Miao Yanliang explains China's large monetary injection yet blocked transmission

Former SAFE Chief Economist and current CICC Chief Strategist says fiscal-monetary coordination is key to ending China’s “whack-a-mole” problem of ample funding but scarce market liquidity.

Miao Yanliang joined China International Capital Corporation Limited (CICC) ,a leading investment bank, in March 2023 as Chief Strategist and Executive Head of the Research Department. Before that, he served for 10 years at the China State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), part of the People’s Bank of China, including as its Chief Economist since May 2018. He joined SAFE in 2013 as Senior Advisor to the Administrator and then Head of Research. Before SAFE, he was an economist with the IMF for five years. He holds a Ph.D., an M.A., and an M.P.A. from Princeton University.

By examining structural shifts in the money supply, Miao seeks to reveal the key frictions impeding economic activity and weakening the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Specifically, he identifies three major structural imbalances:

1. Excess of time deposits vs. shortage of demand deposits. Economic uncertainty, prolonged low interest rates, and idle circulation of funds have driven savers toward higher-yielding, longer-term deposits.

2. Disproportionate share of household deposits vs. insufficient corporate deposits. Weakened housing demand has disrupted the traditional channel through which household deposits transformed into corporate deposits via the real estate market.

3. Rise in deposits from non-bank financial institutions vs. decline in deposits from the real economy. Following the crackdown on unauthorised interest rate adjustments, falling deposit rates prompted businesses to shift funds into higher-yielding products offered by non-bank institutions. In response, banks raised interbank deposit rates, hurting their own profitability.

Miao advocates for greater fiscal-monetary coordination in China’s economic strategy. He calls for the development of specialised monetary tools to direct funding toward sectors closely linked to household spending, such as childbirth, elder care, tourism, and education. Additionally, he recommends targeted tax cuts and subsidies for low-income groups, an increase in the personal income tax threshold, and greater public infrastructure investment. To stabilise the ailing real estate market, Miao also stresses the need for new models of state-backed acquisition of distressed property assets and capital injections.

Miao has kindly reviewed this translation of his speech, delivered at the March 2025 monthly meeting of the China Macroeconomy Forum (CMF), a think tank affiliated with Renmin University of China. The original text is available on the CMF’s official WeChat blog.

缪延亮:从广义货币结构看货币传导效率

Miao Yanliang: Analysing the Efficiency of Monetary Policy Transmission from the M2 Structure

Among various macroeconomic indicators, financial data stand out for their timeliness and credibility. Evolution of the overall size and structure of financial data not only reflects how effectively monetary policy is transmitted to the real economy but also helps pinpoint bottlenecks in economic operations. In recent years, although China’s M2 money supply has steadily increased, inflation has remained subdued. Private enterprises continue to face financing difficulties marked by high costs and restricted access, highlighting a conflict between an “abundant total money supply vs. structural imbalance”. A portion of liquidity remains confined within the financial system, failing to reach the real economy. Analysing the structural shifts and imbalances within the M2 can illuminate both the transmission pathways of monetary policy and the constraints that impede economic efficacy.

There are three major structural imbalances within the M2:

1. An excess of time deposits and a shortage of demand deposits;

2. A disproportionate share of household deposits and insufficient corporate deposits;

3. A rise in deposits from non-bank financial institutions and a decline in deposits from the real economy.

The underlying cause of these imbalances is the relatively low expected return on investment in the real economy. Consequently, funds are increasingly concentrated within the financial system, searching for yield. This impedes the conversion of funding liquidity into market liquidity, thereby obstructing the transmission of monetary policy.

The core bottleneck here is weak household consumption, which disrupts the internal circulation of income between households and enterprises in the real economy. This is reflected in financial markets by the persistent accumulation of household deposits, while corporate deposits face an unprecedented decline.

The increase in interbank deposits and the corresponding decrease in real economy deposits stem from the dynamics of a low-interest-rate environment. No matter how expansive monetary policy becomes, capital struggles to reach the real economy. Instead, it circulates within the financial system, shifting between household deposits, wealth management products, and interbank placements, creating a self-perpetuating arbitrage cycle akin to a “whack-a-mole” game.

Money is just a symptom of the issue. In the context of weak aggregate demand, simply relying on monetary policy is insufficient to resolve the blockage in monetary policy transmission. Fiscal policy collaboration is necessary. The key lies in boosting household consumption and ensuring a smooth flow of funds between businesses and households. This would raise expected returns in the real economy and prevent idle capital within the financial system or, worse, disintermediation and capital flowback into the financial sector.

Since 2025, China’s capital markets have shown signs of recovery, and transactional demand for money has begun to rebound. At this critical juncture, preserving money supply elasticity is essential. Measures such as reserve requirement ratio (RRR) cuts and interest rate reductions should be employed at appropriate times to alleviate liability pressures on banks.

1. Large Monetary Injection but Blocked Transmission

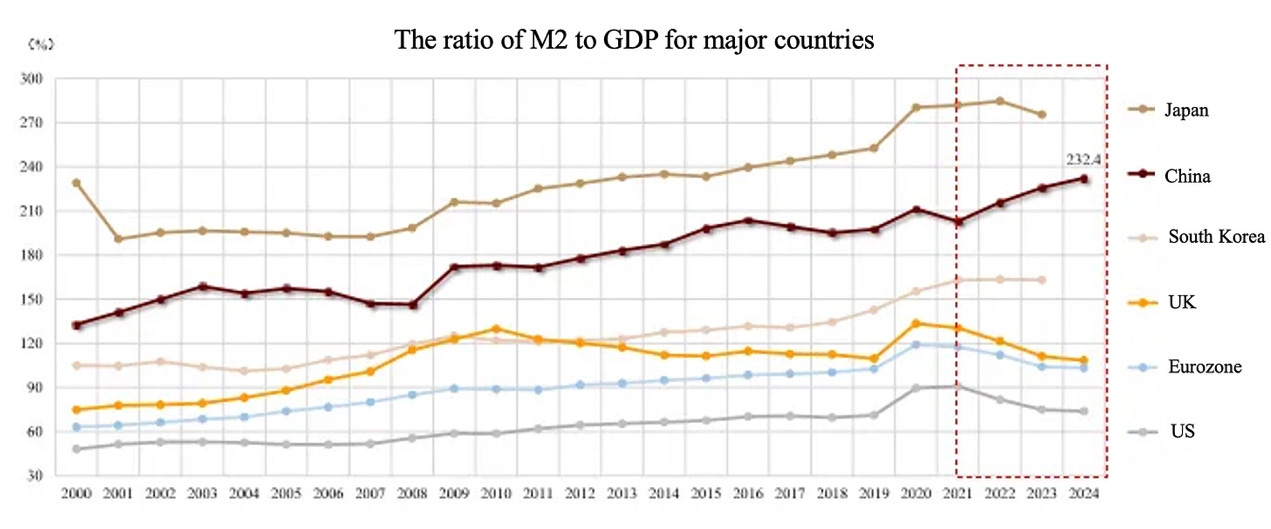

From an aggregate perspective, China’s M2-to-GDP ratio is relatively high compared to other major global economies. As of February 2025, China’s M2 (broad money supply) had reached nearly 321 trillion yuan, with the M2-to-GDP ratio standing at 232%, second only to Japan. While the statistical definitions of M2 may differ across countries, making direct comparisons potentially misleading, the trend in the M2-to-GDP ratio is telling. After the pandemic, most developed economies have experienced a contraction in their money supply relative to GDP. In contrast, China’s M2-to-GDP ratio has been steadily rising since 2021, signalling consistent monetary expansion within the country.

According to the Quantity Equation of Money (MV = PY), assuming all other variables remain constant, an increase in M (money supply) should lead to a corresponding rise in P (price level). However, in reality, despite China’s faster money supply growth compared to developed economies, inflation has remained lower than in these countries. This indicates a decline in V (velocity of circulation), which is limiting the effective transmission of monetary policy.

At the same time, despite the substantial injection of money supply, financing costs for private enterprises remain relatively high. The interest rates charged by private microfinance lenders have been on a rising trend since 2021, reaching 20% in February 2025, nearing the historical peak of 20.4% in mid-2024. This highlights a clear segmentation in the transmission of monetary liquidity.

2. Three New Structural Changes in Money Supply

Analysing the structural changes in M2 and understanding their underlying causes can help reveal the blockages in monetary policy transmission. Three key structural changes or imbalances within M2 are highlighted below.

The first structural change is an excess of time deposits relative to demand deposits, as reflected in the widening “scissors gap” between M1 and M2 growth rates from January to September 2024.

In September 2024, this gap reached a historic high of 10.1%. Since M1 represents demand deposits and M2 includes both demand and time deposits, the widening of the “scissors gap” suggests a trend toward an increasing share of time deposits.

In sectoral terms, the proportion of demand deposits within total deposits has been declining across households, enterprises, and even government agencies. For both households and enterprises, the share of demand deposits has fallen below 30%, reaching a historic low. In my January 2024 article, “From Inefficient Monetary Expansion to Efficient Credit Expansion,” I argued that, due to credit expansion targets and relatively high deposit rates, money from various sectors eventually flowed into time deposits, which offer the highest yields. This created a feedback loop of idle funds: large banks lend to enterprises, enterprises deposit in small banks, and small banks buy bonds, which further drove M2 growth.

Following the crackdown in April 2024 on banks’ improper use of manual interest rate adjustments—where higher, unapproved rates were offered by circumventing internal controls and regulatory oversight to attract deposits—bank deposit rates were subsequently reduced through multiple rounds of adjustments. Combined with repeated warnings from the People’s Bank of China about the risks of excessive decline in long-term interest rates, these measures helped alleviate the “big banks lend, small banks buy bonds” cycle. As a result, there was a slowdown in loan growth in large banks compared to small banks, along with a noticeable deceleration in the bond purchase growth at small banks. However, surprisingly, after this crackdown, M1 growth turned negative in May 2024.

In my September 2024 article, “Revisiting the ‘Scissors Gap’ Between M1 and M2: Efficient Credit Expansion Requires Three Key Approaches,” I discussed how pro-cyclical fiscal tightening played a critical role in the fall of M1. The decline in fiscal revenues from land sales, coupled with rising debt repayment pressures, significantly reduced the fiscal resources available to support the real economy. This, in turn, led to negative M1 growth through what is known as the “fiscal accelerator effect.”

Following the policy shift on September 24, 2024, fiscal spending increased in the fourth quarter of 2024, leading to a gradual stabilisation of second-hand housing prices and a rise in financial market activity, both of which helped to enhance the use of deposit. As a result, the “scissors gap” between M1 and M2 began to narrow sharply from October 2024, and the imbalance between demand and time deposits was significantly alleviated.

The second structural change is the disproportionately large amount of household deposits relative to corporate deposits.

Since the pandemic, household deposits in China have accumulated at an accelerating rate compared to corporate deposits. Household deposits rose from 94 trillion yuan in January 2021 to 157 trillion yuan in February 2025, an increase of nearly 67%. In contrast, corporate deposits grew from 67 trillion yuan to 77 trillion yuan during the same period, a more modest increase of just 15%. Corporate deposits even experienced a year-on-year decline in April 2024, a phenomenon that had never occurred before.

How can this phenomenon be explained? First, in a low-inflation environment, household consumption remains subdued while corporate profit margins have been squeezed. As a result, some businesses, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, have ceased operations, leading to a shift in deposits from the corporate sector to the household sector. According to the latest data from the State Administration for Market Regulation, the number of active market entities in China saw a rare decline in the first three quarters of 2024, with a rebound in the fourth quarter. In the first 11 months of 2024, only 5 million new market entities were established, compared to approximately 15 million per year between 2020 and 2023, indicating a significant slowdown.

Secondly, the decline in corporate demand deposits in April 2024 can also be attributed to the crackdown on banks’ improper use of manual interest rate adjustments. Previously, some bank employees bypassed internal pricing authorisations, using manual interest rate adjustments to attract deposits with high interest rates, particularly from corporate demand deposits. Following the release of the “Proposal to Prohibit the Use of Manual Interest Rate Adjustments to Attract High-Interest Deposits and to Maintain Fair Competition in the Deposit Market” on April 8, 2024, a large portion of corporate demand deposits was converted into time deposits or transferred to off-balance-sheet wealth management products. With the crackdown on manual interest correction practice, the cost of corporate demand deposits for large banks was effectively reduced.

The two factors above explain the reduction in corporate deposits. However, data-wise, it is clear that the increase in household deposits since the pandemic far exceeds the decrease in corporate deposits, a trend that cannot be fully explained by “the reduction in the number of market entities.” The crackdown on manual interest rate adjustments, which only took effect in April 2024, also cannot account for this long-term change. Therefore, the third and most important reason is the blockage in the internal circulation of money from household deposits to corporate deposits.

Where did the 157 trillion yuan in household deposits originate?

Since loans create deposits, a reduction in household consumption or investment does not alter the total volume of deposits but rather affects their distribution between the household and corporate sectors. Based on the household flow of funds equation, household funds derive from income and borrowing, and are allocated toward consumption, home purchases, and financial investments. The unspent portion is retained as deposits, represented by the following equation:

As the household sector deleverages, the rapid growth in household deposits can be attributed to several factors: increased earnings (through wage income), higher savings (resulting from reduced consumption and property purchases), and adjustments in financial asset allocation (through a reduction of financial asset investments, transferring from off-balance-sheet to on-balance-sheet assets).

Data indicate that, since 2022, China’s per capita disposable income has continued to rise, while consumption and investment demand have remained subdued. Prior to the policy shift at the end of September 2024, the capital market had experienced three consecutive years of decline, further weakening households’ appetite for financial investments. The combined effect of these three factors has driven the sustained increase in household deposits.

What are the implications of excessive household deposits?

Some may argue that the rise in household savings is a positive development, suggesting that households have more money. In the short term, households indeed have more financial resources at their disposal as a result of reduced consumption, home purchases, and financial investments. However, from an economic circulation perspective, the disproportionate increase in household deposits relative to corporate deposits reflects an inefficient internal circulation of funds between the corporate and household sectors. This imbalance may undermine the efficiency of future monetary expansion and constrain economic growth.

The flow of money between the corporate and household sectors primarily occurs through two channels: first, businesses pay wages to households, converting corporate deposits into household deposits; second, households engage in consumption and investment, transferring household deposits back into corporate deposits.

Although wage payments from businesses have remained stable, maintaining a steady flow from the corporate sector to households, the sharp decline in household consumption and investment has disrupted the flow of deposits to the corporate sector.

A key factor contributing to this disruption is the weakened demand for housing. Historically, the real estate market has served as a critical channel for transferring household deposits into corporate deposits. During periods of real estate expansion, household deposits were rapidly converted into pre-sale payments for real estate companies, thereby boosting corporate demand deposits. However, amid a major adjustment in China’s real estate cycle, the total sales area of commercial housing has fallen sharply, from a peak of 1.8 billion square meters in 2021 to less than 1 billion square meters in 2024. This decline has significantly weakened the mechanism through which household deposits flow into corporate deposits via real estate transactions, thereby slowing the growth of corporate deposits.

As household deposits become increasingly trapped within the household sector, businesses face a shortage of incremental funding for investment, undermining their operational capacity. Consequently, the accumulation of funds within households slows the overall velocity of money. Data indicate that the gap between the growth rates of corporate and household deposits serves as a leading indicator of money circulation velocity: when the growth rate of corporate deposits lags behind that of household deposits, it typically slows down money velocity and reduces the effectiveness of monetary expansion.

In addition to the imbalance between demand and time deposits, and between corporate and household deposits, a third structural change in M2 is the rapid increase in deposits from non-bank financial institutions, while the growth of deposits from the real economy remains relatively sluggish.

Deposits from non-bank financial institutions refer to interbank deposits from entities such as securities firms, mutual funds, insurance companies, wealth management subsidiaries of commercial banks, finance companies, and insurance asset management firms. As of February 2025, deposits from non-bank financial institutions had exceeded 30 trillion yuan, accounting for approximately 10% of M2. These deposits are typically shorter in duration and more volatile. By contrast, deposits from households and businesses are more diversified and stable, enabling banks to expand credit more effectively and improve regulatory indicators.

Historically, state-owned commercial banks, with their large deposit bases, served as direct counterparties to the central bank in open market operations, allowing them to access liquidity with great ease. With abundant low-cost funding, they typically acted as lenders in the financial market. In contrast, non-bank financial institutions were primarily borrowers of funds and served as “price takers” in the money market.

However, in 2024, the year-on-year growth rate of funds borrowed by non-bank entities from banks turned negative, signalling a reversal in the traditional flow of funds—now from non-banks into banks. This structural shift is reflected in M2: deposits from non-bank financial institutions began to accelerate both in scale and in growth rate from September 2023, with the trend becoming particularly pronounced in the third quarter of 2024.

Why has there been a surge in non-bank deposits? There are two main reasons:

First, from the perspective of depositors (businesses and households), following the crackdown on manual interest rate adjustments and the reduction of deposit rates in April 2024, the appeal of traditional bank deposits has diminished significantly in a low-interest-rate environment. The average one-year time deposit rate at banks has fallen to just 1.6%, lower than the returns offered by bond-investing funds, wealth management products, and even money market funds.

As the saying goes, “Water flows to lower places, and money flows to where returns are higher.” In search of better yields, households and businesses have increasingly moved funds out of the traditional banking system and into money market funds, bond funds, and wealth management products. This trend has resulted in "bank disintermediation."

From the banks’ perspective, there is also a strong incentive to absorb non-bank deposits. Following the elimination of manual interest adjustments and several rounds of deposit rate cuts, many businesses shifted their funds into wealth management products and bond-investment funds. Confronted with a shortfall in deposits, banks were compelled to raise interbank deposit rates to attract deposits from non-bank financial institutions, thereby easing pressure on their liability side.

If the expansion of non-bank deposits is not effectively controlled, it could lead to instability of banks’ sources of funds, higher liability costs, and an increase in overall financial risk. Non-bank deposits, by nature, are typically short-term and closely tied to movements in financial markets. As the share of non-bank deposits in banks’ liabilities rises, it could erode the resilience of the financial system.

A notable example is the U.S. repo market crisis in September 2019. In the United States, money market funds play a critical role in the repo market by providing short-term financing to banks, thus maintaining liquidity in the financial system. However, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet unwinding, which began in 2017, shrank bank reserves from $2.3 trillion to $1.4 trillion by September 2019, approaching historically low levels. Combined with seasonal factors such as corporate tax payments and government bond auctions on September 16, banks’ demand for short-term funds surged sharply. At the same time, money market funds—major lenders in the repo market—faced concentrated redemption pressures during the tax period and became reluctant to lend. As a result, banks suffered rapid deposit outflows, reserve depletion, and were unable to secure sufficient financing from the repo market. This triggered a sharp tightening of money market liquidity, with the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) spiking by 282 basis points to 5.25%, exceeding the upper bound of the Federal Reserve’s target range.

In the context of China, after depositors shift funds into wealth management products, a portion of these funds effectively flows back into the banking system as non-bank deposits, but through institutional channels. Since non-bank institutions typically control larger pools of capital and possess greater bargaining power, banks face higher funding costs when borrowing from them. For example, in early November 2024, some major banks offered non-bank interbank demand deposit rates as high as 1.8%, significantly exceeding the central bank’s 7-day reverse repo rate.

Thus, the excessive expansion of non-bank deposits will drive up banks’ liability costs and compress their net interest margins. Reflecting this pressure, the net interest margin of Chinese commercial banks continued to decline throughout 2024, reaching a historic low of 1.52% by year-end.

However, restricting the expansion of non-bank deposits may introduce new challenges to bank liquidity. In an effort to alleviate pressure on banks’ net interest margins, the work conference on the self-regulatory mechanism of interest rate pricing (中国人民银行市场利率定价自律机制工作会议) organised by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) in November 2024, approved two initiatives: the Proposal to Optimise the Self-Regulation of Non-Bank Interbank Deposit Rates and the Proposal to Introduce “Interest Rate Adjustment Clauses” in Deposit Service Agreements.

These initiatives require banks to use either the PBOC’s 7-day reverse repo rate from open market operations or the excess reserve rate as the benchmark for pricing interbank demand deposit rates, thereby ensuring that these rates fluctuate around the central bank’s policy rate. Following the announcement, non-bank demand deposit rates declined, reducing banks’ funding costs from non-bank institutions and potentially mitigating the compression of their net interest margins.

Nevertheless, the new self-regulation rules for non-bank deposits have prompted money market funds to reduce their allocation to deposit-like assets, leading to a contraction in the scale of non-bank financing available to banks. This development has exacerbated liquidity pressures for banks. Since the growth rate of bank assets serves as a leading indicator of broader economic activity, and given that banks’ excess reserve ratios have already declined to historic lows, a continued slowdown in the expansion of bank balance sheets could place additional strain on the ongoing recovery of the real economy.

3. Policy Recommendations

To date, one of the three new structural changes in M2—the imbalance between demand and time deposits—has been partially alleviated. However, the imbalances between corporate and household deposits, as well as between deposits from non-bank financial institutions and those from the real economy, persist. This suggests that the core challenge facing current monetary policy is the difficulty in effectively translating funding liquidity into market liquidity.

At the root of this issue, against the backdrop of low expected returns in the real economy (or low risk appetite), funds within the financial system naturally display a “search for yield” behaviour.

The PBOC has sought to curb the idle circulation of funds and redirect liquidity from the financial system into the real economy. First, in 2024, it targeted the practice of manual interest rate adjustments and lowered deposit rates, effectively restraining the phenomenon of enterprises “borrowing at low interest rates while depositing at high interest rates,” a behaviour that had contributed to the accumulation of idle funds.

However, rather than flowing into the real economy, money has continued to pursue higher returns within the financial system. Capital has gravitated toward the highest-yielding assets, initially moving into bond-investing funds and subsequently shifting toward wealth management products and money market funds as bond prices declined. In the context of weak aggregate demand, relying solely on monetary policy adjustments creates a paradox: as the PBOC lowers household and corporate deposit rates, interbank deposit rates rise, resulting in money merely circulating within the financial system without reaching the real economy.

Such inefficiencies may even push monetary policy into a dilemma. To stimulate economic activity, the monetary supply must remain flexible. However, if liquidity is merely recycled within the financial system—for instance, leveraged to purchase government bonds or placed in interbank deposits—concerns over financial stability could intensify. In such cases, tightening monetary policy to enforce monetary discipline could inadvertently exacerbate liquidity shortages within the banking sector.

The key to resolving this dilemma lies in addressing the blockage in the transmission of monetary policy. At present, the bottleneck lies in insufficient household consumption and investment, which has disrupted the internal circulation of funds between the household and corporate sectors. This imbalance is evident in the composition of M2, where the proportion of household deposits continues to increase, while the growth rate of corporate deposits has slowed markedly or even turned negative.

How can this blockage be cleared?

First, preserve money supply elasticity at the macro level to alleviate liquidity pressures arising from deposit outflows. In 2024, the PBOC implemented a series of measures, including the crackdown on manual interest adjustments, the reduction of deposit rates, and the regulation of non-bank interbank deposits. These initiatives significantly curbed idle funds and strengthened monetary policy discipline.

However, as deposit rates declined, the resulting outflows of corporate and household deposits placed additional pressure on bank liquidity. Since the beginning of 2025, interbank liquidity conditions have tightened, as evidenced by the rising 7-day weighted average interest rate for pledged repo transactions across the entire market (R007), the 7-day weighted average interest rate for pledged repo transactions among deposit-taking institutions (DR007), and interbank certificates of deposit rates. Given that China’s financing structure has traditionally been dominated by indirect financing, with monetary policy transmission heavily reliant on the bank lending channel, sustained liquidity stress within the banking sector could intensify pressure for balance sheet contraction and transmit tightening effects to the broader credit market.

Thus, it is critical to strike an appropriate balance between maintaining monetary policy discipline and preserving money supply elasticity, thereby safeguarding liquidity stability within the banking system.

Second, guide the structural allocation of money. To address the bottleneck caused by insufficient household consumption, structural monetary policies should be implemented through a combination of innovative instruments and targeted interest rate reductions. These measures can direct financial institutions to better meet the diverse financing needs of different sectors, thereby creating a more supportive financial environment to stimulate household spending.

Measures could include developing consumption-oriented structural monetary policy tools that support financial institutions in extending consumer credit and provide low-cost funding to key sectors such as culture, tourism, elderly care, and sports. Additionally, consideration should be given to reducing the interest rates on structural monetary policy tools to lower their cost of use. As of December 2024, most existing structural monetary policy tools maintained an interest rate of 1.75%, while the 7-day reverse repo rate had been reduced to 1.5%. A moderate reduction in the re-lending rate could incentivise banks to make greater use of these structural tools to support consumption, thereby improving the efficiency of monetary policy transmission.

Third, strengthen the coordination between fiscal and monetary policies to enhance both the ability and willingness of households to consume. If households are not spending, an abundant money supply combined with structural imbalances will result in funds becoming trapped within the household sector, thereby impeding efficient credit expansion. Consequently, coordination between fiscal and monetary policies is needed to optimise deposit allocation and improve the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission.

Fiscal policy can focus on two key areas. First, increase household income to strengthen consumption capacity. Direct measures to boost income could include providing tax reductions and rebates for low-income groups and raising the personal income tax threshold. Given that rural residents generally have a higher marginal propensity to consume than their urban counterparts, enhanced subsidies and support for low-income rural populations could yield a significant positive impact on consumption. Moreover, increasing public investment in areas such as new energy, digital infrastructure, and underground utility networks would help create employment opportunities, thereby supporting income growth through job creation and wages.

Second, fiscal policy should aim to enhance households’ willingness to consume. By employing fiscal tools such as consumption subsidies and interest rate subsidies, governments can promote consumption while addressing structural weaknesses in key industries and improving public welfare. Strengthening fiscal support for sectors such as childbirth services, elderly care, and education across multiple dimensions would help reduce households’ precautionary savings.

An especially important step at present is to innovate fiscal-monetary coordination mechanisms. For example, new models could be explored involving property and land acquisition by state-backed developers, alongside capital injections into the real estate sector. Special purpose entities could be established, with the MOF providing capital contributions or interest subsidies to absorb credit risk, while the PBOC offers re-lending support. This approach would help stabilise real estate prices, improve household balance sheets, bolster long-term income expectations, and ultimately raise the marginal propensity to consume.