Why a Legal Clarification on Social Security Shook China’s Public Debate

Deeper concerns about costs, fairness, and sustainability in China’s pension system.

When China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued a judicial interpretation in early August clarifying that employer–employee agreements to forgo social-insurance contributions are invalid, the text itself seemed straightforward. Yet the announcement set off a wave of online debate, forcing official newspapers such as People’s Daily and Economic Daily to issue unusual follow-up commentaries stressing that nothing fundamentally new had been created. The controversy reveals much about the state of China’s social-insurance system: the pressures on small businesses, the skepticism among workers, and the government’s effort to shore up a pay-as-you-go regime under demographic stress.

At its core, the interpretation—formally Article 19 of the SPC’s Interpretation (II) on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Labor Dispute Cases—declares that contracts or private promises between employers and workers not to contribute to statutory social insurance are void. Courts are instructed to uphold employee claims in disputes over unpaid contributions. Employers who later make arrears payments may seek reimbursement for any prior cash allowances given in lieu of contributions.

Article 19

Where an employer and an employee agree, or an employee makes a commitment to the employer, that social insurance contributions need not be paid, the people’s court shall determine such an agreement or commitment to be invalid.If an employer fails to pay social insurance contributions in accordance with the law, and the employee, pursuant to Item (3) of the first paragraph of Article 38 of the Labor Contract Law, requests to terminate the labor contract and to have the employer pay economic compensation, the people’s court shall grant support according to the law.

In the circumstances described in the preceding paragraph, if the employer, after making retroactive payments of social insurance contributions in accordance with the law, requests the employee to return the economic compensation already paid on account of the social insurance contributions, the people’s court shall grant support according to the law.

SPC officials emphasized during a press conference that the move is about harmonizing inconsistent court rulings across provinces, rather than adding fresh obligations. Indeed, China’s Labor Law and Social Insurance Law already stipulate that all formal employees must participate, with both employers and workers contributing.

China’s Labor Law: Article 72 The employer and individual labourers shall participate in social insurance in accordance with law and pay social insurance costs.

The interpretation, then, operates more like an authoritative reminder than a legislative innovation. The sharp reactions from many employers had less to do with the text than with its timing and context.

Many entrepreneurs, especially those running small and medium-sized enterprises, have seen margins squeezed by weak demand, rising costs, and intensifying competition in the years following COVID-19.

As Zoe Zongyuan Liu of the Council on Foreign Relations wrote in Foreign Policy in 2023

China’s statutory employer pension contribution rate remains relatively high, even after the central government lowered the rate ceiling six times between 2015 and 2019. The last rate cut in 2019 lowered the maximum rate from 20 to 16 percent, still higher than about one-third of the rich OECD countries and significantly above the rates in the United States (10.6%) and South Korea (9.0%).

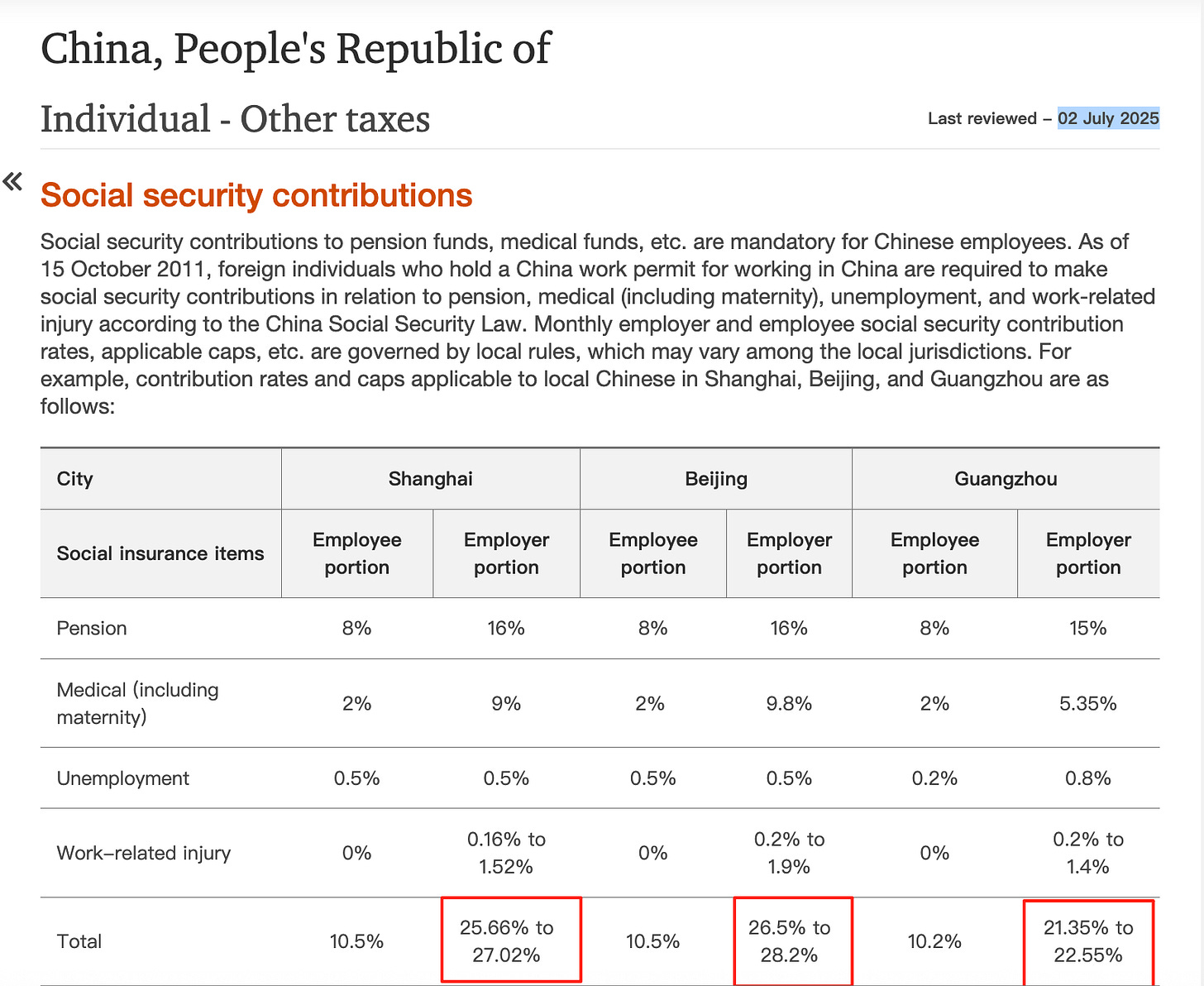

For employers, the obligation to contribute to social security, medical care, unemployment, maternity, and work-injury insurance feels burdensome. Even after the government lowered the employer’s basic pension rate to 16 percent in 2019, the combined outlays in large cities remain significant, often nearing 30 percent of payroll once ancillary items are added.

Another dimension is fragmentation. While China has made efforts to improve portability, the system remains balkanized. For employees, provincial governments still manage their own social-security pools, with uneven benefits and administrative frictions. Workers worry that contributions made in one place may not travel seamlessly to another, or that short stints in different provinces will leave them disadvantaged. Some employees themselves prefer cash in hand over deferred benefits. In practice, this has fueled the spread of informal “agreements” to skirt contributions.

Fairness concerns run deeper, partially a consequence of another type of fragmentation. But the exact details are complicated and confusing.

Traditionally, hundreds of millions of farmers and urban residents without formal employment did not pay social security contributions. Two pilot pension schemes for them, respectively, heavily subsidized by the Chinese government’s fiscal budget but also involving the beneficiaries’ relatively small personal contribution, began at the end of the 2000s. They were unified into a pension system for rural and urban residents - those who are not enrolled in the pension system for employed citizens - in 2014, continuously enjoying hefty fiscal subsidies.

According to a Xinhua report in July 2025, citing the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the Ministry of Finance, the Basic Pension Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents

惠及1.8亿多老年人,绝大部分是农村居民。

Covers 180 million senior citizens, most of whom are rural residents.

However, the payout under this 城乡居民养老保险 Basic Pension Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents varies by provinces but remains extremely limited, largely around 200 yuan ($30) a month. Beijing and Shanghai are wild exceptions at around 1,000 yuan ($140). That the figures are apparently too low by any standard and that most of the beneficiaries are rural residents, indisputably disadvantaged groups in China by any measure, has spurred a widespread sense of unfairness across China.

However, two counterarguments also seem valid. First, the beneficiaries historically paid very little into this Basic Pension Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents. Second, based on calculations done by a well-read Chinese blogger, pictured above, fiscal subsidies account for 82.2% of the payout, which is an enormously high percentage by itself and also significantly higher than the other pension system - 城镇职工基本养老保险 Basic Pension Insurance for Urban Employees.

According to the same Xinhua report in July 2025, in this pension system

主要惠及各类企业和机关事业单位退休人员,总量约1.5亿人。

The main beneficiaries are retirees from enterprises and government agencies and public institutions, totaling approximately 150 million people.

Here, despite being in one system, there are two categories of accounts - one for employees of government agencies and public institutions, and the other for employees of enterprises. The often cited figure is that the monthly pension for the first category is about 6,000 yuan ($837), and 3,000 yuan ($418) for the second category.

The public perception of unfairness seems more solid here. Only since the major 2015 reform, government employees and staff of public institutions have been paying social security contributions, much later than employees in the private sector, who essentially began in 1995. Yet, the state sector workers receive much higher pensions after retirement, a direct result of disproportionate fiscal subsidies, revealed by the Chinese blogger’s calculation - fiscal subsidies now underwrite 36.3% of state sector retirees’ pensions, and only 16.4% of - much lower - private sector retirees’.

The fact that a big part of current contributions by employees today are immediately used to pay current retirees—rather than accumulating in individual accounts—has only sharpened concerns among younger and poorer contributors that they are subsidizing better-off retirees, especially if current employees’ parents are under the Basic Pension Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents. They ask, as the meme on Chinese social media goes, why am I using my own money to support wealthier retirees in cities while neglecting my own parents in villages?

That current employees’ contributions are directly transferred to retirees also fuels the worry about sustainability against China’s demographic shift, with the working-age population shrinking and the elderly population swelling at an unprecedented speed.

This is why the SPC’s interpretation has been received less as a technical legal clarification than as a political signal. Critics online argue that enforcing mandatory contributions to the letter of the law could be the final straw for fragile businesses struggling in a slowing economy. In response, People’s Daily insisted that claims of a “new nationwide compulsory tax” were misleading, pointing out that the duty has long existed. Economic Daily similarly argued that the interpretation is not an expansion but a unification of judicial standards.

Yet the very need for these defenses underscores the delicate balance. If official media stress too loudly that the rule has always been binding, they implicitly highlight how widely it has been ignored. If they sympathize too much with struggling firms, they risk appearing to condone evasion of the law.

Beijing has hardly been idle in trying to reconcile compliance with sustainability. Beyond a 2019 rate cut for employers’ contribution to social security, authorities allowed temporary contribution deferrals during the 2022 slowdown, a policy that helped firms manage liquidity without dismantling coverage.

The central government ordered in 2017 that 10% of the shares of central and local state-owned enterprises (SOEs) be transferred to the central National Social Security Fund (misleadingly named in English, in my opinion) and local social security funds respectively. In March 2024, the Ministry of Finance told Xinhua that the transfer had been completed. More recently, policymakers have adopted a plan for gradual and flexible retirement-age reform, designed to lengthen contribution periods and slow the drain on payouts.

Together, these measures signal an awareness of the pressures, but the public remains unconvinced that the system will be sustainable when today’s contributors reach retirement age, on top of their perception of persistent unfairness, which the authorities have done almost nothing about.

For courts, the new interpretation closes a loophole that had fostered divergent rulings: from now on, “waivers” of social-insurance obligations are categorically void. For employers, this raises the legal stakes of non-compliance, making it riskier to strike off-the-books deals. For employees, it strengthens their hand in disputes, offering a clearer legal path to remedies. And for policymakers, it provides another reminder that the underlying system requires more than judicial clarifications—it requires deeper structural reforms that align contributions with benefits, reinforce trust in portability, and adapt to demographic realities.

The interpretation will take effect on September 1. By then, the legal clarity will be in place. What remains far less clear is whether the political economy of China’s social security—its costs, fairness, and sustainability—will prove equally manageable.