like an emerging market. In my view, bond yields are the key target of the Trump administration. It is the bond market—not the stock market—that ultimately limits the scope of his policy.

Myth 3: Will the U.S. voluntarily give up its reserve currency status?

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent believes the dollar’s reserve currency status is a heavy burden. Even if the United States were to voluntarily relinquish this role, no other country would be willing to assume it, leaving the dollar with no alternative but to continue in this role, reluctantly.

This echoes earlier remarks by Stephen Miran, Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers. However, Miran has recently reversed his position, denying that the United States would relinquish the dollar’s reserve currency status and even retracting his earlier proposal to tax foreign-held dollar assets.

I believe that the United States is unlikely to relinquish the dollar’s status as the international reserve currency, given that the substantial benefits far outweigh the associated cost. In academic literature, these advantages are often described as “dollar hegemony” or the “exorbitant privilege,” which can be summarised in four key dimensions:

First, the absence of currency mismatch allows the U.S. to conduct international trade without the need to hedge exchange rate risk. Second, the U.S. benefits from international seigniorage by issuing a currency that circulates globally. The depreciation of the dollar imposes a levy on more than half of the overseas dollar cash and demand deposits, a point that will be elaborated on later. Third, the U.S. can issue low-yield debt while investing in high-return assets, generating substantial net investment income. Fourth, dollars flowing out through trade deficits are often recycled back into the U.S. via financial account inflows. This finances the U.S. government and enterprises, supports the U.S. economy and equity markets, and offsets trade imbalances.

Next, turning to the second dimension of the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege,” how much seigniorage does the United States derive from the dollar’s role as the international reserve currency? It is important to distinguish between domestic and international seigniorage.

Domestic seigniorage refers to the revenue a government obtains from the private sector through currency issuance. International seigniorage, which is discussed here, refers to the revenue earned by the U.S. government and private sector from foreign entities.

According to estimates by Zhang Huaiqing, as of 2022, the United States earned approximately $60.3 billion in broad international seigniorage, equivalent to about 0.2% of U.S. GDP. This figure is broadly consistent with the estimates found in the literature of the 1990s. However, more recent studies have calculated higher levels of international seigniorage: by 2009, it was estimated at around 0.7% of GDP, and by 2012, the figure had risen to 1%.

The persistent increase in the estimated scale of U.S. international seigniorage can be attributed to the continuous expansion of its tax base under financial globalisation. Dollar seigniorage consists primarily of seigniorage from newly issued dollars, which constitutes nearly all of the revenue, and implicit seigniorage from inflation erosion—that is, the real value loss experienced by foreign holders of dollar-denominated assets (mainly cash and demand deposits) due to U.S. inflation.

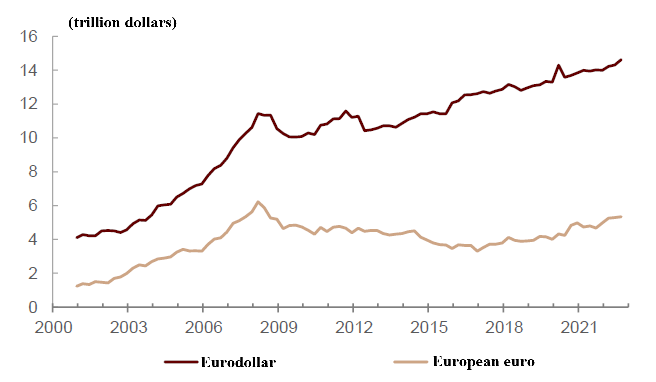

According to my estimates, as of 2023, the Eurodollar market totals approximately $16 trillion. Assuming a 4% inflation rate, the implicit seigniorage alone could imply over $600 billion annually, equivalent to more than 2% of U.S. GDP.

Of course, because offshore dollar markets also engage in credit creation, not all of these gains are captured by the U.S. government or the private sector. However, as Milton Friedman noted, ultimately, it is the U.S. banking system that supplies dollar liquidity, and the resulting gains flow back into American hands.

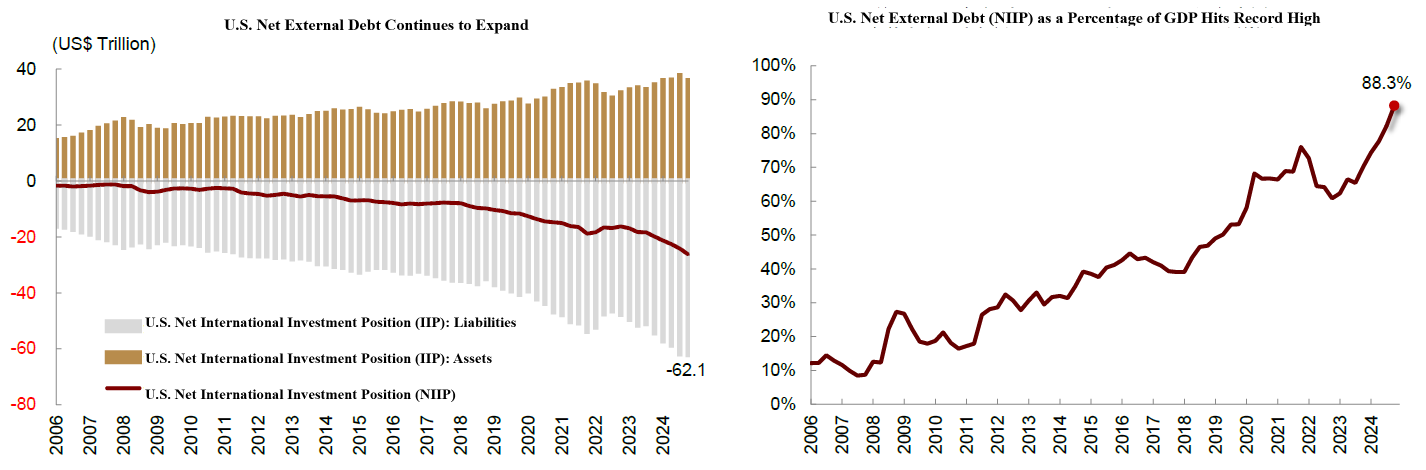

It is worth emphasising that one of the key advantages of the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status stems from the United States’ unique asset-liability structure. Over the past two decades, both U.S. external assets and liabilities have expanded significantly, with liabilities growing at a much faster pace.

From 2006 to the fourth quarter of 2024, U.S. gross external liabilities rose from $16 trillion to $62 trillion, while gross external assets increased from $14 trillion to $36 trillion. As a result, net external liabilities (assets minus liabilities) soared from less than $2 trillion to approximately $26 trillion, now representing 88.3% of U.S. GDP.

U.S. external assets are basically denominated in foreign currencies, while its external liabilities are denominated in U.S. dollars. This asymmetry allows the U.S. to reduce its net external liabilities by depreciating the dollar. In effect, this functions as an “international seigniorage tax”, transferring real wealth from the rest of the world to the United States.

Based on this structure, my rough estimates suggest that a 4.4% annual depreciation of the dollar would be sufficient to offset the U.S. current account deficit, which currently stands at 3.9% of GDP.

Given these dynamics, the United States will not relinquish the dollar’s reserve currency status. However, the continued deterioration of its net international investment position does create a strong incentive for dollar depreciation.

Myth 4: Why is the U.S. real economy’s global share declining while the dollar’s financial dominance is rising?

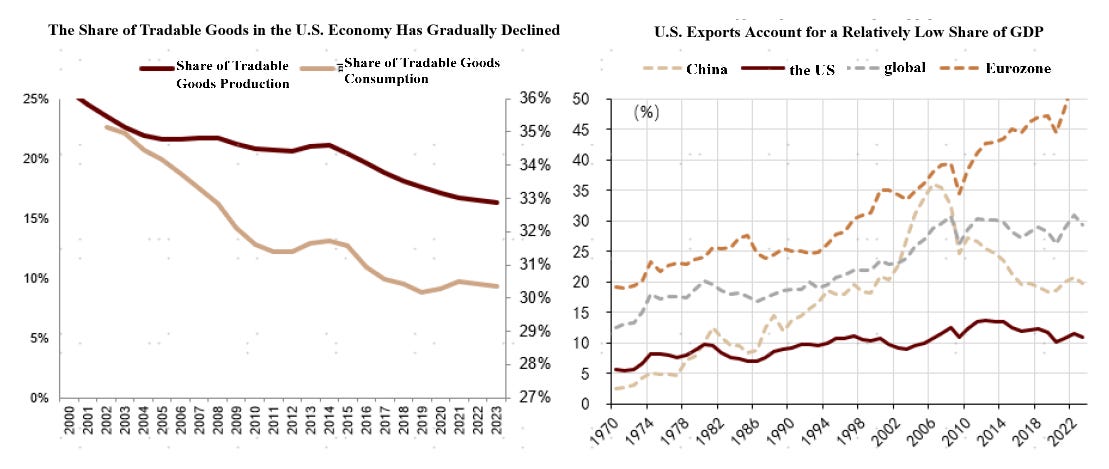

Although the U.S. nominal GDP share remains stable at around 25% of the global total, its share based on purchasing power parity (PPP) has declined steadily from 21% in 2000 to less than 15% in 2024. Meanwhile, its share of global trade has shrunk to approximately 12%.

Despite this continued decline in the U.S. share of the real economy, its role in international finance has instead expanded. The U.S. dollar’s share in SWIFT international payments has risen from 38% in 2011 to around 50% today. Although its share of global foreign exchange reserves has edged down slightly, it still stands at roughly 60%.

How can this divergence be explained? There are primarily two reasons.

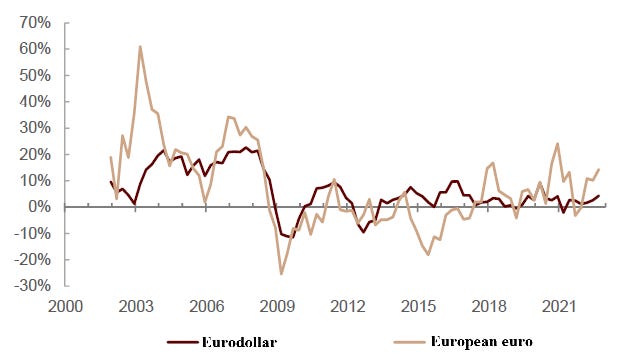

First, the offshore U.S. dollar remains the world’s most important funding currency. The offshore dollar market includes instruments such as Eurodollar and Eurodollar bonds. U.S. dollar funding currently accounts for approximately 60% of global offshore financing, with an outstanding volume of around $16 trillion.

Before the global financial crisis, the offshore euro market had expanded rapidly alongside the offshore dollar, once posing a potential challenge. However, following the crisis, demand for offshore dollars rebounded after a brief contraction, while offshore euro demand remained persistently weak. This divergence further cemented the dollar’s dominance as a global funding currency, leaving the euro far behind.

Second, the onshore U.S. dollar remains the world’s most crucial safe-haven asset. From a historical perspective, the role of the United States in the international financial system has undergone a major transformation.

Prior to 2000, the U.S. acted as a “global banker,” operating under a traditional model of “borrowing short and lending long”—raising short-term funds from foreign countries at low interest rates and issuing long-term loans to generate profits.

Since the early 21st century, the U.S. has increasingly assumed the role of a “global venture capitalist,” securing low-cost financing through instruments such as U.S. Treasury securities and investing in risky assets abroad to reap high yields.

U.S. Treasuries provide not only conventional financial returns but also non-monetary benefits, otherwise known as “convenience yield.” This unique value manifests in two primary ways: First, U.S. Treasuries possess exceptionally high market liquidity, allowing them to be converted into cash at any time. Second, U.S. Treasuries are widely accepted as high-quality collateral, making them highly valuable in a range of financial transactions.

These characteristics underpin strong and sustained global demand for U.S. assets, which in turn helps lower the United States’ cost of liabilities.

In summary, the financial dominance of the United States stems from two factors: the widespread preference for financing with dollars and the strong demand for U.S. Treasuries as investments. But this still does not fully explain why both U.S. assets and liabilities have grown so rapidly.

Here is a striking comparison: over the past two decades, while the global current account surplus as a share of GDP has remained relatively stable, and global trade has hovered around 30% of global GDP, the total stock of cross-border assets and liabilities has surged to approximately 300% of global GDP.

The growth of cross-border capital flows has far outpaced the expansion of global trade activities. This signals a fundamental transformation in the global economy—a shift from real economic activities towards financialisation.

So, where does this shift toward financialisation over real economic activities come from? A major driver is the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) policies and the rapid expansion of U.S. government debt.

As the Fed implemented successive rounds of QE and the supply of U.S. Treasuries surged, interest rates were pushed progressively lower. This excess liquidity fueled a global search for yield, amplifying the influence of liquidity over the real economy. Because the U.S. dollar functions as the world’s primary reserve currency, the Federal Reserve effectively plays a leading role in shaping global liquidity conditions.

The latest research highlights two key propositions: First, the global financial cycle is essentially a dollar cycle. Second, the dollar cycle is essentially a global risk appetite cycle.

These two propositions provide the foundation for a third critical question: What drives fluctuations in global risk appetite and shapes the level of risk premia? These drivers include long-term structural factors such as expectations of technological advancement and demographic ageing, as well as cyclical policy factors.

The combined effect of expansive fiscal and monetary easing in the United States has led to a sharp expansion in global liquidity that clearly outpaces the growth of the real economy. Moreover, because the U.S. dollar remains the world’s most important funding currency and U.S. Treasuries are the premier safe-haven asset, the financial dominance of the dollar has continued to strengthen, even as the U.S. share of global real economic output has declined.

Myth 5: Why does the U.S. dollar exhibit cyclical fluctuations?

The sustained rise of the U.S. dollar’s financial dominance has led to an increasing global reliance on dollar liquidity. Under such conditions, even countries with flexible exchange rate regimes find it difficult to insulate themselves from the influence of “dollar tide.”

The “dollar tide” refers to the cyclical flow of capital driven by the Federal Reserve’s policy, in which dollar liquidity flows outward from the United States and subsequently returns. Sustaining this system requires periodic fluctuations in the value of the dollar.

Regarding the dollar cycle, I have proposed a three-dimensional analytical framework that systematically examines the drivers of dollar exchange rate fluctuations across three key dimensions: 1. economic fundamentals (growth, exports and imports) 2. policy factors (fiscal and monetary policy) 3. capital flows (asset returns, cross-border capital flows)

However, in practical application, the relative influence of these dimensions varies over time. Therefore, it is crucial to identify which factor is dominant during different phases of the dollar cycle.

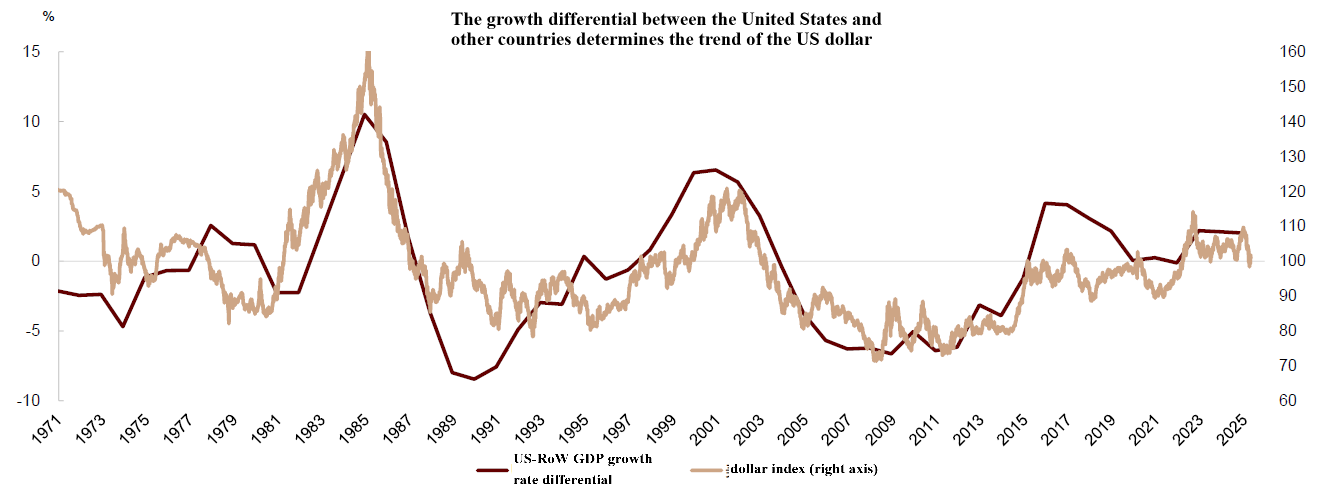

First, from the perspective of economic fundamentals, movements in the U.S. dollar exchange rate are ultimately anchored in the relative performance of the U.S. economy. When U.S. economic growth outpaces that of other major economies, the dollar tends to appreciate. In essence, the economic cycle underpins the dollar cycle.

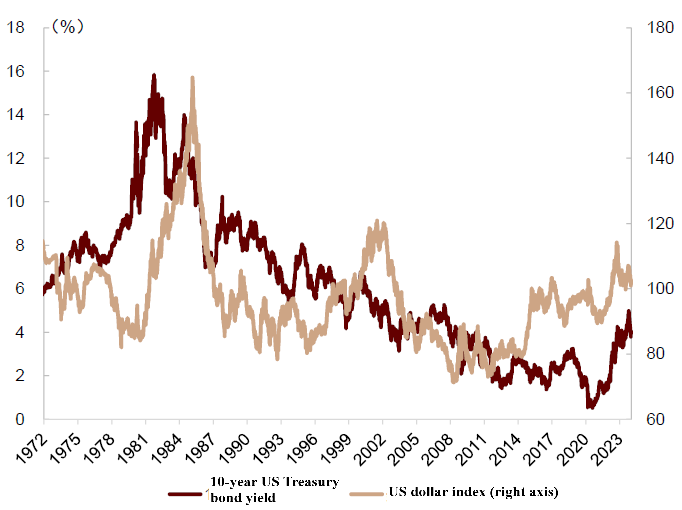

Secondly, from a policy perspective, movements in the U.S. dollar are significantly influenced by monetary policy by the Federal Reserve. Short-term capital flows, particularly those driven by arbitrage, are highly sensitive to deviations in short-term interest rates.

It is worth noting that if all central banks followed a uniform Taylor rule, then the policy dimension would seem redundant. However, in practice, the Fed’s policy decisions can be subject to errors and lags, so monetary policy does not always align with economic fundamentals.

When the Fed eventually shifts to a tightening stance (e.g. Paul Volcker’s contractionary monetary policy in 1979 or Jerome Powell’s aggressive rate hikes in 2022), the U.S. dollar still tends to strengthen. This occurs through two main channels:

1. Under the interest rate parity mechanism, a widening yield differential in favour of U.S. Treasuries triggers global capital reallocation; 2. The unwinding of carry trades accelerates dollar repatriation, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of dollar appreciation.

Therefore, policy divergence between the U.S. and other countries constitutes a second key driver of fluctuations in the dollar’s value.

Third, from a capital perspective, the drivers of U.S. dollar fluctuations are more complex. In addition to economic fundamentals and policy factors, global risk appetite and geopolitical dynamics have also become influencing factors.

In my contribution to the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) anthology commemorating the 50th anniversary of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, I argued that international capital flows are no longer entirely driven by economic fundamentals. Instead, “geopolitical proximity” has emerged as a new determinant of trade and capital flows.

Traditional gravity models in international trade theory primarily consider physical distance and economic size, but in today’s geopolitical environment, it is important to incorporate the geopolitical factor.

We used the similarity in voting patterns at the United Nations General Assembly to measure geopolitical proximity and found that capital flows began decoupling ahead of trade flows. For example, when China-U.S. trade tensions escalated in 2018, capital flows reacted sharply even before trade volumes showed significant changes.

However, geopolitical proximity is not static; it exhibits cyclical variation. After the United States imposed reciprocal tariffs under Trump 2.0, U.S.–Europe relations cooled rapidly, driving European capital to flow back to the continent. And the dollar, contrary to its historical pattern of strengthening during tariff shocks, actually weakened.

Overall, economic fundamentals, policy, and capital flows all exhibit cyclical dynamics, which underpin the cyclical fluctuations of the U.S. dollar exchange rate. Beyond these cyclical movements, the dollar cycle is also subject to amplification and overshooting, primarily driven by two positive feedback mechanisms.

The first is a real-economy positive feedback mechanism. The global impact of dollar appreciation is highly asymmetric: the U.S. dollar is the dominant currency for international credit, and many countries rely on dollar-denominated financing for production. A stronger dollar raises financing costs, compressing global manufacturing and trade, and placing downward pressure on non-U.S. economies.

Meanwhile, the U.S. economy is consumption-driven, with exports accounting for a much smaller share of GDP compared to the Eurozone or China. Moreover, the share of tradable goods in U.S. consumption and production has been declining steadily. Thus, while the dollar’s dominance in global finance continues to rise, the U.S.’s exposure to global economic activity is declining. This structural asymmetry means that dollar appreciation imposes relatively less economic pressure on the U.S. than on the rest of the world, creating structural asymmetry.

The second positive feedback mechanism operates through financial markets. When the U.S. dollar appreciates, the debt burden of other economies increases. This deterioration in balance sheets tightens financing conditions and triggers credit contraction. As a result, capital flows back into the U.S., reinforcing dollar strength.

At the same time, dollar appreciation attracts more capital back into the United States, pushing up asset prices. This generates a wealth effect, boosts market optimism, and draws in passive inflows and trend-following trades. The resulting additional capital inflows further elevate asset prices, reinforcing a self-perpetuating feedback mechanism.

In academic literature, this phenomenon is often referred to as self-fulfilling expectations, also known as George Soros’s theory of reflexivity. When investors expect dollar-denominated assets to appreciate, the expectations themselves trigger capital inflows that bring about the very appreciation, validating the original expectations. The dollar cycle is amplified when a large number of investors share the same expectations and act in unison.

Myth 6: “Our Dollar, Your Problem“

The above analysis of the dollar cycle suggests that the United States may strategically and persistently devalue its currency. History often repeats itself: while the U.S. has frequently been the source of global crises, it is other economies that bear the brunt of the impact. Will this time be any different?

In August 1971, President Nixon announced the suspension of the U.S. dollar’s convertibility into gold, triggering a sharp devaluation of the dollar. At the G10 meeting in Rome later that year, then-U.S. Treasury Secretary John Connally famously told European leaders: “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.”

As it turned out, the decoupling of the dollar from gold and the collapse of the Bretton Woods system did not weaken the dollar’s dominance.

In 1974, the United States successfully cemented the dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency and expanded its role in global pricing by signing the petrodollar agreement with Saudi Arabia, which shifted oil pricing from the British pound to the U.S. dollar. In contrast, by 1976, the United Kingdom was forced to seek assistance from the IMF due to overwhelming debt. In just 50 years, Britain went from being the leading reserve currency nation to the brink of bankruptcy.

In the second half of the 20th century, the rise of Japan’s economy posed a challenge to the United States, which was grappling with severe fiscal and current account deficits. Following the 1985 Plaza Accord, the U.S. dollar depreciated significantly, yet it was Japan that ended up mired in the “lost decades.”

Similarly, while the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis originated in the United States, its initial impact was felt by the UK’s Northern Rock, followed by French banks. The hardest-hit were Germany’s small and medium-sized banks, which had purchased U.S. subprime securities using pension funds. Ultimately, the crisis morphed into a sovereign debt crisis for Europe’s peripheral nations. Ironically, just as the euro appeared to present the most serious challenge to the dominance of the U.S. dollar, this American-born crisis left Europe crippled.

Why has the U.S. repeatedly managed to escape the worst consequences of global crises? Fundamentally, that’s because of the asymmetric impact of U.S. policy adjustments on its own economy versus non-U.S. Economies, which essentially reflects the various advantages that “dollar hegemony” provides to the U.S.

The first reason is “incoordination”. While the U.S. dollar serves as the global reserve currency, the Federal Reserve is not the global central bank. As the central bank of the U.S., the Fed’s policy decisions are solely focused on domestic economic conditions. However, these policies have significant implications for global liquidity. The Fed aims to ensure U.S. economic stability and is often willing to do so at the expense of financial stability and economic growth in other countries.

The second reason is “asymmetry.” The U.S. economic structure, which is predominantly driven by service consumption, reduces its exposure to global development risks. On the one hand, the U.S. is deeply integrated with the global economy through its capital markets and financial systems; on the other hand, it relies on its domestic service sector to, in some sense, isolate itself from the world economy. This structural shift not only makes the U.S. partially immune to global trade shocks but also reinforces the dollar’s upward cycle. Through a positive feedback mechanism between the real economy and financial channels, this asymmetry increases the vulnerability of other economies.

The third factor is “safe-haven” status. The dollar’s reserve currency role positions it as a safe asset, granting it a “convenience yield”. During normal periods, the U.S. can secure financing at relatively lower costs. In times of crisis, global capital tends to flee risk assets and rush into U.S. Treasuries (a flight-to-safety), which allows the U.S. to implement fiscal stimulus at even lower costs, without facing immediate debt repayment pressures. This occurs because, as long as the U.S. nominal interest rate (r) remains lower than its nominal economic growth rate (g), the debt-to-GDP ratio can stabilise or even decline despite fiscal deficits, making U.S. debt sustainable.

Finally, the most critical reason the U.S. dollar has maintained its relative advantage over the long term is that it is “hard to replace.” Despite the risks of weaponisation and strategic devaluation, there is currently no viable alternative to the dollar as the global reserve currency—there is no alternative, or TINA. Some have voiced their frustration, asking, “How many more mistakes must the dollar make before the world stops forgiving it?” This sentiment stems from the fact that America’s major competitors—such as Japan in the 1990s and Europe in the 2010s—have faced significant structural issues and policy missteps. In contrast, the Federal Reserve’s policy independence and the corrective mechanisms offered by its developed financial markets have allowed the U.S. to avoid many of these errors.

The above discussion highlights the asymmetric shocks caused by U.S. dollar cycle adjustments to both the U.S. and other countries. How are these asymmetric shocks transmitted and realised? This begins with the “dollar tide,” which originates from U.S. monetary easing. Many worry whether U.S. monetary easing is an attempt to gain an unfair advantage. Under a fixed exchange rate system, the U.S. could only impose seigniorage. However, under a floating exchange rate system, the U.S. can influence global capital flows, creating cyclical tides of dollar appreciation and depreciation.

The first mechanism is the impact of the Federal Reserve’s policy shifts. The U.S. first implements loose monetary policies, driving up asset prices, and then shifts to tightening. This “loose-tight” policy manoeuvre often triggers severe fluctuations in asset prices in other countries. This was particularly evident during the 2013 “Taper Tantrum”, when even a mere mention by then-Chairman Ben Bernanke of potentially scaling back bond purchases caused significant turmoil in emerging markets.

The second mechanism is trade friction. During periods of significant monetary easing in the United States, global imbalances in international payments accumulate, with the U.S. trade deficit widening and the trade surpluses of other countries rising passively. While an increase in trade surpluses is generally positive, it can trigger trade friction and its ripple effects. If the U.S. leverages this situation to pressure other countries into currency appreciation, improper handling can lead to profound long-term consequences, as seen with Japan in the 1980s and Europe in the 2000s.

However, the most influential factor remains the risk sentiment shock. This explains why certain countries, despite having limited trade and financial ties to the U.S., still suffer significant impacts. The global financial cycle is essentially a dollar cycle, and the dollar cycle is essentially a risk appetite cycle.

Shifts in risk appetite are closely tied to changes in the Federal Reserve’s policies. When the U.S. adopts substantial monetary easing, it tends to increase global risk appetite, driving up asset prices. Conversely, when the Fed tightens its policies, market risk aversion rises, leading to the depreciation of non-dollar currencies and the bursting of asset bubbles.

The structural changes in global financial markets have further intensified the dollar tide. After the financial crisis, asset managers have replaced banks as key intermediaries in financing. The traditional banking-dominated financial system, characterised by long-duration loans and slow adjustments, has been gradually supplanted by a new financial system centred around investment banks and asset management firms, which exhibit stronger risk appetites and faster adjustment capabilities.

These new financial institutions rapidly increase leverage during economic upswings and deleverage just as quickly during downturns. As a result, risk sentiment has become a crucial driver behind abrupt shifts in capital flows, with its significance continuing to grow.

In summary, the reason the U.S. dollar consistently emerges unscathed, or even stronger, after significant fluctuations is not due to the dollar’s depreciation itself, but rather the asymmetric impact of the dollar tides on other countries through financial, trade, and risk appetite channels. This dynamic serves to consolidate or even enhance the dollar’s dominant position.

How can other nations cope with the spillover effects of U.S. monetary easing? The key lies in formulating sound domestic policies and avoiding major policy missteps. Japan’s economic troubles were not caused by the Plaza Accord, but by a serious misjudgment of its own potential growth rate, which led to excessive monetary easing and the inflation of asset bubbles. In contrast, Europe found itself in a passive position due to delayed policy responses.

I believe that the policy response should primarily address two key aspects: first, establishing an effective macroprudential policy framework to mitigate the shocks from cross-border capital flows, and second, implementing a floating exchange rate regime to alleviate pressure through price adjustments.

However, while a floating exchange rate may seem straightforward in theory, its implementation is more challenging in practice. It requires not only a broad consensus but, more importantly, confidence in the market’s adjustment mechanism. When the RMB depreciates, concerns arise over potential capital outflows; when the RMB appreciates, there are fears of negative impacts on export-driven industries. Neither appreciation nor depreciation satisfies all stakeholders, making exchange rate stability seem like the most acceptable compromise. However, maintaining a rigid exchange rate is the most difficult option. It’s like riding a bicycle: only through movement can dynamic equilibrium be achieved.

In essence, under a fixed exchange rate regime, risks such as currency and maturity mismatches do not disappear; rather, they become concentrated on the national balance sheet. In contrast, under a floating exchange rate, these risks are distributed to micro-level market participants. Ultimately, with floating exchange rates, as Franklin D. Roosevelt once said, “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Myth 7: Do we need an international monetary system?

Unlike in the past, the United States now seems to be actively shirking its responsibilities within the international monetary system, even tending to “forcibly dismantle” the existing framework. Such behaviour is exceedingly rare in the history of international finance. Does it imply that we no longer need an international monetary system?

Objectively speaking, China, as the world’s largest trading nation, has benefited from the current international monetary system. Any country with robust manufacturing capabilities has a vested interest in supporting globalisation. Historically, both Britain and the United States, when at the peak of their manufacturing prowess, were the primary drivers of globalisation.

Global trade and capital flows inherently require a central currency. The existence of a central currency provides economies of scale for the foreign exchange market, reducing transaction costs and currency hedging expenses. Without the U.S. dollar serving as the central currency, the 180 currencies recognised by UN member states would create over 16,000 possible currency pairs (calculated by N × (N-1)/2), resulting in significantly lower trading efficiency. By adopting a universal central currency, the problem is simplified to just 179 currency pairs (N-1), effectively reducing complexity by 99%. As the world’s most widely recognised reserve currency, the U.S. dollar assumes the role of the central currency.

The global landscape is evolving towards multipolarisation, a trend reflected by the restructuring and diversification of global supply chains. This presents a historic opportunity for the internationalisation of the renminbi. However, it is crucial to remain vigilant, as the absence of a unified system and a “keep our own house in order” approach could lead to severe negative spillover effects. These may include competitive devaluations, asset-liability mismatches and currency mismatches driven by imbalanced risk appetite, as well as sharp capital flows and significant exchange rate fluctuations.

Therefore, a multipolar currency system may be better than having “no system” at all. A multipolar currency system fosters currency competition, which not only constrains dollar hegemony but also provides room for emerging currencies to develop. The inclusion of the renminbi in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket is a case in point: its five-year review mechanism and the “freely usable” criterion serve as effective external discipline. However, despite these advantages, a multipolar currency system still falls short of resolving the incoordination within the international monetary system and thus requires further innovation.

Myth 8: How can the world achieve a smooth transition from the dollar system to a multipolar currency system?

The international monetary system is transforming from a unipolar, dollar-dominated regime to a multipolar one. Academic views differ on how a multipolar currency system can operate stably. For instance, Barry Eichengreen’s research, drawing on the 1914–1939 period, when the British pound and U.S. dollar jointly dominated, suggests that a multipolar currency system is not necessarily unstable.

This raises the question: how many poles make for the most stable system? A 2019 study by Professor He Zhiguo finds that a bipolar monetary system is inherently unstable, as even small shocks (e.g., fiscal deterioration in one country) can trigger a coordinated shift by investors to the other, causing the collapse of the original safe asset status.

Similarly, Professor Markus Brunnermeier argues that bipolar systems are prone to conflicts, and instead proposes a five-pole system as more balanced. Although this hypothesis still requires empirical validation, it underscores the need for policy coordination among major currency issuers, institutional constraints on policies of reserve currency issuers, and the maintenance of floating exchange rate regimes among key currencies to support a stable transition to a multipolar currency system.

The international monetary system has fragmented since the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and this restructuring is accelerating under the second Trump administration. International currencies generally serve three core functions: store of value, unit of account, and medium of exchange. These functions are closely interrelated and exhibit strong network effects, granting early movers a deeply entrenched advantage.

However, the Russia-Ukraine conflict and reciprocal tariffs have accelerated the decoupling of these three functions. While the U.S. dollar remains the dominant unit of account for pricing, alternative currencies are increasingly being used for trade, settlement, and even financing. These shifts signal an incremental weakening of dollar hegemony.

Importantly, this disruption is transmitted not only through trade channels but also by elevating the risk premium on dollar-denominated assets and increasing global uncertainty.

Objectively speaking, while global confidence in the U.S. dollar has recently wavered, its ability to maintain reserve currency status ultimately depends on two key factors: first, whether the United States can continue to lead the technological revolution; and second, whether it can preserve the advantages of its financial system, such as the Federal Reserve’s independence and the self-regulating and corrective capabilities of its financial markets.

Before these two factors are confirmed, the fragmentation of the international monetary system presents a historic opportunity for the renminbi to expand its role in payment settlement and as a store of value. The two major headwinds that once hindered renminbi internationalisation have now reversed. First, while the renminbi was once a high-interest currency and the U.S. dollar a low-interest one, the roles have now reversed: the renminbi is now a low-interest currency, while the U.S. dollar is high-interest. This shift could significantly enhance the renminbi’s role in financing. Second, renminbi holdings were often negatively impacted by depreciation expectations, particularly during the trade tensions of Trump’s first term. In contrast, the Trump 2.0 tariffs on all countries have contributed to the appreciation of the renminbi.

As the saying goes, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” The renminbi should seize the opportunity presented by the overseas expansion of Chinese enterprises and production capacity to boost its cross-border circulation. By leveraging China’s manufacturing strengths in sectors such as machinery, electronics, and new energy equipment, the renminbi can encourage other countries to use it for trade settlement, thereby creating a self-sustaining cycle of renminbi reflow driven by real trade demand.

Myth 9: Will stablecoins strengthen dollar dominance?

Stablecoins combine the functional advantages of traditional reserve currencies while mitigating the major drawbacks of Bitcoin. Due to its extreme price volatility, Bitcoin struggles to fulfil the basic functions of money. It cannot reliably serve as a unit of account, medium of exchange, or standard for pricing, and is essentially limited to being a specialised asset. In contrast, stablecoins maintain value stability through anchoring mechanisms, making them more suitable for fulfilling the full range of monetary functions.

Recently, both the United States and Hong Kong have been accelerating legislation on stablecoins, which warrants close attention. Dollar-pegged stablecoins, in particular, have the potential to increase demand for U.S. dollar transactions and reinforce the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency.

Unlike payment systems provided by U.S. companies such as PayPal, dollar-pegged stablecoins operate as independent vehicles for dollar-denominated assets, circulating globally on-chain without relying on U.S. companies or the U.S. banking system. They essentially function as “portable digital dollar bank accounts” that do not require American involvement, offering a global financial infrastructure for convenient dollar usage. This could further expand the dollar’s reach in the global economy and solidify its reserve currency status.

Simultaneously, other countries can issue stablecoins, which may not necessarily be pegged to the U.S. dollar. If these stablecoins are pegged to a basket of currencies (such as the IMF’s SDRs) or other countries’ sovereign digital currencies, they could pose a further challenge to the dollar’s reserve currency status. The impact of stablecoin development on the dollar remains an area requiring further research and exploration.

Myth 10: Can we return to the gold standard?

Some argue that the United States may eventually relinquish its dominant position in the international monetary system, while the euro is unable to take over due to the lack of unified fiscal backing. In the absence of alternatives, some advocate for a return to the gold standard. This view is seemingly supported by the ongoing gold purchases by multiple central banks.

However, I believe the gold standard is unlikely to be restored. The conventional view holds that the gold standard inevitably leads to deflation, likening it to putting a child into a fixed-size “straitjacket” that eventually becomes too tight as the economy grows. This analogy, however, is misleading.

In the gold standard era, gold only backed the issuance of base money, while the supply of liquidity primarily depended on broad money created by commercial banks through the fractional reserve banking system. Even during the classical gold standard period, the gold backing ratio steadily declined. For instance, the British pound’s gold backing fell from an initial 40% to just 2–3% by the time the pound left the gold standard, often described as “little more than a thin gold veil.”

More accurately, the fundamental constraint of the gold standard was not on the money supply, but its requirement for member countries to prioritise external balance over domestic objectives. In other words, countries under the gold standard had to prioritise maintaining exchange rate stability over employment or other internal policy goals. Therefore, for major countries, the gold standard, much like any fixed exchange rate regime, acted as a “golden handcuff,” limiting the flexibility of monetary policy.

In terms of renminbi, achieving reserve currency status requires advancing and refining the floating exchange rate regime to facilitate international holdings. Without full liberalisation of the capital account, promoting renminbi internationalisation necessitates coordination between the onshore and offshore markets. If a clean float cannot be achieved, maintaining currency stability would entail either raising interest rates, leading to significant volatility in the prices of offshore renminbi financial products, or restricting liquidity, which would hinder the development of the offshore market.

Essentially, although this paper discusses monetary phenomena, the status of an international reserve currency should perhaps not be viewed merely as a monetary issue but rather as a dynamic process tied to national competitiveness. Due to usage inertia and network effects, changes in currency status often lag behind shifts in actual competitiveness. By 1900, the U.S. economy had already surpassed Britain in size, yet it was not until 1945 that the dollar replaced the pound as the world’s reserve currency, and not until the 1970s that the petrodollar system was leveraged to establish a dollar-dominated pricing framework.

Currently, China’s nominal GDP, calculated at market exchange rates, accounts for 64% of that of the United States, while its GDP based on purchasing power parity (PPP) has already surpassed that of the U.S. Based on this historical trend, if the 20th century could be called the “Dollar Century,” then the 21st century may well become the “Renminbi Century.” The key driver of this transformation lies not in the policy choices of the Trump administration but in China’s own strategic decisions and policy implementation.

Thanks for busting those myths!

This is an outstanding identification of the issues - eg. why is the U.S. real economy’s global share declining while the dollar’s financial dominance is rising? But the author underestimates the dominance of the dollar in global capital markets which is multiple times the size and depth relative to global trade. The author also identifies correctly the financialization of the U.S. economy but does not understand that ALL economies eventually financialize - including China’s and soon China will be begging for foreign investors to buy its debt. The part about the potential decline of the dollar being an opportunity for the renminbi to internationalise begs the question - for what purpose? But I must say that while the writer gives the best context I have seen so far for discussing the future of the U.S. economy, it does make me wonder why the subject of his analysis and his conclusions are tangential to each other. What is the purpose, for example, of asking if a country with a current account surplus can also be a reserve currency? Unless that question was meant for China, because the U.S. suffers a chronic current account deficit, and the answer really is that China can have its cake and eat it. Here is where the authors line of thought unravels, but still, the core analysis on the U.S. was pretty good and accurate.