Lan Xiaohuan on government industry guidance funds in China

The Chinese bestseller on the interplay between Chinese govt and market is now available in English.

The East is Read is privileged to publish an excerpt from How China Works: An Introduction to China’s State-led Economic Development by 兰小欢 Lan Xiaohuan, Professor, School of Economics, Fudan University. Prof. Lan is also a research fellow at the Shanghai Institute of International Finance and Economics and holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Virginia.

The original Chinese version, 置身事内:中国政府与经济发展, was a 2021 bestseller in China. Pekingnology, a sister newsletter of The East is Read, was graciously authorized by Prof. Lan to translate and publish an excerpt of the book when it was only available in Chinese.

Now with the publication of the official translation, translated by Gary Topp and published by Palgrave Macmillan, The East is Read is pleased to present this excerpt to its readers. We also invite you to click on the link to order a copy of the book or access it at Springer via your institution free of charge.

The following excerpt discusses the development and operation of government industry guidance funds in China. It explains how these funds differ from traditional venture capital systems, highlighting their adaptation to the Chinese political and economic context

CHAPTER 4. Section 3: Government Industry Guidance Funds

Industrial upgrading and technological innovation have become hot topics in China during recent years. When it comes to funding for high- tech companies, Silicon Valley style venture capital investment is often the first thing that comes to mind. However, an American style venture capital system cannot be directly replicated in China. Instead, venture capital investment was adapted to the Chinese political and economic context and mixed with funds from local government, creating “government industry guidance funds”. This new tool of equity investment in high-tech sectors was born out of the traditional model of local government invest- ment and financing. But the old model is associated with a huge debt problem and cannot continue growing fast. With reforms increasingly focused on reducing excessive debt and reducing industrial overcapacity, these new “government guidance funds” more than doubled in size from 2014 to 2019. According to data from Zero2IPO, as of June 2019, there were 1,686 “industry guidance funds” already established in China, with total funding of 4 trillion yuan in place, and according to separate data from ChinaVenture, there were 1,311 funds with total funding of 2 trillion yuan.

Government industry guidance funds not only provide a new tool to attract investment and to drive industrial policy, they also represent a more market-orientated way of using government money. Understanding such funds could help us understand the industrial development in China. At the same time, it is also an excellent example of “China’s gradualism in economic reform”. Government guidance funds are closely related to private equity funds, and therefore we must first understand how private equity funds work.

Private Equity Funds and Industry Guidance Funds

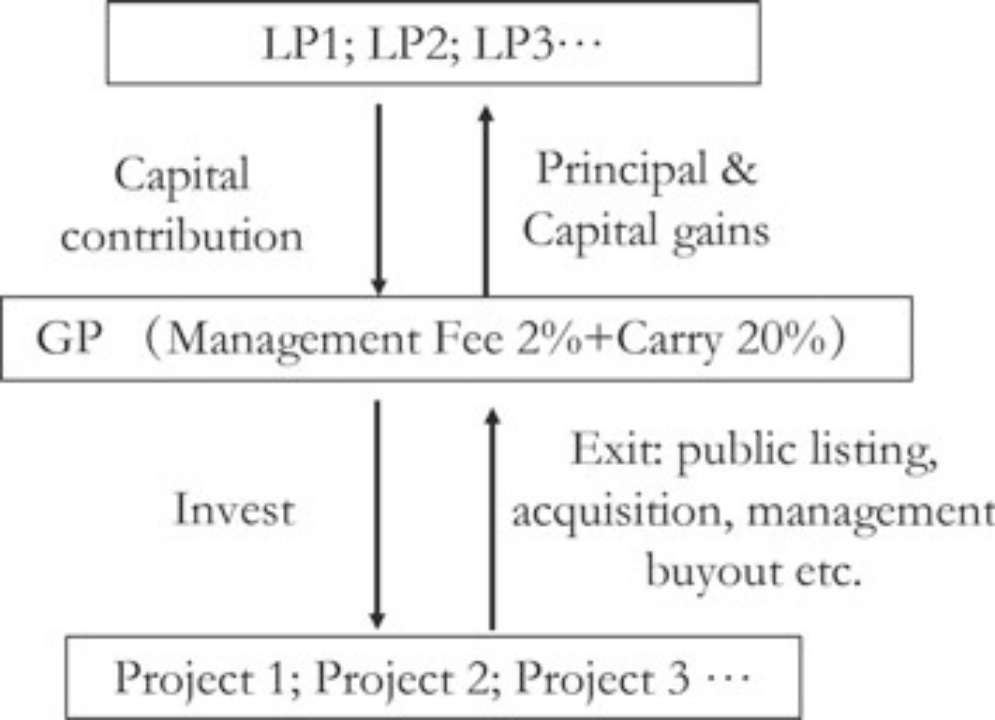

Put it in the simplest terms, private equity funds (PE) involve a group of people who give money to another group of people to carry out and manage investments. The two groups then share in any returns from the investments. It is called private in order to distinguish it from mutual funds that are available for anyone to buy on the public market. PEs have special regulations governing investor qualifications, fundraising and exit methods, and they are not like the shares of mutual funds which can be bought and sold on a daily base. Figure 4.1 depicts the basic operational structure of PE. The person who contributes the money is known as a limited partner (LP), and the person who manages the money and investments is called a general partner (GP). The LP hands money to the GP in order to carry out investments, and pays fees to the GP in return for their services. Typically, these fees include a management fee, typically 2% of the LP’s contributed money. This fixed fee should be paid regardless of the GP’s investment returns, even if the GP loses money. The second type of fee is performance-based, known as “carry”. If the investment makes money, the GP must first repay the principal to the LP along with any pre-agreed baseline return (typically 8%). If there is any profit above this baseline return, then the GP can earn commission of around 20% on it.

To give a simple example. A LP invests 1 million and the fund is active for 2 years, then the GP receives 20,000 in management fees every year. If the fund were to lose 500,000 in two years, then the GP would earn a total of 40,000 in management fees and the LP would receive only 460,000 back, recognizing a loss. If the fund were to earn 500,000 over 2 years, then the GP would still earn 40,000 in management fees. Given the return is now positive, the GP would return to the LP 1 million in principal plus the pre-agreed baseline return of 8% per year or 160,000. For the remaining extra profits of 300,000, the GP would take 20% “carry” or 60,000, and return 240,000 to the LP. In total the GP earns 100,000 for his service and the LP gets back 1.4 million in principal and profits.

GPs could invest in publicly listed companies or in the equity of unlisted companies, it may also involve private placements of publicly listed companies. If the investment is an unlisted company, there are many ways to exit, for example selling shares after IPO (initial public offering), selling shares back to the company’s management, or alternatively, allowing the company to be acquired.

The legal structure under which LPs and GPs cooperate is known as a limited partnership. Compared with corporations and joint stock companies, a limited partnership is more flexible. Joint stock companies require an equal number of shares to have an equal number of votes and to have an equal claim on profits. Regardless of the number of shares held, the voting rights and dividend rights attached to each share are the same. Therefore, the more shares you hold, the more rights you have. However, in a limited partnership, the LP pay the money but only enjoy quite limited rights, it is the GP who makes the investment and management decisions. Not only that, the GP can share 20% of the profits without making any initial investment into the fund. A further difference involves life of the company. Whereas corporations are supposed to operate into perpetuity, PE funds typically have a fixed duration of 7– 10 years. During this time, the fund needs to pass through 4 stages, fundraising, investment, management and exit. After the duration, the fund should be liquidated and all the money should be distributed.

Under this model, it is natural that the GPs take the spotlight, since they are the ones who invest and manage the money. Many GP institutions and their star partners can become famous with a strong track record. Their investment portfolio not only earns high returns, but may also include some famous and influential companies. These star GPs are highly sought after and can raise large funds, sometimes over 10 billion yuan. In contrast, the LPs who provide the money are much more low key. Most of the world’s largest LPs are institutional investors, such as large pension funds. In the US, many top LPs are pension fund, such as the California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS) and the Pennsylvania Public School Employee’s Retirement System (PSERS). Another type of institutional LPs is sovereign wealth funds, such as Singapore’s Temasek and GIC or Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund. In China, the largest type of LPs are government industry guidance funds, these can include funds from the central government, such as the National Integrated Circuit Investment Fund, as well as funds from local government, such as the Shenzhen Guidance Fund.

Compared with the traditional way that local governments’ industrial investment, government industrial guidance funds have three distinct characteristics. First, most guidance funds do not invest directly in industrial firms, rather they give their money to private equity funds to invest on their behalf. A PE fund typically has multiple LPs, in addition to government guidance funds. Therefore, by investing in PE funds, government guidance funds can leverage investment from other LPs and guide them into targeted industries. For this reason, the funds are named “industry guidance”. Additionally, since government guidance funds invest in other funds, they are also known as “fund of funds” or FoF. Second, by handing government funds to private equity managers, a part of taxpayers’ money is managed by private entrepreneurs and subject to market risks. This process involves many institutional reforms and run into many difficulties in practice (see the analysis below). Third, most guidance funds are invested in “strategic emerging industries”, such as chips and electronic cars. These funds are not allowed to invest in infrastructure and real estate, which differentiates them from another similar financial tool commonly used in infrastructural projects, i.e., public–private partnership or PPP.

In the previous chapter, we introduced urban investment corporations. Local governments cannot borrow directly from banks, therefore urban investment corporations act as financing vehicles. Similarly, governments cannot make direct equity investments in capital markets, therefore it is necessary to set up a company to operate and manage the guidance fund. These fund managing companies fall into 3 broad categories. The first group are wholly state-owned enterprises, such as Beijing Yizhuang State Investment, an investor in BOE. The second group are mixed-ownership companies, such as Shenzhen Capital Group Co. Ltd., which is entrusted to manage the huge Shenzhen Guidance Fund. The largest shareholder of this company is the Shenzhen city government, but it only holds a 28% share. The third category is more like CFLD discussed in the previous chapter. Guidance funds in small cities are small in scale, and local governments have neither the resources nor the expertise to establish special management companies for them, so they simply entrust the funds to private companies, such as Prosperity Investment Group.

The concept of government guidance funds is easy to understand. Outside China, institutional investors have had decades of experience acting as LPs and have established industry associations to share investment and governance experience. But in China, there are three prerequisites for the development of government guidance funds as institutional investors. First, institutional and policy changes need to be made, otherwise local governments won’t dare to invest taxpayers’ money into the risky equity market. Second, capital markets need to be relatively developed, and there should be a large number of sophisticated GPs available to manage the government funds. In addition, capital markets should be large and liquid enough for these investments to find channels to exit. Third, industrialization and economic development needs to reach a certain stage, so that there are sufficient investment opportunities available in the high-tech and high-risk strategic emerging industries. A large number of high-tech firms would not appear until the economy is relatively developed.

Institutional Conditions Supporting the Rise of Guidance Funds

In 2005, the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Finance for the first time confirmed that the central and local governments could set up venture capital funds, in order to support startup companies by providing equity investment or by offering financing guarantees. In 2007, the newly revised Partnership Enterprise Law came into effect, and the LP/GP operation model explained above was codified in Chinese law. The first wave of RMB denominated limited partnership funds were soon established. In 2008, the State Council set the policy framework for the establishment of government guidance funds, specifying that their purpose is to “Leverage up and Amplify the impact of fiscal funds, increase the supply of startup capital, and rectify market failures in the allocation of startup capital”. The new framework clarified that government guidance funds can operate as funds of funds, and that private capital can be used together with government funds in order to increase investment in start-ups. Moreover, guidance funds were required to operate with the principles of “guided by government, operated by market rules, scientific decision making, and risk prevention”, which thereby are accepted as basic principles for the operation of government guidance funds across China.

If government money enters a private company in the form of equity, and one day the company goes public, what will happen to the “state owned shares”. Is it necessary to transfer 10% of the value to a state social security fund as is often required for the IPO of a state-owned enterprise? If such a transfer is required, neither local government nor any other state-owned investor would be willing to invest. Therefore, in order to incentivize the participation of state-owned capital in venture capital financing, the Ministry of Finance and other departments stipulated that qualified state-owned venture capital institutions and state-owned guidance funds may apply for an exemption to transfer state-owned shares during an IPO.

GP fees are also a potential issue. Although a 2% management fee and 20% performance commission are an international convention, should they apply to manage public money, particularly for such a high percentage of commission? In 2011, the Ministry of Finance and the National Development and Reform Commission clarified that revenue and risk should be shared between government funds and private capital. That GPs, as well-being able to charge a management fee of between 1.5% and 2.5%, could also charge 20% commission on extra investment returns. By explicitly outlining the fee structure, the value created by GPs was recognized and they were no longer treated as a simple investment vehicle.

The above policies provided the institutional framework for govern- ment guidance funds, however their explosive development only started around 2014. The spark that led to this sudden growth was a set of reforms in the new version of the Budget Law. Prior to the reforms, local governments often used various special funds from their budgetary revenues to subsidize firms. After the 2014 reform, the State Council strictly limited the budgetary subsidy provided by local governments to firms. Local governments, which had typically used tax rebates or subsidies directly from their annual budget, had to find a new way to spend the money on firms. Since money not spent within 2 years, according to the new Budget Law, might be transferred to the treasury of higher-level government.

By 2015, the basic institutional framework has been set up. And given that local governments needed a new outlet to invest money on firms, industry guidance funds were ready to go. However, for such a new way to invest public money, a more detailed operation guide was needed. Starting from 2015, the Ministry of Finance and the National Development and Reform Commission have issued a series of detailed rules governing the management of guidance funds, providing guidelines for local governments. There are two guidelines which are most important. First, the principle of “benefits and risk sharing” was clarified once again, recognizing the possibility of investment loss for government guidance funds that use public money. Second, it was clarified that although the treasury department of local government provides capital to funds, “(they) usually do not participate in the day to day operations of funds ”. The rules also stipulate the need for local treasury departments “to help build a good environment for government guidance funds to support industrial development” and to encourage these government investment funds to operate by market rules.

After 2015, the guidance funds begun to expand rapidly. According to Zero2IPO, in 2013, government guidance funds had roughly 40 billion yuan under management. The number grow to 212.2 billion yuan in 2014, 337.3 billion yuan in 2015 and to over 1 trillion yuan in 2016, increasing more than 20 times in just three years (2013–2016). Many of the best-known industry guidance funds were established during this period, including the famous National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, also known as the Big Fund. The fund was established by the Ministry of and Information Technology in 2014, and it raised 140 billion yuan just for the first round. Most local government guidance funds were also established during this period.