China never had free healthcare before its market reforms

"Fully state-funded pension and healthcare systems are not successful models," recalls a former official deeply involved in reforming China's medical insurance system.

Although only a tiny fraction of China’s population truly benefited from the so-called “free” medical care system in the planned economy era, the collective memory of that period remains heavily shaped, and often romanticised, by privileged groups and unsophisticated commentators. They continue to portray it as a utopian, universal free healthcare system that, in reality, never existed.

Before China’s urban medical insurance system reform started in the 1990s, employers largely bore the healthcare costs of the urban workforce. Because almost all urban employers at the time were either proper government or state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the state, or to be more exact, Chinese taxpayers, effectively paid for their healthcare. In the meantime, there was no health insurance and extremely scarce medical resources in the countryside, where most Chinese citizens lived.

As market reforms deepened through the 1980s, the healthcare insurance system’s weaknesses became increasingly apparent. State-owned enterprises grappled with mounting financial pressures that made once-generous medical benefits untenable, a problem compounded by the absence of cost controls, fostering rampant overprescription and waste.

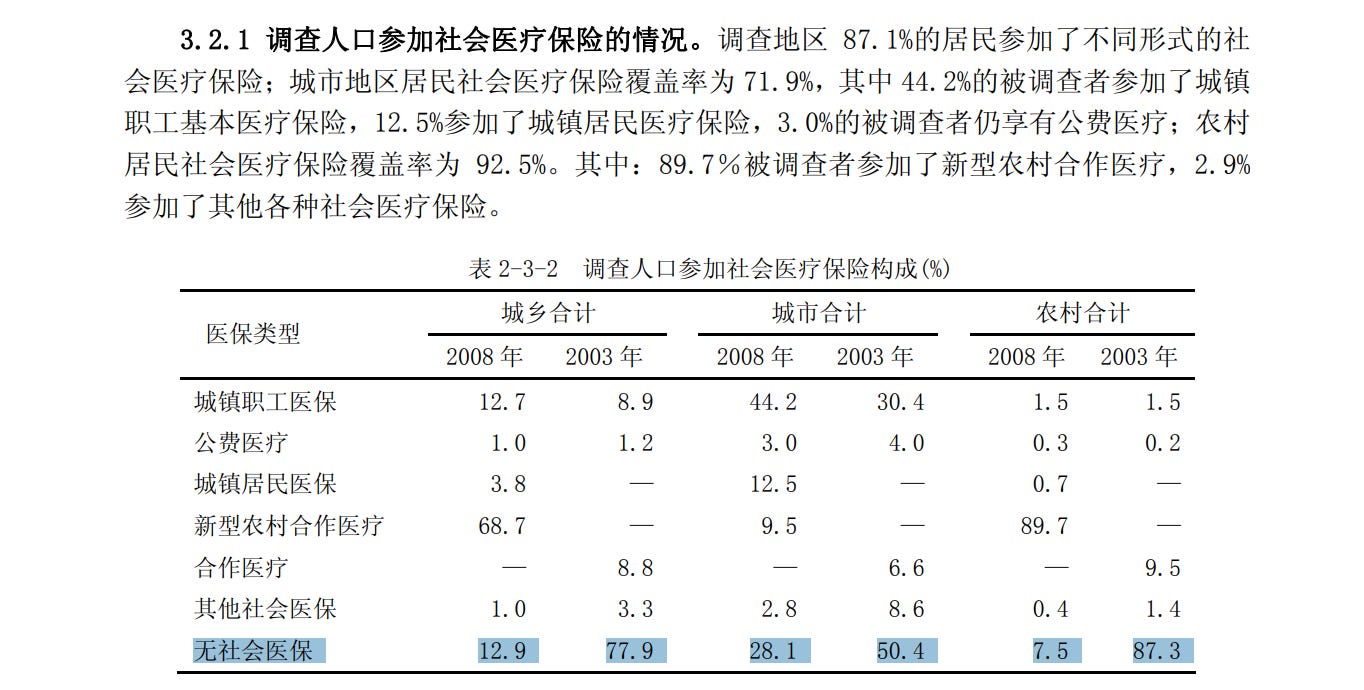

Between 1993 and 2003, three Chinese government surveys consistently showed that 70% of the Chinese urban and rural population did not have any health insurance and had to pay medical costs entirely out of their own pockets.

After reform gathered speed, a 2008 survey, published in October 2009, showed that the percentage of population without health insurance dived from 77.9% in 2003 to 12.9% in 2008.

Recently, Song Xiaowu, a former official who held key posts in China’s economic reform apparatus, offered a retrospective on China’s healthcare insurance reform. Published in China Health Insurance, a magazine overseen by the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA), China’s central medical insurance regulator.

Song reflects on why the old system, often idealised despite its inherent unsustainability, ultimately collapsed. He also charts how, imperfect though it remains, the new insurance system has been painstakingly pieced together over decades.

China’s healthcare insurance reform is an unfinished business. In 2024, 95% of China’s 1.4 billion people were covered under some sort of government-backed medical insurance scheme, significant progress in a middle-income country where GDP per capita is less than 1/6 of the United States. On the other hand, those covered still have to pay substantial amounts of money out-of-pocket, and millions drop out in recent years over rising premiums, forcing the NHSA to come out defending the benefits of the new system last year.

What is often less talked about is that at least some central government ministries still retain, for their employees and retirees, the sort of outdated, unsustainable health insurance benefits on the back of China’s general public. In other words, some of the most powerful government departments continue to enjoy privileges from the old era because the reform hasn’t touched themselves. Their employees receive high-quality medical services at very low personal cost, subsidised by fiscal appropriations from the much less privileged population—subjects of policies crafted in their name. The following article briefly touched upon this point, remembering a senior Chinese leader strongly rejecting any dual-track system that favors government personnel and discriminates against the private sector.

—Zichen Wang & Yuxuan Jia

宋晓梧 Song Xiaowu is the former President of the China Society of Economic Reform under the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Since 1996, he has served as Director-General of the Department of Income Distribution and Social Security at the National Commission for Restructuring the Economic System, Director-General of the Macro System Division at the National Office for Restructuring the Economic System, and President of the Chinese Academy of Macroeconomic Research under the NDRC.

深度访谈 | 中国医保改革的发轫与破冰

In-Depth Interview | The Onset and Breakthroughs of China's Healthcare Reform

From 1996 to 1998, I served as Director-General of the Department of Income Distribution and Social Security under the National Commission for Restructuring the Economic System, while concurrently heading the Office of the State Council Leading Group for the Reform of the Employees’ Medical Insurance System. During this period, I witnessed firsthand the initial stages of China's medical insurance system reform.

From 1998 to 2002, I continued my involvement in healthcare reform as the head of the State Council’s Inter-Ministerial Coordination Group for the Healthcare System Reform.

During this period, I participated in drafting several landmark healthcare reform plans:

The 1998 Employees’ Medical Insurance Reform Plan

The 2000 Urban “Medical Services, Medical Insurance, and Pharmaceuticals” [the healthcare institution management system, the employees' medical insurance system, and the pharmaceutical production and distribution system] Reform Plan

The 2002 New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS)

This period marked both the inception and key breakthroughs in China’s healthcare reform. It saw the establishment of the basic framework for the social security system, including medical insurance, and the launch of reforms in the healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors.

The Two-Jiang Pilot [Zhenjiang City in Jiangsu Province and Jiujiang City in Jiangxi Province] in 1994 and its subsequent nationwide expansion constituted the seminal breakthrough in China's healthcare insurance reform, setting the entire system in motion. Looking back on this pivotal chapter, I am filled with a deep sense of reflection and nostalgia.

Background: Why China Launched Its Healthcare Insurance Reform?

The traditional employee healthcare system, established in the 1950s under the planned economy, primarily consisted of employer-subsidised insurance for enterprise workers and state-funded insurance for government and public institution staff. It represented a historic improvement over pre-1949 China, where access to medical care was extremely limited and medical insurance was virtually nonexistent, and it played a significant role in protecting workers’ health. However, as China transitioned fully to a market economy, the system’s shortcomings became increasingly apparent.

Here are some key data points and cases to illustrate the situation:

The first major issue was the unsustainable rise in medical expenditures, which placed a heavy burden on both state finances and enterprises. Under the traditional system, nearly all healthcare costs were borne by government budgets and employers, with individuals contributing very little. This arrangement eliminated patients’ incentive to save costs. Further compounding the problem was the adoption of the practice of hospitals [Editor’s note: almost all hospitals in China are state-run] funding their operations with profits from overpriced drugs, under which hospitals were allowed to retain a 15% markup on drug sales to offset inadequate government funding—a policy that strongly encouraged overprescription.

According to statistics, employer-subsidised and state-funded medical insurance expenditures in China totalled 2.7 billion yuan in 1978. By 1997, this figure had surged to 77.37 billion yuan—a 28-fold increase, far outpacing the growth of government revenue over the same period. The prolonged and excessive rise in employees' medical costs placed an unsustainable burden on state finances and increasingly strained enterprises and public institutions.

The second major flaw was the lack of cost-control mechanisms for both healthcare providers and patients, resulting in serious waste of medical funds. Under this system, neither group faced effective financial constraints. Employees, largely unaware of medical costs, often sought excessive treatment for minor ailments or unnecessarily opted for high-end services. On the supply side, driven by profit, many medical institutions became vendors of costly medications, imported drugs, luxury nutritional supplements, and even consumer goods such as electric blankets and rice cookers. The Chinese government’s health authorities estimated that roughly 20% of total medical expenditures were wasted. Based on 1997 figures, this translated into an estimated 16 billion yuan in waste—an enormous loss.

The third major issue was the reckless and redundant importation of high-end medical equipment, which led to serious resource misallocation. Some healthcare institutions hastily acquired advanced diagnostic tools such as MRI and CT scanners, resulting not only in substantial waste but also in excessive demand for medical services, including unnecessary and repetitive examinations. Official health statistics showed that China’s positive detection rates for CT and MRI scans were significantly lower than international norms.

The fourth systemic flaw was the absence of sustainable financing mechanisms for medical funds and structured channels for personal contributions, leaving employee healthcare expenses without a stable source of funding. When enterprises experienced financial hardship, many resorted to low fixed stipends (for instance, 3 or 5 yuan per month) or delayed reimbursements, leaving some employees without even basic medical protection. Particularly among struggling firms that had not contributed to the Catastrophic Medical Insurance scheme, unpaid medical reimbursements accumulated to alarming levels. According to investigations, some local medical debts were so large that they could take decades to settle.

I recall a case of an employee at a bicycle factory in Guangzhou who required dialysis for kidney disease. The factory, employing several hundred workers (the exact number escapes me), faced a dilemma: funding his treatment would deplete their entire working capital, meaning that covering one employee’s catastrophic illness could potentially bankrupt the enterprise; yet denying care meant abandoning the worker without medical support. Such difficult choices were not uncommon in that era.

Fifth, healthcare coverage was limited, with insufficient risk pooling in management and services. As foreign-funded and private enterprises rapidly expanded during this period, their employees’ lawful rights to basic medical care went largely unprotected, creating potential social instability.

The lack of effective risk pooling was evident in the continued weakness of state-funded healthcare institutions; moreover, the employer-subsidised system essentially operated as self-insurance by individual enterprises within themselves. Each firm was forced to fully cover its employees’ medical expenses and management costs, resulting in severe imbalances—older enterprises versus newer ones, and disparities across industries—because broader risk-pooling mechanisms across society were lacking.

Against this backdrop, reforming the traditional employer-subsidised and state-funded healthcare insurance systems became imperative. The Two-Jiang Pilot and its subsequent expansion were thus a compelled response to these urgent social challenges. These initiatives had a dual mission: to remedy the shortcomings of the old ssystem and better meet employees’ medical needs, while also supporting economic reforms by helping enterprises overcome financial difficulties. They marked the establishment of a new system, namely, the socialized medical insurance system.

Lessons: The Enduring Legacy of the Two-Jiang Pilot

Against this backdrop, reform of the employees’ healthcare insurance system officially began. In April 1994, with approval from the State Council, the National Commission for Restructuring the Economic System, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Labor, and Ministry of Health jointly issued the “Opinions on the Pilot Reform of the Employees’ Medical Insurance System,” designating Zhenjiang City and Jiujiang City as pilot sites—later known as the Two-Jiang Pilot. This initiative marked a new chapter in China’s employees’ healthcare insurance reform, initiating the crucial “ice-breaking” phase.

After two years of implementation, drawing on lessons from the Two-Jiang Pilot, the State Council issued the “Opinions on Expanding the Pilot Healthcare Insurance Reform,” extending the reforms to over 50 pilot cities.

Through pilot programs, the objectives and principles of healthcare reform were further clarified. I have summarised these fundamentals into ten key points:

Universal basic coverage for all urban workers to establish a comprehensive social safety net.

Align insurance levels with China’s productivity and stakeholders’ capacity, ensuring reasonable cost-sharing among the state, employers, and employees.

Balance equity and efficiency by linking employees’ insurance benefits to their contributions to society, thereby incentivising individual initiative.

Ease the financial burden on employers and public institutions, particularly to support the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) transitioning to modern enterprise models.

Establish financial constraints on both healthcare providers and recipients to promote internal reforms within medical institutions, strengthen management, improve the quality and efficiency of services, reduce waste, and create fair compensation mechanisms for medical institutions.

Implement regional healthcare development planning and gradually socialise clinics operated by SOEs and public institutions to optimise health resource allocation and enhance resource efficiency.

Synchronise reforms of state-funded and employer-subsidised insurance systems by integrating them under a unified reform and policy framework, ensuring that the funding methods and basic structures of the employees’ medical insurance fund remain consistent, while allowing the funds to be managed separately and audited independently.

Separate the roles of government and public institutions, with the government responsible for setting policies and regulations, while relatively independent socialized medical security institutions manage the collection, disbursement, and operation of the employees’ medical insurance fund. Strengthened oversight from multiple stakeholders ensures the reasonable use of funds.

Medical insurance funds operate under budget management principles, where designated funds are used exclusively for their intended purposes, with no misappropriation or embezzlement allowed. Additionally, these funds must not be used to cover fiscal imbalances.

The medical insurance system should be managed by local authorities, with the central and provincial governments (including autonomous regions and centrally administered municipalities), as well as affiliated enterprises and public institutions, required to participate in local insurance schemes under locally uniform contribution standards and locally unified regional reform agenda.

Here are key historical metrics demonstrating the preliminary achievements of China’s healthcare insurance reform during its pilot phase:

First, employees’ basic medical care was secured. The new medical insurance system replaced the previous arrangement, under which individual enterprises and institutions bore full responsibility for medical expenses, leading to unequal healthcare access among employees of different organisations. This reform ensured that employees who previously could not afford treatment due to insufficient funds now received basic medical coverage. For example, in Zhenjiang City, the proportion of employees seeking medical care within two weeks of illness increased from 69.65% in 1994 to 81.70% in 1997, a rise of 12.05 percentage points. Meanwhile, the proportion of individuals foregoing medical care due to financial difficulties declined: among workers, it dropped from 13.1% to 3.9%, and among teachers, from 15.9% to 5.0%.

Second, the rapid growth of medical expenses was curbed. While employees’ basic medical security improved, the growth rate of medical costs slowed compared to pre-reform levels and national averages. For example, in Jiujiang City, per capita medical expenses within government and public institutions increased by 11.6% in 1996 compared to 1994, below the national average annual increase of 20% under the state-funded medical insurance system. In Zhenjiang City, actual medical expenses in 1996 rose by 21.02% from 1994, a slower pace than the 33.4% annual growth recorded between 1990 and 1994. Additionally, the number of high-cost diagnostic procedures and the use of expensive medications both declined.

Third, hospital internal management was strengthened. To ensure a balance between income and expenditure and to promote the rational use of medical funds, medical insurance agencies implemented measures such as fixed-amount settlements and enhanced inspection and oversight of hospital medical costs. These efforts encouraged healthcare providers to improve cost-control awareness, strengthen internal management, and carry out various reforms, thereby enhancing the quality of medical services.

Overall, cities like Zhenjiang and Jiujiang, along with other expanded pilot programs, achieved notable success in exploring the new medical insurance system. The reform’s objectives and principles proved sound. It can be said that the Two-Jiang Pilot, launched under complex socio-economic conditions, successfully fulfilled its assigned reform tasks. In this respect, the Two-Jiang Pilot accomplished its mission.

Certainly, the pilot program also revealed new challenges and deeper systemic contradictions, offering valuable lessons for further advancing the medical insurance reform. For example, as the reforms progressed, issues such as widespread overspending of the social pooling fund and overdrafts in individual accounts emerged, undermining the system’s overall financial stability. These problems were partly linked to hospital-related factors. At the time, health providers’ incomes were directly tied to medicine sales revenue of their hospitals. Doctors not only tolerated practices like “a single account used by multiple individuals” but might even encourage excessive medical consumption. This highlighted fundamental problems within the operational mechanisms of healthcare institutions themselves.

Therefore, it became clear to me that relying solely on reforms of the medical insurance system could not achieve meaningful changes in hospital management or pharmaceutical production and distribution systems. Instead, medical insurance reform must be closely integrated with the management of healthcare institutions and the production and distribution mechanisms of pharmaceuticals, creating a strong synergy. Only through coordinated reforms across these three pillars can the entire healthcare system operate smoothly and develop sustainably.

Addressing this issue, in 1998, Vice Premier Li Lanqing issued a written instruction stating that medical insurance reform alone, without reforms of hospitals and pharmaceutical distribution systems, would never reduce medical costs. In response, the State Council established an inter-ministerial joint conference mechanism, with me appointed as head of the working group at that time.

The “Guiding Opinions on Urban Medical and Health System Reform,” issued in 2000, laid the foundational framework for the coordinated reform of medical services, medical insurance, and pharmaceuticals. Both the concept of the “simultaneous advancement of three reforms” and the subsequent formulation of the “coordinated reform of medical care, medical insurance, and pharmaceuticals” reflected a deep and accurate understanding of the intrinsic links among these sectors, grounded in practical realities.

Tribute: What is the "Two-Jiang Spirit" that We Should Study?

Reform demands both courage and wisdom. The Two-Jiang Pilot and its subsequent expansion were challenging endeavours, marked by complexity and numerous practical difficulties. Yet, leaders from the State Council, heads of relevant ministries, and comrades from the pilot cities worked together in unity, overcoming obstacles with determination. The pilot program not only produced invaluable reform experience but also forged a lasting spirit of reform.

At the very start of the pilot program, the State Council established the Leadership Group for the Reform of the Employees’ Medical Insurance System, with State Councillor Peng Peiyun serving as its head. Several deputy ministers and deputy directors-general from key ministries were appointed as members.

I deeply admire the working style of last-generation revolutionaries like Peng. She approached medical insurance reform with remarkable diligence and meticulous attention to detail. Under her leadership, the team operated with exceptional democracy, balancing perspectives from various departments while actively soliciting input from hospital directors, academic experts, employee representatives, and others. Everyone had the opportunity to fully express their views.

Through multiple rounds of consultation and deliberation, the team ultimately reached a series of consensus decisions.

From what I recall, Peng conducted at least eight inspection tours to the Two-Jiang pilot sites, and I accompanied her on five or six of these visits. Although Zhenjiang and Jiujiang are home to many renowned scenic spots, she did not visit a single one—each trip was strictly devoted to research. Our typical routine consisted of daytime field surveys and evening meetings, with our main “pastime” being a brief after-dinner walk around our accommodations.

Peng made another seminal contribution: from the very beginning of the Two-Jiang Pilot, she firmly opposed creating a dual-track system for employees’ medical insurance, rejecting the separation of enterprise workers and government/public institution staff into different schemes, unlike the approach taken with basic employees’ pension insurance. Throughout numerous reform discussions on the Two-Jiang Pilot, she consistently advocated for a unified basic medical insurance system for all urban employees. This principle was ultimately enshrined in the landmark Document No. 44 [Decision of the State Council on Establishing the Basic Medical Insurance System for Urban Employees].

At the same time, I deeply admire the grassroots medical insurance workers in Zhenjiang and Jiujiang. They truly forged a new path by “crossing the river by feeling the stones,” bravely confronting countless unknowns and challenges. Whether under scorching heat or biting cold, they tirelessly went door to door to enrol residents in the insurance program. Often, they had to explain policies repeatedly, always with remarkable patience.

Their dedication is perfectly captured in a saying I still remember: “Worn-out shoes, worn-out lips, and worn-out mianzi/face.” This vivid phrase reflects their frontline efforts in implementing pilot reform programs within enterprises.

The grassroots medical insurance workers’ efforts and innovations not only benefited local residents but also provided valuable experience for advancing medical insurance reform nationwide. Reforming medical insurance systems is a global challenge, yet pilot cities—especially Zhenjiang and Jiujiang—have boldly explored new approaches under the guidance of the State Council. Zhenjiang and Jiujiang, in particular, have served as pioneers in China’s medical insurance reform and deserve full recognition.

Zhenjiang, Jiujiang, and most of the expanded pilot cities can be regarded as courageous pathfinders, continuously exploring and testing various approaches until they found the right path. Their efforts accumulated invaluable experience that helped shape China’s medical insurance system and prepared it for nationwide implementation.

All these efforts culminated in the 1998 State Council’s “Decision of the State Council on Establishing the Basic Medical Insurance System for Urban Employees”—known as the historic “Document No. 44” in China’s healthcare reform. This document established the fundamental framework for employees’ medical insurance, laying the foundation for the system’s eventual expansion to universal coverage. With this milestone, China’s healthcare security system entered a new phase of development.

Reflection: Beyond the Two-Jiang Pilot

History is a mirror. When we study history, we must not only learn what happened but also understand why. For example, recent discussions have raised the question: Why did China choose a socialized health insurance system? The answer lies in the deep historical context.

In the mid-1990s, SOEs were undergoing difficult reforms, with an urgent need to improve overall efficiency, and government finances were tight. Learning from the experiences of developed countries such as those in Europe, Japan, and the United States, China chose the socialized health insurance model. This system, funded jointly by individuals, employers, and the state, ensured healthcare accessibility while enabling rational resource allocation, thereby avoiding the potential pitfalls of “free healthcare”.

To my knowledge, former planned economies in Eastern Europe also adopted socialized health insurance after transitioning to market economies. Of course, each country’s level of social health insurance funding, the contributions from employers and employees, and the level of insurance expenditures vary, but the basic principles remain consistent.

Others argue that under the planned economy's employer-subsidised and state-funded health insurance systems, medical treatment was essentially “free.” If free healthcare was achievable in the past, why does it seem unattainable now? To address this question, we must revisit the foundational distribution theory of the planned economy.

Under the planned economic system, according to Karl Marx’s analysis in the Critique of the Gotha Programme, the distribution of labour’s proceeds to workers involves several deductions before the remainder is allocated. First, a deduction covers the replacement of consumed means of production. Second, a portion is reserved to expand production. Third, a deduction forms a communal fund for social insurance against accidents, misfortunes, and other contingencies. Fourth, part of the product is allocated to the general administration of society. Fifth, a share is set aside to meet collective needs such as education, healthcare, and other public services. Finally, a fund is established for the incapacitated. This sixth deduction can be understood as a social security fund for those who have lost their capacity to work, whether permanently, as in old age, or temporarily, due to illness or injury.

Therefore, under the planned economy system, although workers seemed not to contribute directly to pension and medical insurance funds, these costs were effectively deducted from their wages in advance, creating a fully state-funded security model. However, historical experience in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and China has shown that fully state-funded pension and healthcare systems are not successful models. Current challenges in healthcare reform do not justify a return to the old path.

Over the past three decades, China’s healthcare insurance reform has steadily deepened, achieving remarkable results. With socioeconomic development and growing public demand for better medical security, we must further advance medical insurance reform and strengthen the healthcare safety net to ensure people receive higher-quality and more efficient medical services. The journey of healthcare reform remains long and challenging.

The events and documents mentioned in the article have also been chronicled in detail in The East is Read’s earlier features: