Wang Ou: Migrant workers, after the honeymoon

Sociologist & child of migrant workers shares stories of young migrant workers through marriage and parenthood—and finds where everyday lives collide with urban rules.

A young woman who once described her cheery days in Shenzhen later sits on a doorstep in a Guangxi village, exhausted, saying the happiest and brightest days of her life are behind her. Mothers leave before dawn while children are still asleep, or ask grandparents to take them out so they will not see the goodbye, dreading the day they return and the child no longer calls them “Mum”. The promise of the city fades once migrants begin to ask a simple question: not how to work there, but how to belong.

China’s cities have a way of making migrant workers feel welcome—right up to the point they try to bring a family into the picture. As long as the newcomers are young, single, and mobile, they can look almost indistinguishable from urban youth: earning wages, spending freely, dating, drifting between jobs, sampling the city’s pleasures in dormitories and urban villages. Then a child arrives, and the city’s welcome mat is suddenly pulled back.

Wang Ou, Associate Professor at the School of Sociology, Central China Normal University, who is also a child of migrant worker parents, turns his attention to the moment when youth gives way to family life: the same young migrants who look urban before marriage become intensely frugal and relentlessly hardworking after childbirth. The turning point, Wang argues, is not a sudden moral awakening. It is the moment the city stops treating them as individuals and starts treating their family as a problem.

China’s urban institutions welcome these young migrants as labour, not as families. Once children arrive, the barriers harden: homeownership becomes the ticket to school places, access to public services hinges on rigid eligibility rules, and education—supposedly the great escalator—too often channels rural children into lower-tier tracks. For migrant families willing to spend almost anything on their children’s futures, the system offers more places, but fewer ladders.

Wang follows these lives across multiple sites—workplaces, dormitories, and migrants’ home counties—and shows what that exclusion does to family strategies, gender roles, and emotional life.

—Yuxuan Jia

Wang delivered the speech on 21 September. The video recording and Chinese transcript were published on YiXi’s official WeChat blog on 25 November. The video is also available on YiXi’s official YouTube channel.

Wang has kindly authorised the translation but has not reviewed it.

农民工,何以为家

Migrant Workers: Where Do They Belong?

Hello everyone, I’m Wang Ou from the School of Sociology at Central China Normal University. My work focuses on migrant worker issues, a topic rooted in my own life story.

My parents left our rural home in Jiangxi Province to work in Shenzhen when I was very young, and I grew up as a left-behind child. Every winter and summer, I travelled as a little “migrant child” to visit them in Longhua, Shenzhen. I still remember spending an entire night on a coach, and arriving at dawn feeling as though I had crossed into another world.

Because of these early experiences, I knew what industrial parks, factories, assembly lines, and shift work looked like long before I understood them academically. I was familiar with urban villages, factory dormitories, and sub-landlords, meeting migrant workers from all walks of life.

So when I began my PhD and encountered labour sociology, it resonated with me instantly. Since then, I’ve remained committed to studying China’s migrant workers.

01 A Confusion

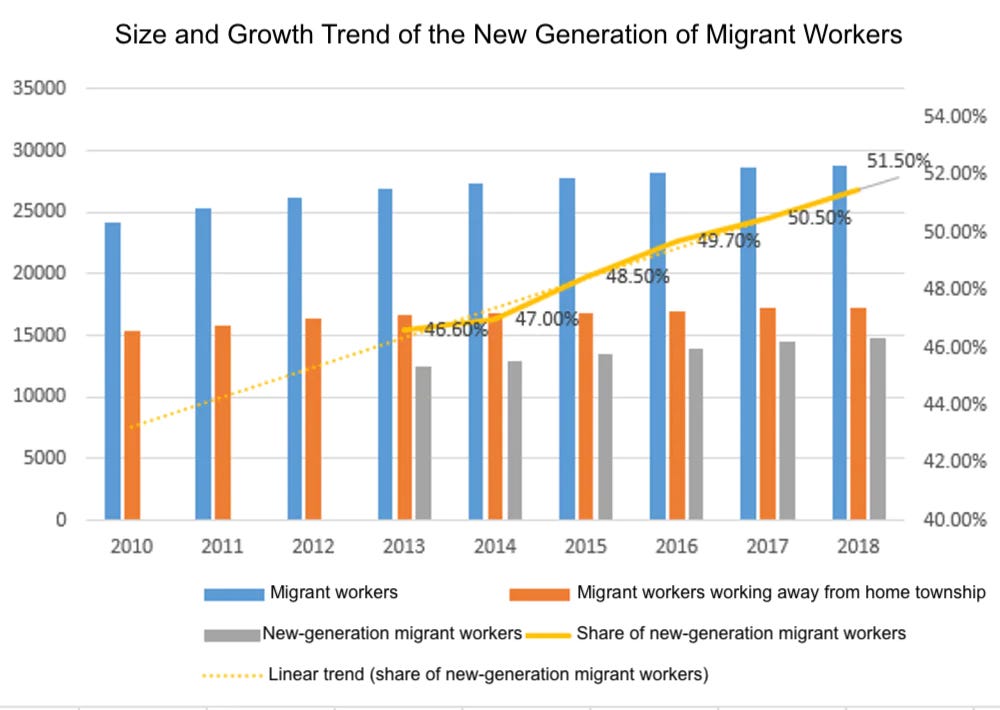

“Migrant workers” refers to labourers who hold rural household registration (hukou) but leave their villages to work in cities. This group emerged at the beginning of China’s reform and opening up, and its size has gradually expanded, reaching nearly 300 million last year.

With changes in China’s demographic structure, the migrant worker population has also undergone generational replacement. Older-generation migrant workers born in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s are gradually ageing, with some now leaving the cities; meanwhile, younger migrant workers born in the 1980s, 90s, and 2000s have become the dominant majority.

My own research focuses primarily on this younger generation, especially on how young migrant workers construct and maintain their families, and on the emotional issues embedded in these processes.

The reason I focus on this group is tied to a question that once puzzled me.

In 2010, the series of suicides among Foxconn workers caused enormous shock within academic circles, especially in the field of migrant worker studies. Most of the workers involved were very young, around 20 years old. In 2014, I encountered a widely cited survey on the new generation of migrant workers which argued that, compared with the older generation, younger migrant workers are more detached from the countryside and closer to the city; that their work ethic has weakened; that they are less able to endure hardship; that they frequently change jobs; and that most of their income is spent in the city.

At first, I found these conclusions convincing. The young workers I met in my parents’ workplace largely matched this impression.

But when I began conducting independent research, I found that young workers who had married and had children were nothing like this. They were extremely hardworking, willing to take overtime and night shifts; they lived frugally, reluctant even to eat out. When they gathered with coworkers, they bought groceries from the market and took turns cooking at home.

This led me to a major question: Why do members of this group undergo such a dramatic transformation after getting married and especially after having children?

Carrying this question, I began multi-site fieldwork across both rural and urban settings. I first went to the migrants’ work locations, as well as their living and consumption spaces, to collect data. Then I followed them back to their hometowns, gathering material in their home villages, townships, and county seats.

I intentionally collected migrant workers’ life histories and family histories. Each interview began with their family background: how they performed in school as children, when they first left home to work, what kinds of jobs they had taken, whether they had been in romantic relationships, what happened after marriage, and how they settled down and raised children. I also sought to connect each stage of their life course with the rural–urban institutional structures that shaped it.

Through this process, I observed turning points in their life trajectories; I witnessed the profound influence of family, especially children, on their decisions; and I saw the complex emotional struggles they carried.

02 Once Romantic

One of the first interesting phenomena I observed was this: in the years between leaving school and getting married, young and single members of the new generation of migrant workers display a strong sense of consumption autonomy and a pronounced desire for romantic relationships.

During my fieldwork in coastal industrial zones, I lived in urban villages where workers concentrated, as well as in factory dormitories. These areas were filled with places where young people consumed together—restaurants, shops, internet cafés, game arcades, KTVs, skating rinks, love hotels, small hotels, and so on. Workers earned money and spent it themselves, surrounded by peers of the same age, making emotional connections easy. For young women, especially, being far from the constraints of a patriarchal society gave them greater personal agency.

In one interview, a young woman worker named Jade told me:

“During those years in Zhongshan and Shenzhen, working was tiring, but the wages were mine. On my days off, I could sleep in, and when I woke up, I’d go shopping with my girlfriends. We ate good food, bought clothes, shoes, cosmetics, got our hair done, and got our nails done. We’d walk and walk until our legs couldn’t move, but we’d still keep shopping.”

Many men pursued her during those years. She eventually chose a young man she genuinely liked and who sincerely pursued her. She knew he was from a poor rural family in Guangxi, but what mattered to her was that he truly treated her well.

During our interview, she showed me photos of their trips together; her life then was colourful, full of emotion. This was very different from the older generation of migrant workers. Older migrant workers rarely experienced romantic love; like my parents and relatives who worked outside, their marriages were arranged through matchmakers before they ever left the countryside.

Later, Xiaoyu and her boyfriend rented a place together. Only when she was two or three months pregnant did they consider marriage. In this pre-marriage stage, their relationship with the city was positive: the city offered job opportunities and consumption spaces, they had autonomy over their spending, and romantic relationships flourished.

But once they married and started a family, they encountered a major turning point in their life course. At this moment, another face of the city immediately appeared.

For the new generation of migrant workers, marriage first brings the issue of housing; childbirth brings challenges of medical resources and childcare; children’s schooling brings struggles for access to education. All of these touch on the city’s provision of public services.

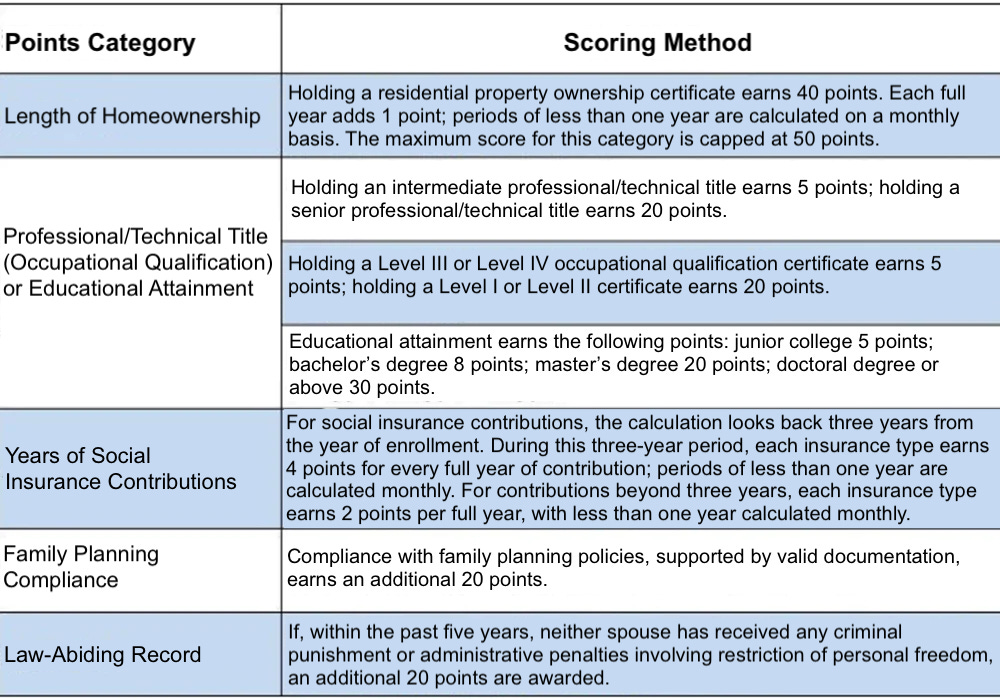

Take Kunshan, Jiangsu Province, one of my field sites. The city uses a highly calibrated points-based system to include or exclude migrant workers from public education. Points come from homeownership, education level, social security contributions, etc. For example, buying a home in a township gives 40 points; a junior college degree gives 5 points; each year of paying social insurance adds 4 points per category. Public school slots are limited and assigned by ranking—those who score high enough get in, those who don’t are excluded.

Like Jade, most young migrant workers, when faced with marriage, childbirth, and their children’s schooling, are forced to leave the city and return to their hometowns, even re-entering the patriarchal structures they once escaped.

A few years ago, I followed up with Jade again. I found her in a village about 50 kilometres from a county in Guangxi.

By then, she was a mother of two, and she had been left behind in her hometown for more than four years. Besides caring for her children, she also raised silkworms. Before dawn, she had to pick mulberry leaves, carry them back to feed the silkworms, clean their droppings, raise them until they cocooned, then sell the cocoons—repeating the same cycle. At the end of each year, she also cut and carried sugarcane—heavy manual labour.

When I saw her in the village, she was sitting on the doorstep, completely exhausted.

She told me that the happiest and brightest days of her life are behind her.

03 Mobility For the Sake of Children

Compared with my parents’ generation, the new generation of migrant workers values their children’s education no less than the urban middle class. They have a strong desire for their children to move upward, hoping they will attend high school, go to university, and eventually work in an air-conditioned office as white-collar employees. For this, they are willing to devote substantial resources.

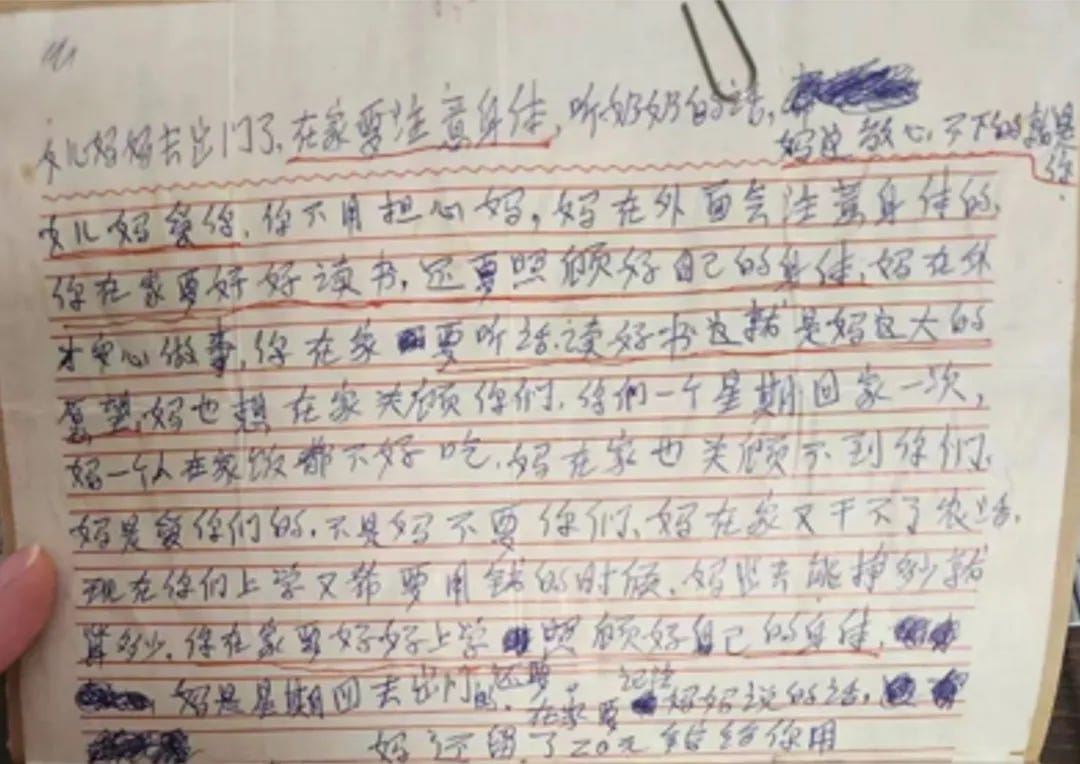

Ten years ago, while conducting research in an electronics factory in Kunshan, a female worker completed the questionnaire but refused to leave. Instead, she filled the blank space with dense handwriting, crying as she wrote. Later, I looked closely: she was explaining why, as a mother, she chooses to work away from home. Her only reason was to create better educational conditions for her child during a crucial stage.

But for this generation of migrant workers, the financial burden of education has become extremely heavy.

Over the past twenty years, migrant-sending areas in central and western China have experienced school consolidation policies—village primary schools were merged, and educational resources were concentrated in township centres. In one township I studied, which administers 28 villages and one community, by 2023, only two village primary schools, one township primary school, and one middle school remained. Enrolment in the two village schools had fallen below 100, and they were expected to be closed and merged soon.

As a result, migrant workers’ children must leave their villages from primary school or even kindergarten and either board, live with a parent who accompanies them, or be placed in left-behind children’s care institutions. Any of these options increases educational expenses.

More importantly, large numbers of apartments have been built in counties across central and western China. Local governments, using education as a tool to boost land finance, have concentrated high-quality educational resources around new housing districts, pulling excellent teachers out of old urban cores and townships, and tying school enrolment directly to homeownership.

Housing becomes the gatekeeper to education. To secure good schooling for their children, migrant worker families must buy a home (or attempt to rent and live there as “accompanying parents,” using personal connections to pass local checks, but that workaround is becoming much harder to pull off). In one county I studied, as many as 20,000 apartments were sold in a single peak year, with migrant workers being the main buyers.

When I conduct fieldwork in migrant-sending areas, my first stop is usually the county, and the first thing I see is row upon row of new apartments, plastered with slogans like “Good Schools, Good Homes.”

So, how much does it cost for a migrant worker to buy a home in the county? While staying in newly purchased apartments of migrant workers, I calculated the expenses carefully. In a county in southern Jiangxi, homes cost 6,000–7,000 RMB [$852-994] per square meter; in a county in western Guangxi, 4,000–5,000 RMB [$568-710]. A 100-square-meter shell apartment plus full fit-out costs at least 600,000–700,000 RMB [$85,215-99,418]. This is an enormous burden—often draining the savings of two generations and still requiring loans for ten or twenty years.

When interviewing mothers who accompany their children for schooling, I also calculated the monthly cost of living in the county: education fees, tutoring classes, hobby courses, snacks, toys, and daily expenses… For a migrant-worker family with a mortgage, monthly fixed expenditures reach 5,000–6,000 RMB [$710-852]. For migrant workers, the county has become a high-consumption place.

Under this financial pressure, male workers tighten the screws on themselves. Before marriage, they frequently switched jobs, preferring easier service work over assembly-line or construction work. But once they entered family life, they suddenly became extraordinarily hardworking, actively choosing heavy, long-hour, higher-wage jobs.

In reality, the delivery drivers in cities, the assembly-line workers in factories, and the construction workers under the scorching sun—once you look closely, most are married men working to support their families, especially to fund their children’s education. In these families, men are reduced to a narrow, highly economised role.

But the cruel reality is that over the past decade, wages for young male migrant workers have grown very slowly—sometimes even lower than those of the older generation. No matter how hard they work, they struggle to meet their family’s increasing reproduction costs.

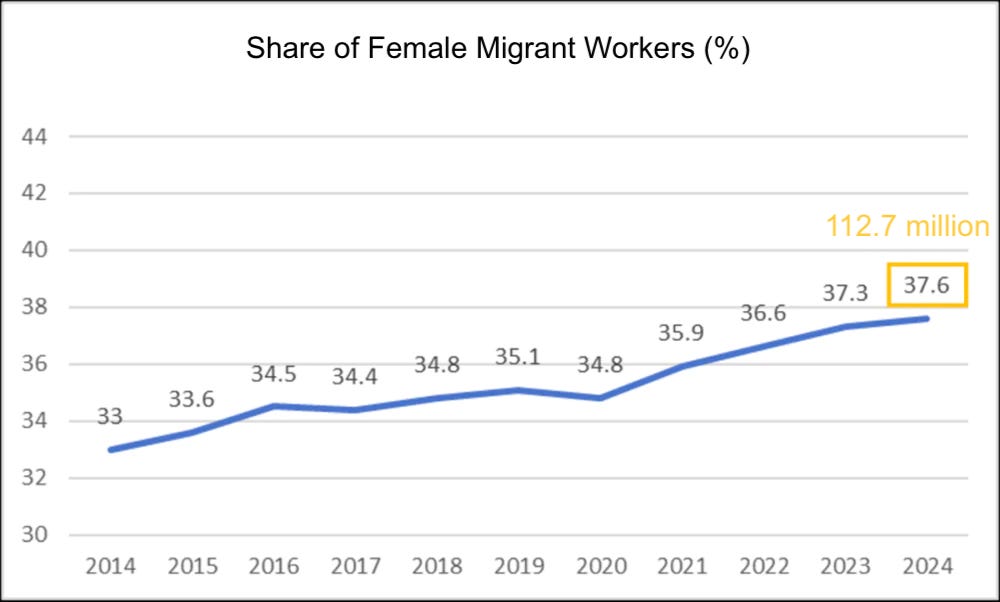

Thus, the economic pressure naturally shifts onto the shoulders of women workers. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the number of female migrant workers has continued to rise over the past decade, reaching 112.7 million in 2024.

04 Life as A Women Worker

My observations of female migrant workers are also connected to my mother’s experiences.

Growing up, I watched my mother devote herself to our family. Her life course can be divided into three stages: in her early years, she stayed behind to care for me and my younger brother; besides farm work, she worked at construction sites, rice-processing factories, lime plants, and other manual-labour jobs. Later, she followed my father to Shenzhen, where she worked for more than ten years, doing all kinds of jobs in the industrial zones, including physically demanding, undignified work such as loading and scavenging. After my younger brother had a child, her role shifted again—she became a caregiver for the next generation.

For this reason, my understanding of female workers differs from that of many gender researchers. I believe that looking only at gendered care work risks obscuring their economic contributions to the family. I place strong emphasis on what I call “economic motherhood”—recognising the financial labour female workers contribute to the household.

Across two generations of women workers, the way “economic motherhood” is practised looks markedly different. My mother’s generation stayed in the village longer, usually waiting until their children were relatively independent before leaving for work.

But among the new generation of female workers, I observed a far more urgent pattern—they are in a hurry to leave home and work, sometimes within a year of giving birth, or even sooner. One elderly left-behind caretaker told me, “This baby’s mother left less than a month after giving birth; the child was raised on formula.”

Why are young female workers in such a rush? Because they want to seize a window of opportunity to earn money between their child’s birth and the onset of the “critical educational period.” Different migrant mothers define this period differently; for some, it begins with primary school admission, for others, junior high. Regardless, they want to earn more before the critical stage arrives to improve their children’s educational chances, most importantly, by buying a home in the county.

They also mention other reasons. Some women said, “If only the husband works, with so many mouths to feed, you can’t save money.” Others said, “Without a car and a house, my son won’t be able to find a wife; even if a girl comes, she’ll run away.”

The moment they give birth, they immediately start thinking about whether their child can get into a good school, and, if it is a boy, whether he will one day be able to marry. Many fear their son could end up as what people in China call a “bare branch”, a colloquial term for a man left out of the marriage market. This anxiety is rooted in the widespread difficulty many rural young men face in finding spouses today. Once they have a son, mothers feel a pressing obligation to start preparing for his future marriage and the costs of setting up a household.

Under this pressure, many women leave for work while their children are still very young. The most common arrangement is for couples to take factory jobs together, seen as the steadiest and most dependable option. With overtime and shift work, they might bring in around 10,000 yuan [$1,420] a month between them. As the service sector has grown, some women also take jobs as waitresses, shop assistants, domestic workers, or food-delivery riders.

During my research in Guangxi, I came across something that surprised me greatly: many young women followed their husbands to construction sites in Beihai, Shenzhen, or even further away. These young women—who once liked dressing up and looking pretty—were covered in dust, binding rebar, mixing cement, and painting walls, all to earn a little more money.

Naturally, women working away from home face intense emotional pain.

When I first began researching Kunshan’s industrial district a decade ago, I was inexperienced and often asked women workers the same question repeatedly: What was it like when you left your child? How did the child react? Each time, they would start crying without realising it. Later, I learned that what they feared most was returning home only to find their child did not call them “Mom,” or avoided them like a stranger; and just when they finally reestablished closeness, it was time to leave again.

When do they usually leave? Early in the morning, when the child is still asleep, or they ask the grandparents to take the child out to play on purpose. If the child realises the mother has left, they cry uncontrollably. This tearing of the mother–child bond has become a deep emotional wound shared by both women workers and left-behind children.

As children grow and reach the critical educational years, significant divergence appears among young female workers. In families with fewer resources, women must continue working away long-term, and their children become left-behind children. Families with better means—able to buy or rent homes in the county—see women becoming “accompanying mothers.”

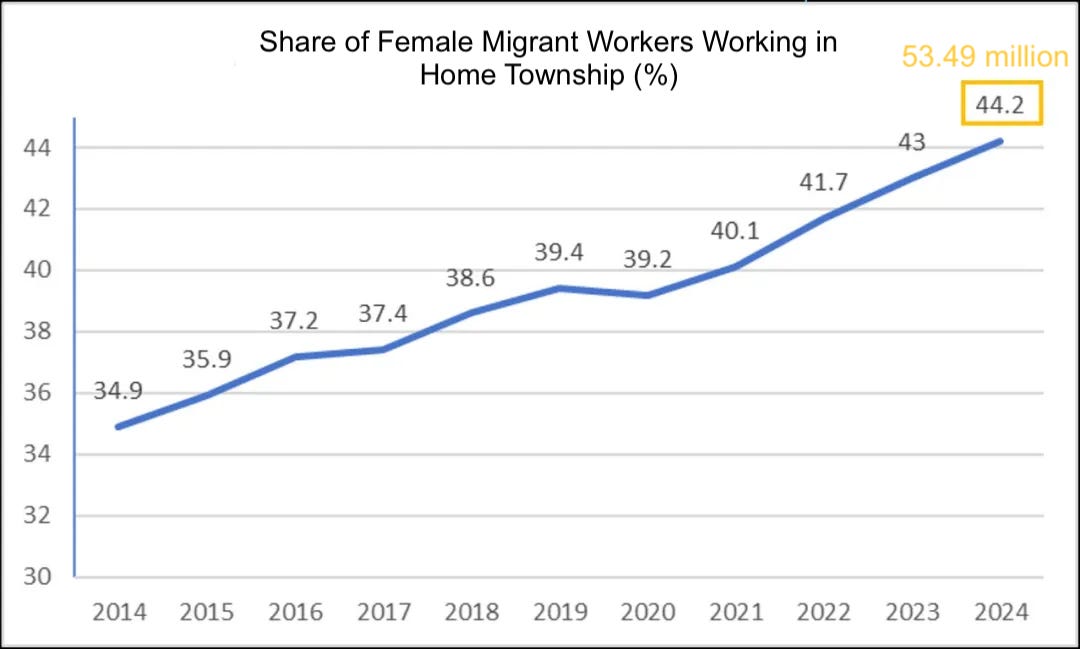

Data show that among locally based migrant workers, the number of women has risen rapidly. Over the past decade, the proportion has increased by nearly 10 percentage points, surpassing 50 million. A substantial portion of these are young mothers who returned home to accompany their children’s schooling.

But these mothers rarely accompany without working. They seek employment in county-level industrial parks, small workshops, supermarkets, restaurants, and other local workplaces.

In one county in southern Jiangxi, I observed the relocation of labour-intensive coastal industries to the interior. Migrant workers who had gained skills and small amounts of capital began taking orders from coastal clients but set up their production base in their hometown. They rented small storefronts or apartments near school districts, installed a few lathes or sewing machines, and aside from the owner couple, the workers were primarily accompanying mothers.

These workshops typically offered only informal employment, with no labour contracts, no social insurance, and no legally mandated holidays. Women earned very little, just over 2,000 yuan [$284] a month on average.

During periods of steady orders, they could somewhat manage both work and child care. But when urgent orders came in, everything became more chaotic. The boss pushed to deliver goods, and women worked overtime for ten or more hours a day, leaving them unable to look after their children. They had to rely on relatives or send their children to childcare institutions.

Thus, although they were “accompanying mothers,” they lived in a conundrum of being “at home yet absent.”

05 The Education Paradox

As their children grow older, do the circumstances of the new generation of migrant workers improve? Perhaps not.

After completing junior high school, the children of migrant workers face an important education policy: the “1:1 academic–vocational tracking ratio” [普职比, meaning that around half of students enter the academic track and half the vocational track —Yuxuan’s note]. Due to the urban–rural gap in education, a large proportion of rural children are assigned to vocational high schools, while only a small share manage to enter public academic high schools.

Because the new generation of migrant-worker parents places huge importance on their children’s education, some families spend additional money to send their children to private high schools.

When these children later sit for the college entrance examination (Gaokao), relatively few gain admission to top-tier universities such as 985 or 211 institutions. Some go straight into the workforce; others enter vocational colleges or private colleges [which are not the same as private universities in the West. These are generally lower-tier higher-education providers that sit outside China’s overwhelmingly state-run higher-education system. They often provide weaker teaching and fewer resources, and their degrees carry less weight in the job market. —Yuxuan’s note]. Before entering my PhD, I worked at a private college in Wuhan. The tuition was extremely high—on average, more than 10,000 RMB [$1,420] per year, and for more popular majors or arts-related programs, tuition could reach nearly 30,000 [$4,260].

This reveals a paradox:

The more disadvantaged a family is, the more they must pay for education.

Although education is expanding and the system appears to be providing more opportunities for rural children, what they ultimately receive are lower-tier slots within the higher education system—opportunities that require substantial financial payment.

Once their children finish school, migrant workers face yet another burden: buying homes for their children. Building a house in the village is no longer enough. Migrant families must purchase property either in the county or in the city, and also prepare for marriage expenses, including bride price.

During my fieldwork in Jiangxi, I met a woman worker named Kuang in a county industrial park. Her husband is a truck driver. In the past decade, overcapacity in the trucking industry has led to declining incomes. Their son had graduated from university and now works in Guangzhou, and has made it clear that he will not return to Jiangxi. Yet she still made a down payment on a county apartment for him, and she alone pays the more than 2,000 RMB [$284] monthly mortgage.

I asked her, “Your son may never return to the county. Why buy a home here?”

She said, “I feel more at ease if I buy it now. When he eventually decides to buy a home, I can sell this one and put the money together to help him with his down payment.”

This is a very typical mindset among migrant workers.

Of course, as their children have children of their own, these women’s roles shift yet again to become caregivers for grandchildren. As their parents-in-law age, they also shoulder eldercare responsibilities.

Over more than a decade of studying new-generation female migrant workers, my research shows that their entire lives are spent meeting the family’s different stages of economic and caregiving needs. Their life trajectories turn and bend with the demands of the household, and they sustain the family through their continuous labour.

06 A Taut String, A Fragile Home

Finally, I want to discuss the emotional entanglements within migrant-worker families. Many scholars emphasise the “resilience” of these families, but in my view, the opposite is closer to the truth. Under immense pressures of reproduction, migrant-worker families exhibit pronounced fragility—their economic “string” is pulled extremely tight, and it can snap with the slightest force.

The most dangerous situation is when husbands and wives work in different places. These couples once experienced deep romantic attachment and emotional intensity. But when they return to the very same urban environments where their intimacy first emerged—now for the sake of earning money—the tension between personal romantic impulses and family responsibilities creates powerful emotional conflicts, severely threatening family stability.

During my fieldwork, I saw far too many families break apart, leaving behind children raised only by grandparents and growing up without a father or mother. Once the marital relationship breaks or weakens, the entire family begins to fall downward—the parent who was previously in the county accompanying their child slides back to the township, and from there often sinks further into the lowest tier at the village level.

We may feel unfamiliar with migrant workers, or even hold stereotypes—imagining them as “Shamate youths,” “Sanhe drifters,” or people who only belong on construction sites or assembly lines. But in fact, they are all around us.

The first taxi I took upon arriving in Shanghai this time was driven by a migrant worker born in 1990 from a county in Shangqiu, Henan. He spoke with me along the way about buying a home and raising his child. Five or six years ago, he bought an apartment for 700,000 RMB [$99,418], with a monthly mortgage of 2,800 [$397]. His wife stays home to accompany their child, but the child’s grades are not great. He told me he never dares relax, because the monthly financial burden is so heavy.

Whenever I encounter stories like this, I cannot help but wonder: If these people—and their children—had been born in the city rather than in rural areas or migrant families, what kinds of life trajectories might they have had?

As someone who grew up in a migrant-worker family and now studies migrant workers, I hope Chinese cities become more inclusive. Cities have accepted migrant workers as labour, but what they need most is the ability to have a home in the city. If they could build a whole family life in the places where they work, then every story I shared today would look entirely different.

I hope Chinese cities can make more room for the family lives and emotional needs of migrant-worker households. That is the form of social progress I most wish to see, and it is the source of my enduring motivation for this research.

That is all I want to share. Thank you.

How much does this explain the low and declining birth rate that China is experiencing?

I wonder if migrant workers in Singapore, Malaysia face similar pressures. I doubt they can bring their families with them, and so have to leave their children behind in their countries of origin.