Professor takes on bureaucracy & vetocracy in Chinese local politics

Even praise from the state broadcaster did little to offset the disapproval of certain local leaders.

This is the true story of Yang Suqiu, who, after teaching literature and aesthetics at Shaanxi University of Science and Technology for nearly a decade, was temporarily reassigned to a government post through 挂职 guazhi, a practice in China of assigning officials or professionals within the state apparatus to temporary positions in different government departments in various regions to gain experience. For example, a local official, such as a deputy division-level or a technical officer, might be temprorarily assigned to work in a provincial or even national ministry, and vice versa; university professors may also take temporary posts in the government to broaden their practical experience.

From September 2020 to September 2021, during her guazhi appointment as the Deputy Director of the Bureau of Culture, Tourism, and Sports in the Beilin District, an administrative division of Xi'an City in Shaanxi Province, Yang managed to establish a district-level library from scratch—the Beilin District Library. She later wrote a best-selling book about this experience, 世上为什么要有图书馆 Why the World Needs Libraries, published by Shanghai Translation Publishing House in January 2024.

Ms. Yang and the publisher have kindly granted The East is Read permission to translate a section of the book recounting the aftermath of Yang's promotional article for the library before it opened. Her piece described her resistance to long-standing shady dealings between library managers and booksellers, where unsellable books were offloaded at a bargain, sometimes with kickbacks involved. The revelation of hidden practices caused a stir within the government; some officials appreciated the article, while others were enraged by the political damage to the government's image. Moreover, the sheer view count of the article greatly unsettled local officials, who closely monitored the comment section, fearing any negative public reaction. Yang soon found herself under immense pressure.

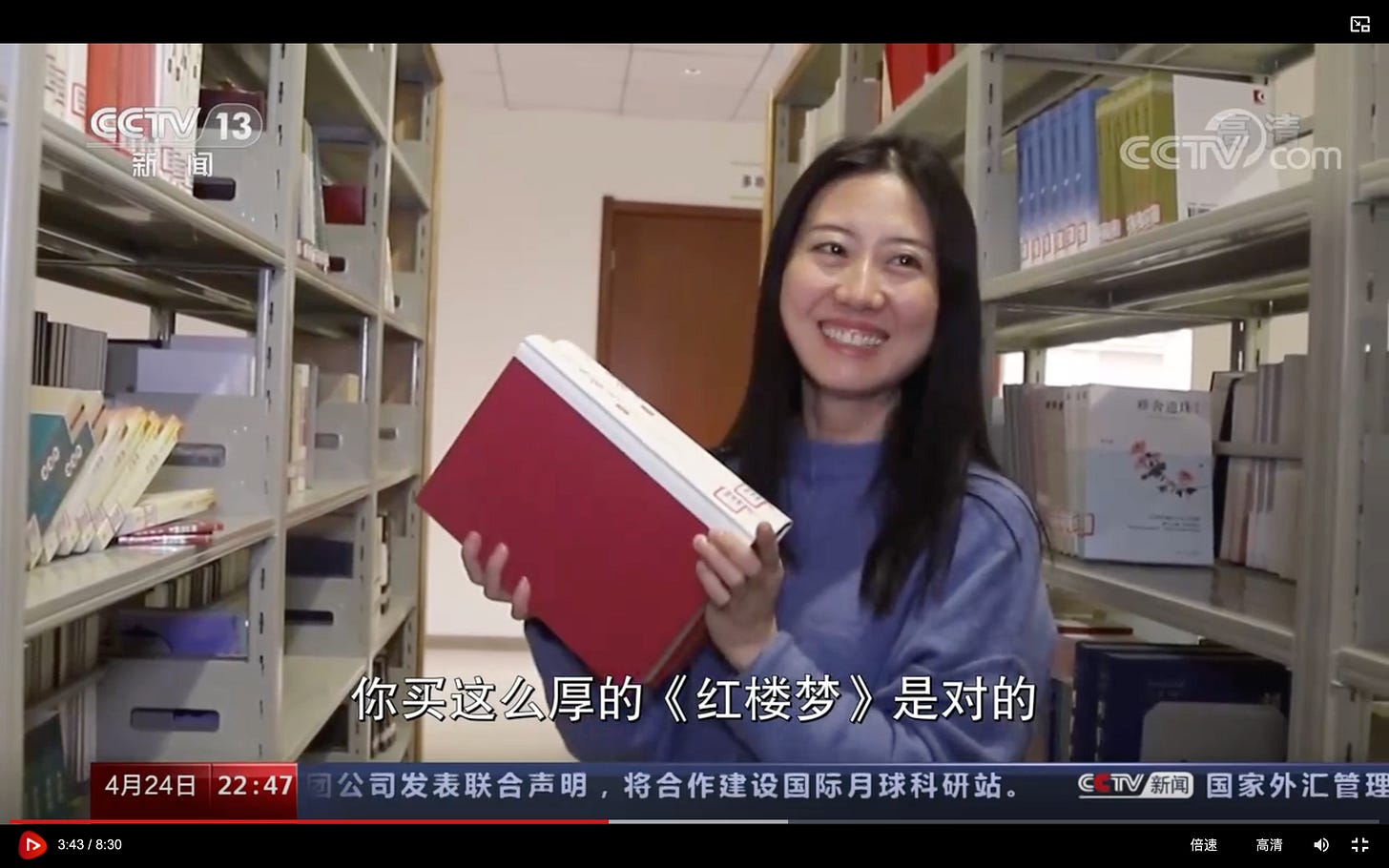

When China Central Television (CCTV), the state broadcaster, noticed the article and offered positive coverage, it slightly improved Yang's bureaucratic standing. However, local officials remained cautious. Immediately after the broadcast, they forbade the entire Bureau of Culture, Tourism, and Sports from sharing the CCTV link "in case any leaders get unhappy about it."

This case highlights the extreme risk sensitivity of lower-level Chinese officials. The power of vetos is clear: even though Yang's article had been reviewed and approved by several higher-ups, as well as the state broadcaster from Beijing, a few dissenting voices were enough to cause her significant trouble.

个人英雄主义

Individual Heroism

As the opening ceremony of the Beilin District Library drew near, Yunshu Company, the library's staffing provider, asked if I could write a promotional article to spread the news. If I were to write on the official WeChat blog of the Bureau of Culture, Tourism, and Sports, where I worked, the article would need to follow the typical red-tape style; if the article were to appear on larger social media platforms, my tone would need to be different. Yunshu Company wanted the former, but I preferred the latter. The point of publicity, after all, is to spread awareness, not just check a box. I started mulling over the style and angle for writing a piece on "a new library in downtown Xi'an" that would actually hook readers and inspire them to share it with others.

Over the past six months, I had seen the government achieve a lot, but the public was often unaware of that. The important stuff was often buried in dull, bureaucratic language that failed to catch anyone's eye. Mao Zedong once called out "stereotyped party writing"—that tired, cliched party speak—but it was still alive and well today, creating a wall between the government and the people.

I tried to keep my article in a jolly tone. The dramatic back-and-forth with booksellers—I wanted high-quality books from reputable publishers, while they persisted in offering unsellable, dirt-cheap books—fit perfectly in the first portion. The over-the-top, sycophantic phone call from one of the booksellers, trying desperately to salvage the deal, will definitely get a few laughs from my readers. My suggestions for improving the book selection guidelines, following a harsh review from an "expert panel" on my carefully curated book list, might stir up some debate if published, but I'm ready to take that on. I even included photos of my awful, hand-sketched construction plans for the library, unafraid to show our imperfections. We stumbled our way through building this library with zero experience, and I wanted every bit of it to be as raw and authentic as possible, making a real connection with the audience instead of just tossing out empty slogans.

Besides the article, I also needed to prepare remarks for the opening ceremony. Initially, I only had a rough outline in my head, planning to improvise on the spot—just like I used to when hosting talks at university. I've always found that skipping the script makes for a more natural flow and helps the audience feel more at ease. But that wasn't an option this time. My superior said, "We must avoid political errors. You will submit your script for record-keeping; no going off-script is allowed."

I did as requested and drafted the "Opening Ceremony Program"—who gives the opening speech, who unveils the plaque, who presses the start button, and who delivers the closing remarks. Then, I sent it around to the various higher-ups for review. They made their final edits by hand, drawing lines between program items and the officials' ranks—"President, Administrator, Section Chief, Director, Professor"—like a matching test.

And this is a very consequential test; getting it wrong could easily offend people. Yet, it was also strangely magical in that there was no "correct" answer. Suggestions from leaders at the bureau, district, municipal, and provincial levels were completely different. After six rounds of revisions from the panel of superiors, I finally settled on the directives of the highest-ranking leader to ensure no distinguished guest involved in the program would be displeased.

In my report to my superior, I briefly mentioned something about my selection of books. My superior responded, "It doesn't matter; whether your book list is good or bad makes no difference, just don't cause any trouble." Public cultural services are non-profit, meaning they don't generate economic benefits, so the higher-ups don't expect much from us—just avoid any incidents.

But the very next day, an incident did occur. My article, "We Spent Six Months Building a Not-So-Social-Media-Worthy Library in Downtown Xi'an," was published on the Zhenguan WeChat blog [Translator's note: once one of the most-read WeChat blogs in Shaanxi Province before being shut down for publishing a controversial article in September 2024] and quickly hit 60,000 views—far surpassing the usual numbers. Both the Zhenguan editorial team and I were surprised. Why were people so interested in a small library?

That afternoon, while others napped, I was too excited to sleep. Sitting on the couch, phone in hand, I refreshed the comments section every few minutes. Readers were buzzing, eager to visit the library and dive into the books. It seemed my attempt to sidestep the usual red-tape style had struck a chord. But just as I was savoring the success, I was suddenly summoned by government leaders for a talk. The article had caused a stir, and opinions within the government were split. The Beilin District Mayor and the Xi'an City's Culture and Tourism Bureau Director praised it, but others criticized it as "reckless and self-promoting." One outraged official even called to list five issues with my article:

Other districts were unhappy. If Beilin District Library's book list was boasted as so fantastic and exemplary, did that imply the book selections in other districts and counties were all subpar?

Experts who reviewed the book list were displeased. The article shouldn't have highlighted the problems with the book selection guidelines.

Government leaders were upset. The article didn't acknowledge the support from different levels of leadership, coming off as too much "individual heroism".

I shouldn't have exposed the under-the-table book supply rules, where booksellers offload unsellable or low-quality books to libraries at a bargain, sometimes offering kickbacks to library managers. This showed a lack of political awareness and disregard for the bigger picture.

What if negative comments arose? Such widespread visibility could provoke public sentiment...

It was only later that I found out my article had been promptly added to the watchlist of a government officials' WeChat group dedicated to monitoring negative public sentiment. This time, the group members carefully scrutinized the comments below my article for any indications of negativity. Thankfully, all the feedback was positive. However, due to certain dissatisfaction within the government, an urgent notice was issued by the bureau, banning further sharing of my article on social media, and any existing shares had to be deleted. I was also advised to apologize to some leaders. I laughed and said, "No problem, I'll go right now. The article is under my name, so I'll take full responsibility. Don't worry." Office Administrator Li looked at me in surprise.

Perhaps Administrator Li wanted to offer me some advice to help me navigate this setback, just as he had during past crises. Since joining the bureau, I've attended several "Party Committee Member Meetings," where tensions occasionally flared. Li never interrupted when someone voiced a strong opinion; he would patiently wait for them to finish and then calmly say, "I've listened carefully to your points. I have a small suggestion—it may not be fully formed, but perhaps you could consider this approach…" His ideas were often sharp and insightful, with an eye toward the long-term impact. His familiar presence—cropped hair, deep blue zip-up jacket, and sneakers—sitting composedly next to the Director along with his calm tone, provided a steadying influence at every meeting. Today, he turned to look at me but said nothing.

The Director and Ning, the head of the library, accompanied me on visits to the higher-ups, our large entourage a reflection of our sincere remorse. During the first visit, the leader was about to leave. Without accepting my apology, she walked briskly toward the subway entrance. The Director hurried ahead, struggling in stilettos, while I raced behind, throwing out apologies. The leader said calmly, "I'm getting on the subway; we'll talk later."

On the second visit, the leader pointed out three problematic sections in my article and walked me through how to revise them, using techniques I had never encountered when teaching writing at university. She was all solemn, saying, "You are politically naive. Your article doesn't openly criticize the government, but your views on the deals between booksellers and library managers could be twisted by people with ulterior motives to attack the government, potentially ruining both your political and academic future!"

I had been told this leader was a hands-on, well-respected figure, but the intense reaction I was seeing didn't quite fit that reputation. I studied her eyes, trying to figure out if her frustration came from personal conviction or external pressure. Was she genuinely worried about my future or merely acting out of fear? At that moment, I couldn't tell; she seemed sincere yet overly practiced, and I was confused about her true motives.

Inside, I felt calm. I believed my article, despite not adhering to red-tape formalities, had no serious flaws. Was it wrong to stand against shady deals with booksellers and push for better book selection for the people? My piece was rooted in integrity, not corruption, and I felt no shame in it, no matter where it landed. The criticisms from certain people could only be whispered in private, never aired out publicly. And that was fine. I could apologize a hundred times, showing perfect meekness in my appearance and language as if I were playing a repentant role on the stage, and go as soft as needed. After all, the books I bought for the community were already on the shelves, and my article had made the rounds. I had accomplished what I set out to do.

"Yes, yes, your criticism is absolutely right. I'm politically naive; I'll make improvements. Thank you for your kind and generous guidance," I said with deference, hoping to wrap up the situation. Internally, I blocked out their criticisms, steadied my emotions while walking out of the room, and prepared for the next day's opening.

Against all expectations, I received a call that evening from a stranger in Beijing, changing the course of events.

It was a Wednesday, and China Central Television (CCTV) reporter Zhang Dapeng was anxiously scrolling through various apps on his phone, seated on a plane. With World Book Day fast approaching, his team was scrambling to find a reading-related personality for their segment, "Person of the Week," a regular feature on the Newsweek program of CCTV, airing every Saturday. This week, it was Dapeng's turn to produce the segment, but he still hadn't found a suitable candidate. The clock was ticking—they had to film by Friday and edit by Saturday—a non-negotiable deadline. Time was slipping away, and by any means necessary, they needed to find someone for the feature.

As his team scoured various news platforms, Dapeng suddenly stumbled upon an article shared on Weibo, China's equivalent of X, titled "We Spent Six Months Building a Not-So-Social-Media-Worthy Library in Downtown Xi'an." Skimming a few paragraphs, he sensed potential, but the plane was about to take off, so he had to shut off his screen.

Up in the air, Dapeng couldn't stop thinking about the second half of that article, wondering if it could serve as this week's feature. As soon as the plane landed, he quickly read the rest. With each paragraph, he became more convinced it was the perfect fit. Themes like "book selectors" and "under-the-table book supply rules" were rarely tackled in the media, and they had just the kind of public interest hook his team was after. When he reached the final line—"The Beilin District Library in Xi'an opens on April 22, and you're welcome to visit"—he knew time was of the essence. It was already the afternoon of April 21. He hastened through the Beijing airport and contacted his team. There wasn't a second to lose.

That evening, Dapeng introduced himself as part of Bai Yansong's [Translator's note: one of the most recognizable anchors and journalists in China, known for his sharp commentaries] team at CCTV and mentioned he had just read my article and planned to film our opening ceremony the next day. To avoid "destroying my political future," I suggested he get approval from the relevant government departments before showing up with cameras. He reassured me, saying he had obtained my contact information through official channels, so there was no need to worry.

Hoping to steer clear of any impression of "individual heroism," I asked the camera operator to focus more on interviewing the various leaders and keep my appearance minimal. The operator disagreed, insisting that this would be a personality-centered documentary and that they intended to highlight the main subject. The team already had an outline in place, featuring footage of me, Ning, and the community, but not the leaders.

That day felt surreal with a rollercoaster of events. I had just finished humbling myself with apologies, only to be unexpectedly recognized for the very same thing later. During the day, as accusations flew, I built an inner shield, letting the criticisms bounce off with nothing more than a faint tingling sound. But that night, the sudden wave of support made me feel vulnerable, like warm water melting through ice. After hanging up the phone, a lump formed in my throat, and a wave of sourness welled up behind my eyes and nose.

News of CCTV's impending arrival had already spread among the leadership, stirring up some anxiety. They kept checking with me, "Bai Yansong? Is it going to be a positive report or negative exposure? Which program is it for, Newsweek or News Probe? The latter only features negative content. You'd better be sure. Don't agree to interviews recklessly!"

Upon learning that Bai Yansong was also involved with Newsweek, which features positive reporting, their tone softened. They instructed me that first thing in the morning, I needed to meet with the head of the publicity department for guidance on what I could and couldn't say in front of a CCTV camera. This, they stressed, was a matter of political stance, and I had to follow the rules—there was no room for error.

On the morning of April 22, the weather was refreshingly cool. After six months of hard work, the opening was finally here. My heart fluttered with a breeze of expectation, mixed with uncertainty stirred by CCTV's sudden visit. I couldn't help but wonder if this approaching cloud would bring about rain.

I arrived at the office a few minutes earlier than usual and found the Director already waiting for me. She accompanied me to meet the head of the publicity department in the northern part of the government complex. The Director and I stood while the publicity head remained seated, saying, "CCTV is coming, and we take this very seriously. As a guazhi official, you must focus on promoting positive energy, avoid criticizing society, and it's best not to mention any hidden practices or mention the term 'under-the-table book supply rules.'" Finally, the publicity department head shook my hand, saying, "We trust you'll keep the bigger picture in mind."

Back at the bureau, the hallway was calm as usual. A few staff members knocked on my door, whispering, "We've all heard—this is great news! You're finally getting vindicated. Make sure to look your best on camera today!" I'm not much of a makeup pro, so a colleague from the tourism section came with her tools to help me with eyeliner and lashes. Spotting my messy eyebrows, she ran over to the end of the hallway to fetch Li Min for a touch-up on "Director Yang's" brows.

Li Min works in the sports section, not directly under my supervision, so I'm not particularly familiar with her. She likes wearing shirts, which are neatly pressed each day before work. Her eyebrows are perfectly shaped, her blush subtle, and her mascara is always flawlessly applied—each lash standing out without clumping. She walked into Office 102 with her eyebrow razor and pencil in hand, saying, "Director Yang, you needed me?"

The tall Director Yang, a former basketball player, looked baffled and asked, "What do I need you for?"

Equally confused, Li Min replied, "Uh, to… fix your eyebrows?"

Our bureau had two Deputy Directors named Yang. Both, to keep it simple, were called "Director-General Yang." One, in Office 102, oversaw law enforcement in sports, culture, and tourism. The other was me, stationed in office 104.

Before long, the story of "Li Min going to fix the eyebrows of Director Yang in Office 102" made its way from one office to another, and soon, everyone was laughing—completely oblivious to the expression on the Bureau Director's face in Office 101. After finishing my makeup, I stepped out of the bureau, and the Director again reminded me, "Remember what the publicity head told you—keep the bigger picture in mind."

That ten-minute walk felt less like heading to my usual destination and more like stepping into some unknown "bigger picture." The trees lining South Street had grown lush, and from across the road, I caught sight of the sign for the "Xi'an Beilin District Library," now hanging prominently, unobstructed by leaves, and easy for both bus passengers and pedestrians to see.

Unfortunately, the workers had installed the red seal from Shi Ruifang, the calligrapher who had penned the sign, a bit too high, but there was no time to fix that now.

As I crossed the underpass and neared the library entrance, I spotted two camera operators waiting there, ready to start filming.

The escalator down to the B1 floor, where the library was located, was just twenty meters away, but I had to turn three corners to get there. Worried that readers might get lost, I had asked Ning to set up three directional signs, which were now clearly visible at each turn. I also noticed there were green arrows on the polished stone floor at each corner, which I hadn't instructed—Ning had clearly gone the extra mile.

Ning, wearing a light shade of lipstick and a suit with a lapel pin, spotted the camera behind me and quickly waved her hands, saying, "Don't let them film me!"

Many readers had already arrived. Several baskets of fresh flowers adorned the front desk—some from the library's suppliers, others from my students and friends. They had come quietly without giving me a heads-up. This was an official event, not a personal one; why were they bringing gifts? Familiar faces emerged from behind the bookshelves, calling out, "Suqiu, congratulations! Such a joyful occasion!" At that moment, I felt like a hostess at a countryside banquet celebrating either my son's wedding or the birth of my grandchild, bustling from one end of the courtyard to the other, gathering their well-wishes as if cradling them in my arms.

The heads of libraries from various provinces, cities, and districts arrived, and I greeted them with handshakes. However, one librarian ignored me and walked straight to his seat with a stern expression. I was puzzled at the time but later found out that my article was to blame. This librarian was furious after reading it because I mentioned that the discount for "under-the-table book supply rules" was around 80% off, while quality books received about 40% off. In previous years, he had reported to the finance bureau that his books were purchased at a "0% discount"—full price. He feared that if the finance bureau read my article, they might start digging into his past accounts, and if he came under scrutiny because of it, I'd be the one to blame.

The leader I had apologized to twice had assured me she would attend after receiving my invitation, but she was a no-show. Upon hearing that CCTV would be filming, she suddenly disappeared without any explanation. I called her, but my phone just rang endlessly with no answer.

The opening ceremony went off smoothly. The guqin piece Flowing Water [available via the link below] beautifully recreated the sound of a gurgling stream, and the children's poetry recitations filled the room with laughter. Even my impromptu jokes while hosting didn't cause any "political errors," and the leaders seemed content with their seating and the order of speeches. One leader even pointed at me and whispered, "CCTV is here to film her, not us."

Ning, who had been avoiding the camera, finally relented and sat down in front of it. She kept signaling me to sit beside her, insisting, "If you leave, I won't know what to say. I'll feel more secure with you around." Her knees were tense, and she kept turning to me for help: "Am I saying this right? How should I answer this question? Teach me, please." She seemed almost glued to me, and the camera operator subtly signaled for me to step away.

She tugged at my sleeve, but I still stood up to leave. When I looked back, she had only said a few words before starting to wipe her tears, reaching for tissue after tissue, finally covering her face and crying out loud. I wasn't sure exactly why she was crying, yet somehow, I understood. Leaning against a column in the hall, I couldn't bear to watch her shoulders shake. The past six months had been so much harder for her; she was the smallest cog in the hierarchy and the library's sole legal representative. While I was barging ahead, pushing things forward, there was always the chance that the risks would ultimately fall on her shoulders.

Ning said to me, "Please tell the producer to cut my part. They asked me to rate the library, and I gave it a sixty. Did I do wrong? Is that too low? Will the leaders blame me if they find out?"

Coincidentally, when I was asked the same question, I also gave it a sixty. First, the funding was tight, and we couldn't afford a designer, so the library's exterior wasn't appealing enough. Second, the book list I compiled wasn't good enough; my knowledge had significant limitations for sure. The producer kept asking about the "book supply rules" issue, and while I spoke a little about it, I couldn't go into depth—I had to "keep the bigger picture in mind."

Back in Beijing, Dapeng titled the episode "Community Book Selector," highlighting why such a small library was worthy of media attention—because book selection was deeply tied to the needs of the community. He stayed up late writing the script and started editing at dawn, feeling a bit of regret that Ning had cried for tens of minutes, barely completing any coherent sentences, making it difficult to include her in the program. He asked me, "Why did Ning feel so wronged? Why did she cry so heavily?"

I understood her well. When a distant stranger came to support us, I believed her feelings mirrored my own. But unlike me, Ning had a formal position in the local government, caught in a bind—wanting to speak out but too afraid to do so, which only made her cry harder. Dapeng said, "Then I'll make sure to protect both you and Ning." He then edited out the sensitive topics.

At 10:30 PM on April 24, my friends and family tuned in to CCTV-13, the channel where my program was aired, and leaders at various levels did the same. My friends eagerly shared the program, but the leaders had a much different reaction. As soon as the broadcast ended, they promptly prohibited the entire bureau from sharing the CCTV link, "Though this report is positive, we must remain cautious in case any leaders get unhappy about it."

The WeChat group of our bureau staff fell silent, though a few colleagues told me in private, "Seeing Ning cry made me cry too." I teased Ning, "Your face is all smudged from crying—people might think I bullied you!" She replied, "No way. You're the only one who truly understands what's behind these tears. When the reporter asked me to describe how we built the library, my mind just went blank—all I wanted to do was cry. I can't explain this constant flow of sadness. You're my rock. Only we understand what we've been through, and we can only lean on each other for comfort."

JD.com chickens out to masculinist "boy"cotts

JD.com, the world's second-largest online store and China's largest retailer, canceled its partnership with female comedian Yang Li just four days after announcing her as a brand ambassador, chickening out to hopping mad male netizens offended by her stand-up comedy four years ago.

Li Chen on Global Security Initiative

In April 2022, Xi Jinping, the Chinese President, proposed the Global Security Initiative (GSI).