Three reasons for the rise of "new protectionism": Aaditya Mattoo's historical and macroeconomic perspectives

Part I of lecture by Chief Economist of the East Asia and Pacific Region of the World Bank at CCG on trends and future of global trade

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia from Bejing. The following is the first part of Aaditya Mattoo’s lecture delivered at the Center for China & Globalization (CCG) on January 17, 2024, themed “The New Protectionism: Origins, Implications, and Remedies.” The second part of the lecture and the subsequent dialogue with Mike Liu, CCG Vice President, will be published later.

In the following section, Aaditya Mattoo illustrates the three reasons behind the rise of what he terms the “new protectionism”:

1. Inequality: Trade is seen as benefiting nations overall but can lead to increased domestic inequality, favoring certain groups while disadvantaging others, like the industrial working class.

2. Risk: Heavy reliance on global supply chains is perceived as risky, with countries seeking to reduce vulnerability to external shocks by diversifying trade or localizing production.

3. Rivalry: Changes in global trade dominance lead to shifts in trade policies, with countries attempting to improve their relative standing in specific industries.

Aaditya Mattoo is Chief Economist of the East Asia and Pacific Region of the World Bank. He is also Co-Director of the World Development Report 2020 on Global Value Chains. Prior to this, he was the Research Manager, Trade and Integration, at the World Bank. Before he joined the Bank, Mr. Mattoo was Economic Counsellor at the World Trade Organization and taught economics at the University of Sussex and Churchill College, Cambridge University. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Cambridge and an M.Phil in Economics from the University of Oxford.

The event was covered by domestic news outlets including China Daily, Economic Daily under the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC), International Business Daily under the Ministry of Commerce of China, Beijing Daily, Phoenix TV, China Radio International (CRI) under China Media Group, and China’s Diplomacy in the New Era under China International Communications Group.

The full English and Chinese videos are available on CCG’s official WeChat blog. It is also accessible on YouTube.

***Following the publication of our article, Mr. Mattoo graciously reached out to us with suggested amendments for lexical accuracy, without altering the original perspectives. In response to this constructive feedback, we updated our publication with the revised content provided by Mr. Mattoo, ensuring the most scientific rigor and precision of the narrative.

— Yuxuan Jia, 11 March***

Thank you very much for inviting me. It’s a pleasure to be here. And I hope all of you will participate in this conversation. I know a lot of attention is being given to short-term growth rates, but this presentation is about longer term, structural issues, and focuses especially on the retreat from globalization that we have seen in recent years. We’ll talk about three dimensions of what I call the new protectionism. One is the genesis: why are we seeing a reversal of openness? The second is understanding the implications. And finally, about the remedies for the new protectionism.

We care about this retreat from globalization because we have seen that development, especially in this region, China, and Southeast Asia has been driven by trade. And trade has been driven by open markets with predictable rules. The new protectionism threatens both openness and predictability. And therefore, we as a development institution and you as a developing country, all have a stake in trying to find new ways in which we can address the new concerns.

New global protectionist measures

Let me begin by showing you what is happening today. First of all, there has been a big increase in protectionist measures. These include new tariffs, new export restrictions, new investment restrictions, a range of measures both on goods trade and on services trade.

The growth in trade relative to the growth in GDP

Second, consider how the relationship between the growth in trade and the growth in GDP is changing. It may not be an accident that this new protectionism is happening at the same time as the relationship between trade and GDP is changing. From the 1990s to the early 2000 was a period of hyper-globalization, where trade was growing much faster than GDP. The elasticity of trade with respect to GDP increased and peaked at about 2.5 at the beginning of this century. That means for every 1 percent growth in GDP, trade grew by 2.5 percent. After the Great Recession especially, the elasticity of trade with respect to GDP began to decline and is now lower than it has been for the last 50 years. Growth in trade is barely keeping up with the growth in GDP. We need to be concerned because the scope for specialization, the scope for diffusion of technologies, and all the other benefits from trade will slow down. One important question to is how far this decline is linked to the increased protection.

I will argue that there are three reasons why the new protectionism has emerged. First is the fear that trade contributes to inequality within countries even if helps them to grow; that is trade is regressive. The second concern is that trade is seen as risky. When you depend on other countries on things that you need, medicines, essential minerals or semiconductors, you worry that shocks, natural or political, will deprive you of access to those products. And the third problem is that instead of trade being seen as a win-win, where everybody benefits, trade is seen as rivalrous and contributing to shifts in industrial supremacy and economic power.

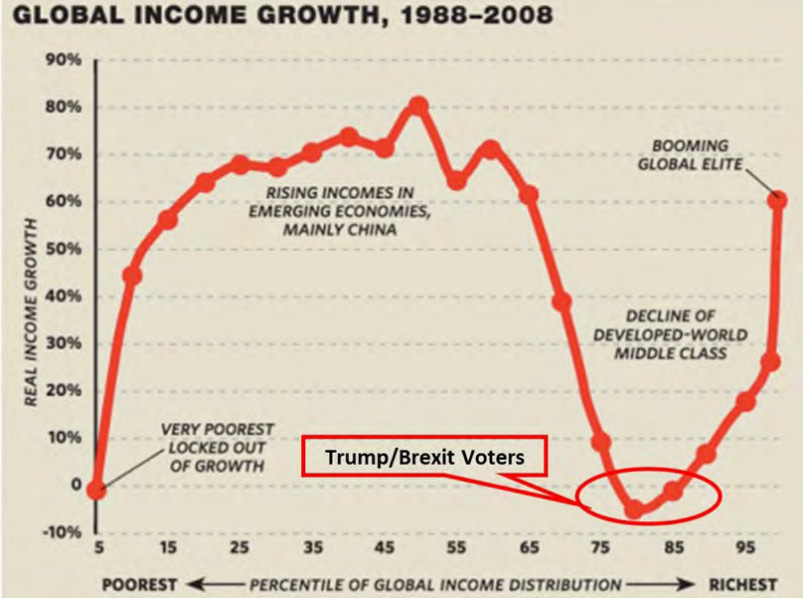

Growth in income by percentile of global income distribution

To illustrate the source of the inequality concern, let me turn to the famous elephant chart. Lakner and Milanovich looked at income growth in the whole world, from the poorest people, perhaps in South Sudan, to the richest people, perhaps in Switzerland. On the y-axis, you see how fast the incomes of each percentile have grown in the period of 20 years from 1988 to 2008. In the period of hyperglobalization, a country like China, whose population was in lower percentiles saw the fastest growth in income. In the rich countries like the U.S., the very rich, people like Bill Gates, saw their incomes increase a lot. The people who did not see their incomes increasing as fast were the industrial working class in the rich countries, who were located roughly around the 75th percentile of the global income distribution. Their incomes did not grow as fast because what they produced faced more competition both from imports from countries like China and Southeast Asia and from the domestic adoption of new automation technologies. The result was that the world become a more equal place but the rich countries became more unequal.

We have always known that trade creates inequality because some people win and some people lose. But because trade increases national income, it is possible to tax the winners and compensate the loser so that in principle everyone could be made better off. The problem is that globalization makes it hard to tax the winners because rich people and capital can relocate to jurisdictions where taxes are low. The winners are internationally mobile but the losers are not.

Changes in tax rates, 1980-2007

The consequences of this mobility are depicted in the picture above, which shows what has happened to tax rates in 65 countries in the world. Over time, because governments are competing to retain or attract investment and skills, they keep lowering the interest taxes on investment and the high earners. And who ended up paying most of the tax? The middle class. So the industrial working class in rich countries is suffering what is referred to as a “doubly whammy”: they do not benefiting as much from globalization because they face more competition from workers in other developing countries and they also end up paying more taxes.

The ideal solution would be to prevent this tax race to the bottom through international cooperation, and I’ll come back to it. But for the moment let us recognize that if you cannot compensate the losers through taxes and transfers, then you turn trade barriers. Trade barriers are far from the best way of improving the outcome, but it might be seen as the only feasible way. You start increasing tariffs to shield your workers from international competition. Thus point one is that even though trade has made the world on average better off and more equal, there has been a backlash because trade is seen to have contributed to inequality within rich countries and their governments have not been able to implement the better policies that would address the distributional consequences.

Let me now turn to the second concern: that trade is risky. Consider as an example the Tōhoku earthquake in Japan, that disrupted supplies of inputs that other countries depended on, including for cars. After the Earthquake, people became more worried about high-dependence products than less-dependence ones, that is they were more worried about products for which a large share of their imports came from Japan. The earthquake changed their assessment of risk and they reduced their imports from Japan where Japan was a relatively big source. But they did not stop importing or bring production home. They simply reduced their dependence on Japan by turning to other sources. It was reconfiguration rather than reshoring. Moreover, this was the response, not because of government policy, but because individual firms changed their risk assessment and chose to diversify. So the interesting point is that when there is a risk, individual firms calculate the risk and make a choice of how much to import from one place or how much to diversify.

Why does the government need to take measures? Imagine that each of separate firm or business independently considering costs and risks might choose to form import links or locate a subsidiary in China because it is much cheaper than other sources. The result of these individual independent decisions could lead to a collective outcome that most of a country’s imports come from China. So governments might in those circumstances say, "This is too much dependence on just one country. And we need more diversity.” But interesting analysis by Grossman, Helpman, and Lhuillier (2023), shows that it is not necessary that firms’ choices lead to under-diversification. Sometimes the result is over-diversification, because each firm wants to be the one that has access to an alternative source and can then make large profits if there is a shock to the primary source. The government’s problem would then be to induce firms to reduce diversification! The main point is to acknowledge that there are circumstances where firms face risks and do not optimally respond by diversifying or other measures. It may then make sense for the government to intervene, but the form of this intervention needs careful consideration and does not need to discriminate against any one source except to the extent that it is a source of over-reliance.

Number of trade-related climate policies in G20 countries

One of the biggest risks the world faces is climate risk. And here the question is that some of the trade restrictions that we are beginning to see now are related to climate policy. In some cases, trade restrictions are seen as necessary complements to national climate policies such as carbon taxes – to prevent leakage or loss of competitiveness when other countries do not take comparable action. In other case, subsidies are being used to encourage development or adoption of green technologies. But the subsidies are given to domestic industries conditional on using local content. Foreigners are not given comparable access to these subsidies. That’s what happens for example, in China, that’s what’s happening in the U.S.

How should we assess protectionist green subsidies?

The problem the world faces is the inadequacy of climate action. The best policy for climate action would be the whole world to agree, for example, to impose a tax on emissions or a subsidy for research and development. But the world is not cooperating to the desired extent. We don’t have the level of political support for action to reduce emissions to an extent needed to prevent a dangerous increase in temperature. Evidently insistence on local content to qualify for a subsidy or other discriminatory restrictions on trade are not efficient. They increase costs and reduce the real benefits of any subsidy. But the problem is, in the world we live in today if you don’t have protection, you wouldn’t have the subsidy. The politics in China, in the U.S., almost everywhere is such that you can only provide major climate support if it also helps the domestic industry. Protection is the price we are paying for climate action because the best climate action is not happening.

Consider now the source of the third concern: rivalry. Historically, changes in countries’ share in trade changes their international trade policy. This is an amazing chart and I hope you like it as much as I do. The figure shows over 200 years of trade share data from 1800 to 2016. The share of the United Kingdom in world trade was very high, nearly 50% in 1800, and then gradually it declined till it is now relatively low. The share of the U.S. in world trade gradually increased till it was as much as 20% of world trade. In the mid-19th century, a dominant UK induced many countries including China to open their markets, sometimes after a period of conflict. But it did not say "only for the UK" on a preferential basis. It said open for everyone on a nondiscriminatory basis. This laid the foundation for MFN, most favorite nation treatment, a pillar of the world trading system requiring each country to treat all my trading partners the same way. Throughout the 19th century, an era called Pax Britannica, the UK was the pillar of the multilateral trading system, practicing “free trade imperialism.”

It was only towards the end of the 19th century when there was catch-up by Germany and the U.S. that you heard conversations in the British Parliament about whether the UK should stay open. And finally in the late 1920s, when the British share of trade fell below 10%, Britain changed its policies. It instituted the system of imperial preferences with its colonies, which were obliged to trade on better terms with the UK than other countries.

Now, between the two World Wars, there was a period of retaliatory protectionism. But after the Second World War, it was the U.S. that emerged as the dominant trading country with a share of world trade greater than 20%. The U.S. helped negotiate the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which created the basis decades later for the World Trade Organization. This began the era that has been called the Pax-Americana, when America became the guarantor of the world trading system, and said, "Let us all be equally open to trade with each other." It was super dominant but did not use its power to seek privileged access.

When Japan started catching up with the US in certain industries in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a change in American policy. Japan was persuaded to adopt voluntary export restrictions in products like cars and semiconductors. But that was a temporary wobble. It was in 2008 that the US share in world trade fell below 10% and also roughly when China’s share in world trade became larger than America’s. It is an interesting coincidence because the UK also instituted imperial preferences when its share fell below 10%. That was the year that the Americans initiated negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP).

In 2001, the US had ushered China into the WTO. But eight years later, the United States was creating a new agreement that China would not be part of. When the U.S. was dominant and had significant bargaining power, it chose to play completely without discriminating. But when its relative dominance and trade started to decline, is when it retreated from MFN. Why is it that a country does not use bargaining power when it is very dominant, but uses bargaining power when it has become less dominant? I think that is one of the most interesting questions. But one reason for the recourse to bargaining tariffs is what is referred to as a “latecomer problem.”

The evolution of the share of trade in output and trade policy, 1990-2020

This is a picture about the evolution of trade and trade policy over the last 30 years. The 1990s, there was significant liberalization, unilateral and as part of free trade agreements. Eastern Europe joined the world trading system, India liberalized, China joined the WTO. The red line is the share of China’s trade in GDP. The gray line is the share of the world trade in world output. You saw a big increase in both shares until about 2008 during this period of liberalization. All this happened until the Great Recession, after which we see a flattening in the share in world trade in global output, and a major decline in China’s share of trade in GDP.

I would argue two things happened to change attitudes to globalization. China’s economic and export growth were much faster than expected. And China’s liberalization of its own market and import growth were much was slower than expected. China opened its markets a lot when it joined the WTO as the “entry price” of accession, which was economically desirable because China reformed. but its level of protection remained higher than that of say Europe and the United States.

The problem arises when one country has already reduced its protection a lot because it has been part of the trading system for a long time and another comes in late with higher levels of protection. Normally, in trade negotiations, countries say "I’ll give you the carrot of my liberalization if you give me the carrot of your liberalization.” But if I do not have much protection, I do not have much to give you. And that is part of the reason why the U.S. changed to say: I will threaten to use the stick of protection to induce you to give the carrot of your liberalization. That changed the rules of the game in a way that was not consistent with the rules of the WTO, which require unconditional MFN. That is one of the main reasons why the WTO is now in a limbo.

And it is happening now because the U.S. finds it less necessary to commit itself to playing by the rules than it did when it was much more dominant. When it was super-dominant, it had to reassure its trading partners that it would adhere to rules, otherwise they could simply walk away and economically disengage which would be costly for the US. Now other countries like China have a big stake in world trade and markets. They cannot credible threaten to walk away and that gives the US more space to exercise power.

Beyond trade diversion: the path to diagonal reciprocal cooperation

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia from Bejing. This is the second and concluding part of Aaditya Mattoo's lecture at the Center for China & Globalization (CCG) on January 17, 2024, themed "The New Protectionism: Origins, Implication, and Remedies." The first part of Dr. Mattoo's speech has already been published and his dialogue with CCG Vice President Mike Liu wi…

Aaditya Mattoo in dialogue with CCG Vice President Mike Liu

Hi, this is Yuxuan Jia from Bejing. Presented here is the dialogue between Aaditya Mattoo and CCG Vice President Mike Liu, along with Dr. Mattoo's Q&A session with journalists. This discussion took place at the Center for China & Globalization (CCG) on January 17, 2024, following Dr. Mattoo's lecture on "The New Protectionism: Origins, Implications, and…