Li Xunlei warns against excessive industrial investment amid declining demand and population

Economist urges Beijing to shift focus to service sector investment, emphasizing that productivity gains in the industrial sector fail to create employment opportunities.

Li Xunlei is Chief Economist at Zhongtai Financial International Limited and has worked extensively at other Chinese securities companies, including Junan Securities, Guotai Junan Securities, and Haitong Securities. He is one of the most renowned chief economists among major domestic securities firms in China.

The article was originally published on 李迅雷金融与投资 Finance & Investment with Li Xunlei, Li's personal WeChat blog. The East is Read has translated the latter part of the article which focuses on a more concrete discussion of the problems in the Chinese economy.

Li Xunlei attributes China's economic challenges primarily to its population decline, warning of its ripple effects on insufficient consumption demand, a shrinking real estate sector, and worsening economic stagnation. While sharing a similar foundation to James Jianzhang Liang—whose speech The East is Read published last Saturday—Li focuses his arguments on how fiscal spending should address the core issues of the Chinese economy—the "bullseye," he called it.

Li critiques China's overreliance on investment-driven growth and infrastructure expansion, noting that a focus on the industrial sector has exacerbated overcapacity and employment pressures, as productivity growth in manufacturing does not translate into employment opportunities. To counter this, Li advocates for increased fiscal investment in the service sector, including healthcare, education, and eldercare, as a means to boost consumption and absorb surplus labor from manufacturing as productivity improves. This shift, he emphasizes, is essential for addressing employment challenges, particularly the disproportionately high unemployment rate among urban youth.

—Yuxuan Jia

李迅雷:射中经济问题的靶心难吗?

Li Xunlei: Is It Difficult to Hit the Bullseye of Economic Issues?

Lessons from the Past: Pay Close Attention to the "Aftermath" of Economic Contraction

Since the burst of its real estate bubble in the 1990s, Japan's economy has fallen into a prolonged period of deflation. At the end of 1991, Japan's Consumer Price Index (CPI) stood at 93.1, and it only reached 100.1 by the end of 2021—a cumulative increase of just 7.5% over 30 years. Although Japan's CPI experienced brief upticks during the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis, it hovered around zero throughout the 30 years following the bubble collapse.

On the other hand, Japan's per capita GDP reached $40,000 in 1994. By 2023, when calculated at constant prices of 1994, it had dropped to $25,000, which is partly attributable to the depreciation of the yen. In contrast, the United States had a per capita GDP of $28,000 in 1994. By 2023, calculated at 1994 constant prices, its per capita GDP had risen to $56,000, doubling the 1994 level.

In November of last year, I wrote an article titled "How to Address the Multiplier Effect of Economic Contraction?" in which I explained that although China's current GDP growth remains around 5%, with household income growth largely in sync with GDP, it is essential to plan ahead. For example, it is anticipated that China's budget revenue will experience negative growth in 2024, and the total profits of listed companies may decline for two consecutive years since 2023 (according to data from the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, total profits of state-owned enterprises fell by 2.1% from January to August 2024).

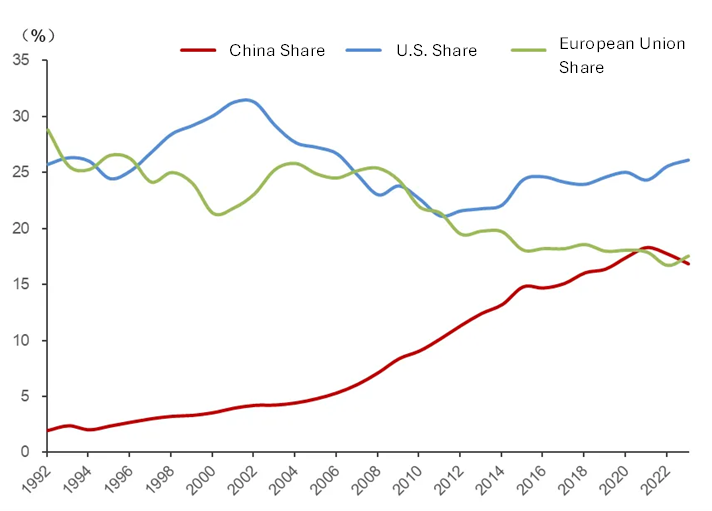

The necessity of closely monitoring—and even fearing—the multiplier effect of economic contraction arises from the same logic as the multiplier effect during periods of economic expansion. For instance, between 1992 and 2022, China's share of global GDP surged from 2% to 18%, an achievement nothing short of miraculous. This was largely the result of a synergistic effect driven by the demographic dividend, reform dividend, and the accelerated development of industrialization and urbanization.

However, China's total population has been declining for two consecutive years, with the proportion of the elderly population reaching 15.4%. By 2031, it is estimated that China will enter a "super-aged society." Additionally, real estate investment and sales have been on the decline for three years.

China's current long-term downward cycle in real estate bears some resemblance to the backdrop of Japan's real estate bubble collapse, that is, accelerating aging. Japan became an "aged society" in 1994, while China reached this stage in 2021. Additionally, China's population peaked in 2021, the same year as the real estate market topped out. In Japan, however, the population peak occurred in 2010, 19 years after the real estate bubble burst.

Some may argue that China's urbanization rate, currently at 65%, still offers room for a 15% increase and that real estate may not enter a long-term downward cycle. While this is a valid point, future urbanization may not necessarily be driven by rural-to-urban migration. Instead, it could result from a shrinking denominator (total population). In this case, the process would not significantly increase demand for real estate, especially as demand in third-, fourth-, and fifth-tier cities is likely to decline over time.

In the first three quarters of 2024, revenue from use rights sales of state-owned land dropped by 24.6% compared to the same period in 2023 and by 56.6% compared to the same period in 2021. This decline is striking and appears to be accelerating. The sharp decrease in land sale revenues indicates a significant contraction in demand, which negatively impacts the entire upstream and downstream real estate supply chain. This is an example of the so-called multiplier effect, or the "aftershock," which begs for heightened attention.

Can Fiscal Spending Hit the Right Target?

To compensate for the decline in investment caused by the collapse of its real estate bubble, Japan significantly expanded its public investment. For example, from 1995 to 2007, Japan allocated a staggering ¥650 trillion from its budget to infrastructure construction, four to six times higher than the U.S. spending during the same period. By 1998, workers in public construction accounted for 10% of Japan's total labor force, reaching 6.9 million people. Japan, as an island nation with nearly 6,800 islands of various sizes, used this investment to connect almost all major islands with bridges and highways. Much of its extensive coastline has been covered in concrete. However, after 2010, Japan's population began to decline, and over 90% of its islands are now uninhabited. According to a United Nations Population Division report, Japan's population will decrease to approximately 75 million by 2100, leaving much of its infrastructure abandoned.

22 years ago, Alex Kerr, an American scholar based in Japan, published a sensational book titled Dogs and Demons. The seemingly peculiar title originates from a well-known Chinese anecdote found in Han Feizi, Outer Stored Sayings (Part One):

In the ancient Chinese philosophical treatise Han Feizi, the emperor asked a painter, "What are the hardest and easiest things to depict?" The artist replied, "Dogs and horses are difficult, demons and goblins are easy." By that he meant that simple, unobtrusive things in our immediate environment like dogs and horses are hard to get right, while anyone can draw an eye-catching monster.

—Kerr, Alex. Dogs and Demons. Penguin Books, 2001, pp. 145–146.

Kerr used this anecdote to highlight Japan's challenges—finding effective solutions to real problems is exceedingly difficult, yet pouring massive funds into lavish projects is all too easy. Clearly, Japan at the time failed to take strong measures to address its persistent deflation problem or implement bold efforts to stimulate consumption. Instead, it became an "infrastructure construction maniac," a strategy that was fundamentally counterproductive.

This serves as a cautionary tale. Increasing fiscal spending and investing heavily in infrastructure does not guarantee a remedy for all economic problems. It's akin to how, in 1935, an Italian engineer attempted to stabilize the Leaning Tower of Pisa by injecting 80 tons of mortar into its foundation, only to worsen the tilt. Similarly, China's 3.3% growth in total retail sales of consumer goods for January-September 2023 and the 0.4% CPI growth in September confirm the Central Economic Work Conference's diagnosis of one of the year's key challenges: "lack of effective demand."

The "lack of effective demand" should not be understood as the lack of effective investment demand because investment demand is not final demand. Instead, it should be interpreted as the "lack of effective consumption demand." This aligns with the Central Economic Work Conference's identification of "overcapacity in some sectors" as the second major challenge.

It is apparent that many people do not fully grasp the logic of expanding domestic demand. While domestic demand includes both consumption and investment demand, investment ultimately results in "capital formation," which increases total supply in the economy. If the supply of goods and services continues to grow without a corresponding increase in consumption demand, the imbalance between supply and demand will worsen, leading to further declines in the prices of goods and services.

China accounts for 31% of the world total of manufacturing value-added with only 17.6% of the global population, underscoring its substantial reliance on exports. Moreover, there has been relatively little attention paid to the issue of "excess transportation capacity." For instance, as of 2023, China's high-speed rail network accounts for 70% of global total mileage; China's expressways span 177,000 kilometers, ranking first globally and comprising about 40% of the world's total; China's metro systems make up 48.6% of global mileage.

In addition, as of May 2024, China had built 3.84 million 5G base stations, accounting for 60% of the global total, despite urbanization levels far below developed countries. This suggests that in many sectors, China's production capacity or transportation capabilities have already outpaced its population's proportion in the global demographic.

Moreover, the maintenance costs of infrastructure are extremely high. In the context of a declining total population and reduced population mobility, long-term planning and prudent investment are even more critical. According to estimates, the median return on invested capital (ROIC) for China's infrastructure projects has dropped from 3.1% in 2010 to 0.46% in 2023. Whether drawing lessons from Japan's post-1990s experience or analyzing China's current economic conditions, the conclusion is clear: the top priority should be to improve people's livelihoods and stimulate consumption to avoid a prolonged situation where the CPI hovers near zero.

How to Hit the Bullseye of Current Economic Challenges: Does Stabilizing Growth Automatically Stabilize Employment?

A widely accepted notion is that GDP must maintain a certain growth rate; otherwise, employment issues will arise—hence the idea that "only by stabilizing growth can employment be stabilized." However, let's consider an extreme example: suppose 70% of a country's fiscal expenditure is allocated to equipment upgrades and AI research and development, while the remaining 30% is used for day-to-day expenses. The result is that, after several years, productivity in the country's industrial sector increases significantly, while the number of workers employed in the sector decreases substantially. Meanwhile, other sectors, lacking sufficient investment, would be unable to create new employment opportunities. As a result, total employment in society would decline, even though GDP growth, driven by investment, would not experience a downturn. Therefore, stable growth may not necessarily increase employment.

In fact, due to an aging population and the continued decline in birth rate, China's working-age population has been decreasing since 2012, and the total employed population has been declining since 2018, with a reduction of 36 million by 2023. This indicates that as productivity improves, the employed population in a company can generate more GDP. Furthermore, since productivity varies across different industrial sectors, the same scale of capital investment creates different levels of employment in different sectors.

For example, after 2013, the total number of employed individuals in the secondary sector began to decline, and its share of the total national employed population also decreased. In 2023, employment in China's secondary sector had decreased by 17.06 million compared to 2012. With the growth rate of manufacturing investment still reaching 9.2% from January to September this year, the trend of declining employment in manufacturing is likely to continue.

Western countries, after entering the post-industrial era, have typically focused on developing the service sector, as it can absorb a larger portion of the workforce. Currently, 84% of the U.S. workforce is employed in the service sector, while the share in Germany and Japan is around 70%. Even Germany and Japan, known for their craftsmanship and industrial strength, have such high proportions of service employment. In comparison, only about 50% of China's total employed population works in the service sector. Should China also consider increasing investment in the service industry?

This does not conflict with the goal of becoming a manufacturing powerhouse, as being a manufacturing leader is a quality metric. With rising productivity in manufacturing, surplus workers can naturally transition to the service sector. The key lies in significantly increasing fiscal investment in the service sector. Enhancing people' incomes and boosting spending on education, healthcare, and elderly care—key components of social security—would provide the strongest support for developing the service sector.

Looking at actual spending data, since 2021, despite a sharp slowdown in real estate investment growth, manufacturing investment has increased substantially. This has allowed China's investment-to-GDP ratio to remain at twice the global average.

Investment is a fast-moving variable that can quickly translate into GDP as long as physical progress is made. In contrast, economic transformation is a slow-moving variable, shaped by numerous uncontrollable factors such as systemic and institutional barriers. However, the tangible reality of annual GDP growth targets forces a choice of priorities. As humanity enters the AI era, rising productivity will inevitably heighten employment pressures. According to data released by the National Bureau of Statistics, in September, the unemployment rate among urban youth aged 16–24 (excluding students) reached 17.6%, significantly higher than in previous years, despite overall, the urban surveyed unemployment rate being 5.1%. This highlights the need to create more job opportunities for young people.

To address this, full employment should be prioritized among the many macroeconomic indicators, and relevant industrial policies should revolve around this objective. If the final consumption-to-GDP ratio can be raised to over 60%, the urban surveyed unemployment rate will definitely decline again, CPI will rise, and the economy's transformation will begin to show promise. In fact, the National People's Congress has long set new job creation as a binding target—one that must be achieved—while GDP growth has always been an expected goal that does not necessarily have to be met.

In summary, solving economic challenges is far more complex than stabilizing the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The latter is a purely technical problem in the natural sciences, whereas the former involves a web of constraints and competing interests rooted in the humanities.