The Story of Deflation: China in 1998-2002

Guan Tao, former Director-General of the Balance of Payments Department, State Administration of Foreign Exchange of China, on the "deflationary trend" more than 20 years ago

With China's announcement of a 0.3% drop in CPI in July, discussions have intensified over whether China has entered deflation. The following article, originally published in June in China Foreign Exchange, run by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) of China, presents a reflection on the causes, policy responses, and lessons of the 1998-2002 “deflationary trend” in China. It is also available in Guan Tao’s personal WeChat blogpost.

The first author of the article, Guan Tao, was former Director-General of the Balance of Payments Department of SAFE, China (2009-2015), and is now Chief Economist with BOCI Securities Limited, Co-Founder of China Finance 40 Forum (CF40), and Professor at Dong Fureng Institute of Economic and Social Development at Whuan University. The second author, Liu Lipin, is a Ph.D. candidate at Wuhan University.

Experts always debate whether China experienced deflation after the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. The different views actually stem from different definitions of the concept, whether it be the "single factor theory", which defines deflation as a general and sustained price decline; the "two factor theory", which adds contracting money supply; or the "three factor theory", which contends deflation should include sustained declines in prices, money supply, and economic growth rates.

However deflation is acknowledged, the sustained price decline in China during the Asian Financial Crisis is indisputable. Both retail price index (RPI) and consumer price index (CPI) embarked on a downward slide from October 1997 and February 1998, respectively. In 2000, CPI turned positive, signaling a possible easing in deflationary pressures, but turned negative again in 2001. From October 1997 to September 2003, RPI saw 68 months of year-on-year declines; from February 1998 to December 2002, CPI saw 39 months of declines.

The GDP deflator was negative for two consecutive years in 1998 and 1999, falling by 0.9% and 1.3% respectively, another indicator of widespread downward pressure on price in the country. Authorities later acknowledged this period as exhibiting a deflationary trend.

Causes of the 1998-2002 Deflationary Trend

Previous over-investment had resulted in excessive productive capacity.

After Deng Xiaoping's southern tour in 1992, an unprecedented investment fever swept the country. In 1992 and 1993, China’s total fixed asset investment grew by 44% and 62% respectively, real estate development investment grew by 117% and 165% respectively. CPI also surged from 6.4% in 1992 to 14.7%, further rising to 24.1% in 1994, showing signs of overheating. The government began to strengthen macro-control in mid-1993, implementing tight fiscal and monetary policies, and fixed asset investment growth fell sharply.

But previous duplicate investment had already led to prominent overcapacity, bringing great downward pressure on product prices. As noted in the government work report in early 1999, years of duplicate construction had led to serious overcapacity in most industrial sectors, economic structural contradictions had become more prominent, and the quality and efficiency of economic operation were not high.

Bank credit contraction led to slower aggregate demand growth.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) accounted for the vast majority of market share. Since state capital, in pursuit of equity returns, had high ex-ante efficiency losses and ex-post costs, certain individuals profited profoundly from SOEs. And because the net profit margin remained low for state capital, SOEs had to rely on lending from state-owned banks, leading to rapidly accumulating Non-Performing Assets (NPAs).

The Chinese government had repeatedly tightened control on bad debts since 1995, and its resolution was strengthened by the Asian Financial Crisis to strictly enforce commercial loan standards. As a result, the growth rate of bank loans fell from its peak (44%) in 1996 to a stable plateau below 20% after 1998. A large number of inefficient or loss-making SOEs were shut down due to lack of financing, while SOE reforms and job cuts led to an increase in laid-off workers. State sector employment decreased by 19.86 million in 1998, and continued to decrease by an average of 4.74 million per year from 1999-2002. Declines in income as well as expectations led to slower demand growth and negative price growth. Price declines further pushed up real interest rates, putting financing pressures on enterprises.

Economic transition and external shocks exacerbated weak demand.

China's economic transition accelerated after 1994, when the government introduced reforms in education, housing, and healthcare, etc. Increased uncertainty brought about by reforms, coupled with sharp rises in the prices of goods and services, changed residents' budget constraint, or, in other words, placed residents under liquidity constraint. The Chinese people were therefore motivated to save instead of consume.

While the Asian Financial Crisis brought considerable shocks to the global economy, the Chinese government's external commitment to not devalue the RMB further increased downward pressure on exports. From the second half of 1998 to the first half of 1999, China's export value stayed basically negative. The contribution of net exports of goods and services to GDP growth fell from 4.0% in 1997 to 0.5% and -0.7% in 1998 and 1999 respectively. Moreover, after the financial crisis, not devaluing the RMB in spite of general depreciation of Asian currencies led to domestic price declines so as to stabilize real effective exchange rate (i.e. export competitiveness), further contributing to the deflationary trend. From 1998 to 2002, the RMB's nominal effective exchange rate index, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) rose by 5.3%, while the actual effective exchange rate index fell by 6.4%.

Interaction of supply and demand factors formed a "deflationary spiral".

The aforementioned supply and demand factors resulted in a "deflationary spiral" that began in 1998 — previous duplicate investment and overcapacity led to falling prices and rising real interest rates, corporate profits and financing capacity declined, bad debts proliferated, and banks were forced to cut lending due to strict regulatory requirements; corporate finances deteriorated, investment and consumption demand slowed down, price declines and rising real interest rates persisted, and corporate revenues and financing exacerbated.

At that time, banks were "reluctant to lend" and enterprises were "cautious to borrow". It would take both macro policies that expand aggregate demand and micro improvements in corporate efficiency to overcome the deflationary trend.

Policy Responses to Deflationary Trends from 1998-2002

Timely policies to expand domestic demand.

China had seen rapid inflation as a result of economic growth since 1993. But the inflation rate was gradually brought down from double digits to single digits thanks to tight fiscal and monetary policies in 1995 and 1996. Having achieved a "soft landing" for the economy, the Chinese government further enshrined tight fiscal and monetary policies in the "Ninth Five-Year Plan" (1996-2000) in order to consolidate macro-control results.

However, the domestic and foreign economic climate worsened significantly following the outbreak of the Asian Financial Crisis. The Second Plenary Session of the 15th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in early 1998 pointed out that the fundamental response to the Asian Financial Crisis was to secure domestic economy, expand domestic demand, and tapping China's enormous market potential. At the end of 1998, the Central Economic Work Conference prioritized expanding domestic demand and opening up the domestic market. To this end, the Chinese government formulated pro-demand macro policies focused on residential construction and auto consumption. Fiscal and monetary policies also gradually shifted in a more expansionary direction.

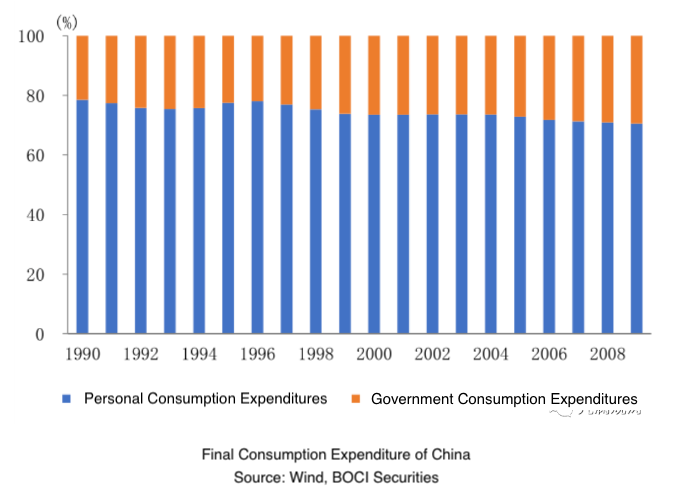

As the employer-based welfare housing program was abolished, and private property development, known as “commercial housing” kicked off, the investment and sales of residential buildings grew rapidly, increasing by 28% and 29% respectively from 1998 to 2002. In the meantime, auto consumption loans helped auto sales grow at an average annual rate of 17%. From 1999 to 2002, the contribution of Final Consumption Expenditure to China's economic growth averaged 68.9%, 18.4 percentage points higher than the 1994-1998 average.

Monetary policy shifted but had relatively limited effect.

Starting from May 1996, the People's Bank of China (PBoC) made multiple cuts on benchmark deposit and lending rates, which eventually fell by 9 and 6.75 percentage points respectively by the end of 2002. Starting from 1998, China officially adopted the “prudent monetary policy”, lowering the statutory deposit reserve ratio twice from 13% to 6%, and implementing measures such as canceling controls over the lending scales.

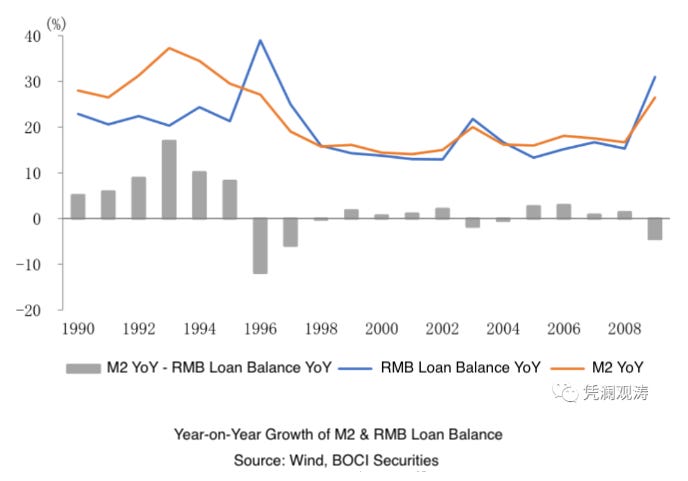

However, banks still appeared "reluctant to lend" under strict regulation, while issues such as high debt levels and overcapacity led to enterprises being "cautious to borrow". The stimulative effect of expansionary monetary policy on the real economy was also limited, partly due to consumers being less responsive to interest rates during economic transition. In 1997, the average monthly difference between the year-on-year growth rates of broad money supply (M2) and RMB loans of financial institutions was -5.7 percentage points. From 1998-2002 it was -0.2, +1.8, +0.7, +1.1 and +2.1 percentage points respectively. M2 growth remained higher than RMB loan growth, indicating unsmooth channels for transforming easy money into easy credit.

Proactive fiscal policy played an important role in stabilizing growth.

The Chinese government decisively prioritized proactive fiscal policies from the second half of 1998, with measures like issuing treasury bonds for financing infrastructure projects, adjusting tax policies to support exports, increasing expenditure in social security and science & education, and raising salaries for government agency and institution staff to enhance consumption power. From 1998 to 2002, the Ministry of Finance issued 660 billion yuan in long-term construction bonds, matched by 1.32 trillion yuan of bank loans, spurring total investment of 3.28 trillion yuan (in which 2.46 trillion yuan was eventually completed). By the end of 2002, the government debt ratio, according to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, had reached 25.0%, up from 9.1% at the end of June 1998. Fiscal boosts like these caused the contributions of capital formation and government consumption to GDP growth to rise by 5.4 and 3.1 percentage points respectively compared to 1994-98 averages.

Promoting SOE reform to improve corporate profitability.

As mentioned, inefficient state-owned enterprises were a core issue behind the “deflationary spiral”. Therefore, alongside demand stimulus policies, the government also introduced structural reforms. In 1997, the First Plenary Session of the 15th CPC Central Committee set targets to overhaul major loss-making SOEs within three years through reforms, restructuring, and strengthened management. By 2000, these SOE reform and turnaround goals were largely achieved. Fiscal policies played a key role, supporting SOE bankruptcies, consolidation reforms in key industries, and technological upgrades in key industries and enterprises. Debt-for-equity swaps were used to lower leverage and improve competitiveness among key enterprises. Between 1998-2002, profits of industrial enterprises dropped 17% before recovering to growth of 52%, 86%, 8%, and 21%.

Strengthening financial reforms and supervision

In November 1997, the first National Financial Work Conference called for transforming banks into true commercial entities, strengthening PBoC oversight, and accelerating state bank commercialization — as necessitated by the socialist market economy to “fundamentally resolve the problems in the financial field and open up a new phase of financial reform and development”.

On the one hand, the central bank's management system was restructured to reduce local interference. On the other hand, state banks were reformed by measures like the Ministry of Finance injecting 270 billion yuan into the Big Four banks [the Industrial & Commercial Bank of China, the China Construction Bank, the Bank of China, and the Agricultural Bank of China] through bond purchases to raise their capital adequacy. Four asset management companies [China Great Wall Asset Management, China Orient Asset Management, China Huarong Asset Management, and China Cinda Asset Management] were established to carve out non-performing bank assets.

Strengthening and improving foreign exchange management.

To maintain exchange rate stability while growing foreign exchange reserves, China strengthened the authenticity review of current account foreign exchange purchases and payments, further tightened restrictions on foreign exchange purchases under the capital account, and increased legislation and law enforcement efforts against illegal foreign exchange receipts and payments, all the while adhering to the principle of current account convertibility. From 1998 to 2002, the RMB remained stable at around 8.28 per dollar, while reserves increased by $146.5 billion U.S. dollars. This created conditions to maintain monetary policy independence.

Policy Lessons from Deflationary Trends

Fiscal policy was the focus, but monetary policy should not be neglected.

During the 1998-2002 deflationary period, China relied more on fiscal policy as the main macroeconomic lever for stabilizing growth and adjusting economic structure. In contrast, monetary policy had been effective for dealing with inflation, but was less impactful in deflationary conditions due to structural drags like low corporate efficiency, high debt levels, and increased household savings. This aligns with the Mundell-Fleming model insight that fiscal policy tends to be more potent than monetary policy under fixed exchange rates. However, monetary easing still provided meaningful support - interest rate cuts helped lower corporate borrowing costs and fiscal financing needs, enabling a policy mix approach to foster economic vitality.

Macroeconomic policies should be more forward-looking and timely.

By the time the Asian Financial Crisis had emerged in the second half of 1997, China's economy was already slowing and showing initial signs of deflation. Yet at the end of 1997, the Central Economic Work Conference called for "continuing to implement appropriately tight fiscal and monetary policies to curb inflation". Similarly the 1998 Government Work Report set targets like "economic growth of 8%, consumer prices rising within 3%... Achieving these targets can maintain the good momentum of high growth and low inflation". The monetary policy only shifted from “appropriately tight” to loose in 1998, and the fiscal policy from “appropriately tight” to proactive in the second half of 1998.

Structural reforms are key to resolving deflation.

Although loose fiscal and monetary policies do help recover of aggregate demand, structural reforms are still needed to address the underlying micro-level issues causing deflation. Looking at China's recent inflation figures, the Producer Price Index (PPI) has been declining year on year since October 2022, but the CPI is still on the rise. [Note, this article was released in June, 2023, but China’s CPI in June, 2023 recorded no change year on year, while CPI in July, 2023 dropped by 0.3% year on year] Although this doesn't necessarily indicate deflation, it points to oversupply and insufficient aggregate demand. In response, we must maintain strategic resolve and patience, steadily advance supply-side reforms to cut overcapacity while expanding domestic demand, and balance progress with stability..

Expectations management is important.

To prevent deflationary expectations during post-1998 price declines, the authorities have avoided publicly stating the domestic economy had entered deflation, and instead emphasized the existence of a deflationary trend. For example, the Monetary Policy Committee of the PBoC stressed in its Q4 2000 meeting that in the "Ninth Five-Year Plan" period (1996-2000), China not only successfully curbed inflation, but also accumulated experience in overcoming and reversing deflationary trends. Yi Gang, then Deputy Secretary General of the Monetary Policy Committee, put forward the "two characteristics, one accompanying" three-factor theory of deflation [易纲.治理通货紧缩与微观机制改革.经济研究参考,2000(10):3-10.]. However, Yi Gang later acknowledged that deflation had occurred during that period. [易纲 ,赵晓 ,范敏.罗斯福的“非常之责”与“非常之权”.中国改革,2004(06):20-23. See picture.]

China is also subject to the "impossible trinity".

The "impossible trinity" refers to how open economies can only choose two out of three policy goals: monetary policy independence, free capital movement, and a fixed foreign exchange rate. During the Asian Financial Crisis, China had no choice but to tighten and improve foreign exchange management to maintain a fixed foreign exchange rate and a growth-conducive monetary policy. But in recent years, the PBoC has ceased regular intervention, allowing two-way RMB fluctuations — a new normal providing a shock absorber benefit. The increased exchange rate flexibility has not constrained monetary policy, while reducing reliance on foreign exchange controls. We should continue to deepen market-oriented exchange rate reforms to provide institutional safeguards for better balancing development and security.