Luo Zhiheng highlights continuous decline in China's macro tax burden, urging a new round of fiscal reform

Leading economist advocates targeted tax and fee cuts, more central bonds, adjusted distribution of revenues and commitments between central and local gvts, etc.

On March 13, 2024, the National School of Development (NSD), Peking University, in collaboration with Baidu Economic & Financial News, held the 68th session of the China Economic Observation Report event and launched the 30th-anniversary celebration of the NSD.

Several leading Chinese economists participated in the session, offering their assessments of China's current economic landscape and their visions for future development. Today's newsletter will feature Luo Zhiheng, the Chief Economist and President of the Research Institute at Yuekai Securities. Other speakers at the same event, including Justin Yifu Lin, Lu Feng, Xu Gao, as well as their Q&A session, have already been published.

Luo offers a nuanced assessment of China's fiscal condition, dissecting its current state, fiscal space, and strategic directions to enhance fiscal sustainability and support development.

Mr. Luo has kindly proofread our translation and made some edits. The video recording of the speech is available on the NSD's official WeChat blog, with the Chinese transcript published in another blog post.

A stocktake of China's current fiscal position and its prospective outlook

My presentation will focus on China's current fiscal position and its prospective outlook, addressing specifically three questions:

What is the true fiscal state of China? There are frequent misconceptions about China's fiscal situation on social media, making it necessary to clarify the true state of China's finances.

How much fiscal space does China have? Where does the fiscal space, if any, primarily lie? How can it be fully utilized?

Faced with the current fiscal situation and future development prospects, how should China respond to enhance fiscal sustainability and better support high-quality development?

Let me briefly share my conclusions on these three questions before detailed elaborations on each.

First, the present fiscal situation in China is best described as 紧平衡下的负重前行 "a burdened walk under tight equilibrium." This "tight equilibrium" reflects the temporary imbalance between revenue and spending, resulting in low fiscal capacity for local governments. This has given rise to the discontinuation of central heating services to residents, suspension of bus services, and delays and reductions in civil servants' pay in some areas. Nonetheless, it's crucial to recognize that local governments seek solutions to these challenges rather than "lying flat." They are striving forward by revitalizing existing assets and enhancing expenditure efficiency. "Tight equilibrium" is the reality, but the "burdened walk" forward is the attitude.

As for the second question, China does have additional fiscal space. This is determined by the nature of the economy, the monetary and financial environment, and the level of debt. However, it should also be noted that the fiscal space has indeed narrowed.

Firstly, with "public ownership as the mainstay and diverse forms of ownership developing together," China has substantial state-owned assets and resources, which can offset corresponding liabilities.

Secondly, China's monetary and financial landscape effectively complements its fiscal policies. The interest rates are on a decreasing path, facilitating a conducive environment and space for interest repayments.

However, it's crucial to acknowledge that fiscal space primarily exists at the central level and in the eastern regions which benefit from population inflow.

Answering the third question, looking ahead, given the financial strains and reduced fiscal space in certain regions, it is imperative to launch a new round of fiscal and tax reforms. This will not only address issues within the fiscal system but also provide a better fiscal and tax system foundation for high-quality development.

Next is my detailed analysis of China's current fiscal position and its prospective outlook.

The current fiscal situation in China: "a burdened walk under tight equilibrium"

Fiscal and monetary policies are generally believed to be the two potent and effective tools in macroeconomic regulation. However, my research increasingly reveals that fiscal policy tends to be more effective and more important during economic downturns.

Fiscal policy not only regulates the overall economy but also has a pronounced structural impact. Whether through tax and fee cuts or subsidies, fiscal measures are targeted and direct, impacting market entities with minimal intermediaries. More critically, fiscal policy also serves a reformative function; indeed, fiscal actions in themselves can be reforms. Reforms, development, and stability are all intertwined with fiscal policy. Fiscal measures clarify the relationship between the government and the market, as well as between central and local governments, fostering a scenario of proactive governance and effective markets.

Therefore, I believe that in the journey towards high-quality development, fiscal policy will play a more dominant role; monetary policy shall serve a supporting role, focusing on aspects of quantity, pricing, and structure. This involves coordinating with the issuance of fiscal bonds, increasing returns on treasury deposits, and facilitating the transformation of investment and financing platforms.

Fiscal issues have drawn significant attention from the market and society, especially in recent years. The fiscal situation in 2020 can be summarized in five words: "gloomy figures but fine budget." The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 led to an economic downturn and reduced fiscal revenue on the one hand, and on the other hand, necessitated increased spending on pandemic prevention and control, resulting in substantial pressure, hence the "gloomy figures." Nonetheless, the subsequent issuance of 1 trillion yuan [138 billion U.S. dollars] special anti-pandemic government bonds, along with their transfer to local governments, managed to keep the financial books in balance.

The fiscal situation in 2021 can still be summarized in five words, but reversed, now it's "fine figures but gloomy budget." This is because, in 2021, having managed to put the pandemic under control, the economy began to recover. Due to the low base effect, fiscal revenue data looked very promising. However, with no further issuance of special government bonds and a reduction in the intensity of fiscal policy, the fiscal status in China became challenging, necessitating careful budgeting.

From 2022 to the present day, China has generally been in a "tight equilibrium." This equilibrium exists not only between fiscal revenue and spending but also within fiscal spending, specifically, among the "three guarantees" (basic living needs, salaries, and local government operations), technology, and people's livelihoods. This suggests a shift from tightening the belts to getting accustomed to tight belts. Fiscal policy remains proactive but has shifted its focus towards improving quality and efficiency, emphasizing the effectiveness of spending.

What is meant by tight equilibrium? This can be observed in four aspects.

I. Fiscal revenues: Large-scale tax and fee cuts, coupled with the economic downturn, have led to a continuous decline in the macro tax burden.

From 2012 onwards, China has been grappling with a slowdown in economic growth, confronting both internal and external risks and challenges. In response, China implemented large-scale tax and fee cuts to reduce operational costs for enterprises, enhance domestic businesses' liquidity, and mitigate the effects of capital outflow induced by Trump's tax reforms.

Driven by both internal and external factors, these efforts culminated in the proposal "to cut overcapacity, reduce excess inventory, deleverage, lower costs, and strengthen areas of weakness" at the end of 2015, or the supply-side structural reforms. Among these objectives, "lowering costs" in fiscal and tax domains translated into large-scale tax and fee cuts, which, however, directly led to a reduction in the overall macro tax burden.

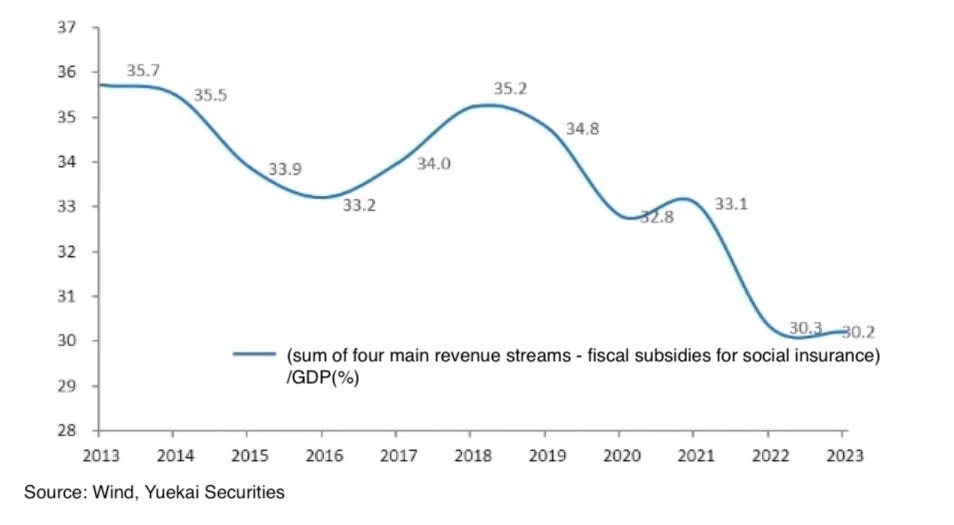

For most of the years leading up to 2015, China's fiscal revenue growth outpaced its economic growth. This dynamic shifted with the introduction of supply-side structural reforms, announced at the Central Economic Work Conference towards the end of 2015. Post-2015, the fiscal revenue growth rate has consistently trailed behind the economic growth rate. China's small-caliber macro tax burden (the ratio of tax revenue to GDP) peaked in 2015; by 2023, it has adjusted to around 17.2%, a decrease of about five percentage points.

Beijing’s revenue comes from four main revenue streams: tax revenues, land transfer revenues, surplus profits of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and social insurance contributions. An aggregation of these four sources, with careful exclusion of overlaps, is a broad indicator of the Chinese government’s fiscal capacity (fiscal revenue + government-managed funds). This sum is then divided by the GDP; the resulting ratio is the large-caliber macro tax burden, which stood at 30.2% in 2023, the lowest in the past decade.

The government typically considers two primary response measures when facing a decline in the large-caliber macro tax burden. The first strategy involves cutting fiscal spending, which would result in a retreat in public services. The second strategy is to increase debt to bridge the gap between declining fiscal revenue and ongoing expenditures. Last year, a notable decline in fiscal revenue was observed in eight provinces of China, including economically prosperous regions like Guangdong and Jiangsu, when compared to the figures from 2021.

Next, land transfer revenues. In 2023, most Chinese provinces reported a decrease in land transfer revenues compared to the pre-COVID year of 2019. For instance, before the pandemic, land in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province in southwestern China, was sold at over 100 billion yuan [13.8 billion U.S. dollars] a year, but this figure sharply fell to 10 billion yuan last year, marking a nearly 90% decrease. Harbin and Changchun, the capitals of China's northernmost provinces, experienced comparable declines. The sluggish real estate market has had a profound impact on government finances, particularly affecting local government revenues. Therefore, addressing the challenges in the real estate sector is crucial for ensuring fiscal and economic stability.

II. Fiscal spending: Diversification of performance evaluation metrics and the “fiscalization” of economic and social risks have broadened spending commitments and increased mandatory fiscal expenditures.

The Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee in 2013 stated, "Finance is the foundation and an important pillar of state governance. Good fiscal and taxation systems are the institutional guarantee for optimizing resource allocation, maintaining market unity, promoting social equity, and realizing enduring peace and stability."

This definition elevates fiscal policy beyond a mere economic concept to a key aspect of national governance, which inevitably integrates politics, economy, culture, society, ecology, etc. As a result, fiscal policy is expected not only to safeguard the welfare of the people, but also tasked with boosting overall demand, encouraging investment, and preventing and defusing major societal risks. This broad set of goals has consequently led to a tangible increase in fiscal spending, heightened mandatory fiscal expenditures, and an enlarged range of spending commitments.

The fastest-growing spending category in 2023 is social security and employment spending, which increased by 8.9%. This category has seen high growth rates in recent years, placing the share of social security spending on a continuous rise. The significant increase from 2013 to 2023 indicates a shift in China's fiscal spending structure from focusing on goods to prioritizing investments in human capital.

It is noteworthy that the growing pressures from an aging population have particularly heightened the national social insurance fund’s reliance on fiscal spending. Reflecting on China's demographic history, birth rates rebounded following the economic recovery in 1962. The number of newborns in 1962 reached 25.06 million, surged to over 30 million in 1963, and remained above 25 million annually until 1973. This means that 60 years later, the years 2022 to 2033 will be the peak period for retirements and pension disbursements, aligning with the retirement of this baby boom generation.

The 2023 national social security revenue reached 11 trillion yuan [1.52 trillion U.S. dollars], with 2.5 trillion [346 billion U.S. dollars] coming from fiscal subsidies. This accounts for 9.2% of total fiscal spending in 2023. This level of subsidy may crowd out other fiscal spending needs.

Additionally, interest expenses (for sovereign bonds + local general bonds) have risen, reaching 1.18 trillion yuan [163 billion U.S. dollars] in the 2023 fiscal spending. The spending on interest payments for local government bonds (local general bonds + local special bonds) has reached 1.23 trillion yuan [170 billion U.S. dollars].

Another noteworthy issue driving the increase in fiscal spending is the manifestation of various economic and social risks. In certain provinces, local governments have set up special relief funds in case of unfinished apartment buildings. This action signals the government's commitment to guaranteeing the supply of real estate, which, indirectly, stimulates market demand. The process of fiscal spending being used to bolster real estate sales is what I call the “fiscalization” of real estate risks. Additionally, in a scenario where a bank faces bankruptcy while still holding numerous customer deposits and financial products, the government would have to step in, providing compensation to affected parties to stabilize the financial system. This process is what I call the “fiscalization” of financial risks.

III. The above two challenges have resulted in a growing fiscal revenue-spending gap, necessitating more sophisticated coordination between fiscal revenue streams with a greater dependence on transferred funds and non-tax revenues.

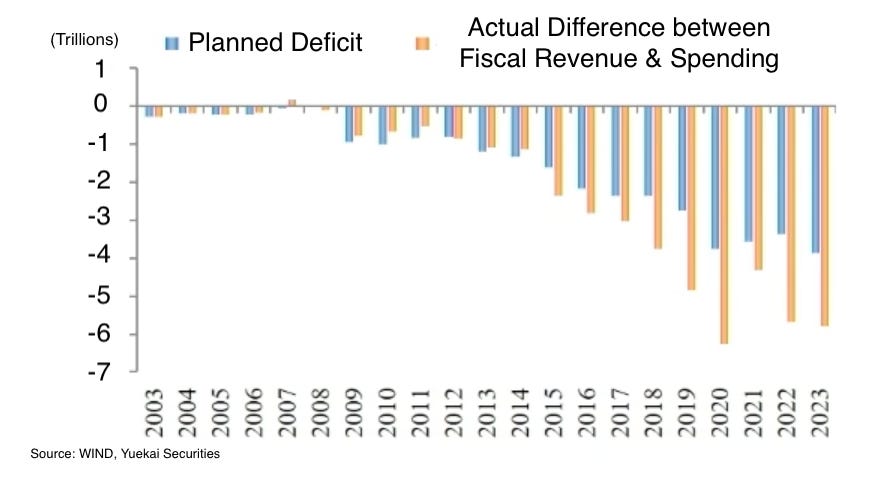

In 2023, China's fiscal revenue was 21.6 trillion yuan [3 trillion U.S. dollars], and fiscal spending was around 27 trillion yuan [3.74 trillion U.S. dollars], resulting in a shortfall of nearly 6 trillion yuan [830 billion U.S. dollars]. The 3.88 trillion yuan [537 million U.S. dollars] deficit, as outlined in China's 2023 Budget, accounted for part of this discrepancy, yet a gap of around 2 trillion yuan [277 million U.S. dollars] remained.

To address this issue, solutions included drawing from budgets for government-managed funds and SOE profits, in addition to carry-forward balance/cumulative surplus.

This indicates that future fiscal management will significantly depend on the effective coordination of fiscal revenue streams, including land transfer revenues and SOE profits. However, the likelihood of a decline in land transfer revenues poses a challenge to sustaining fiscal health.

IV. Although fiscal coordination has mitigated the fiscal revenue-spending gap, deficits remain a significant source of debt

Presently, local government debts are generally manageable. However, challenges persist, including a decline in the efficiency of special bond utilization, difficulties in repaying principal and interest on urban investment bonds, and issues related to the transition of urban investment platforms.

Currently, China's explicit debt stands at approximately 70 trillion yuan [9.69 trillion U.S. dollars], with the central government accounting for 30 trillion yuan [4.15 trillion U.S. dollars] and local governments contributing 40.7 trillion yuan [5.63 trillion U.S. dollars]. The composition of this debt sees national bonds constituting 40% and local bonds 60%. Within the local bonds segment, local general bonds account for 40%, and local special bonds for 60%.

This distribution highlights inherent risks and indicates the need for fiscal reform. The Central Financial Work Conference highlighted the importance of optimizing the debt structure of central and local governments. Emphasizing national bonds and local general bonds, which feature extended borrowing periods and reduced costs, will help elongate the debt cycle and decrease borrowing costs, thereby alleviating associated debt risks.

China’s fiscal space is influenced by three factors and is largely concentrated at the central government level and in the eastern regions, which benefit from population inflows

A country's fiscal space is determined by three factors: the nature of the economic system, the monetary and financial environment, and the level of debt risk.

Under its state-owned economic system, the Chinese government holds significant control over resources, enabling a higher debt capacity. In this context, deficits can be viewed as capital flows, while debts can be considered capital stocks. The real limitation comes from the obligation to repay principal and interest, particularly interest payments.

Currently, the low interest rates and favorable monetary and financial environment allow China to take on more debt.

Internationally, China's government debt is comparatively moderate. Efforts in debt restructuring have mitigated local debt risks, though hidden debts in some regions still need to be guarded against.

China's fiscal space exists mainly in two areas:

The central government.

Local governments in eastern regions that benefit from population inflows and robust industrial bases, offering better project reserves for efficient debt utilization.

Therefore, reforms can be made in two aspects:

Set special bond quotas based on potential projects to ensure funds are directed toward existing and new projects, rather than allocating quotas first and then searching for projects. This strategy will enhance the effectiveness of project financing.

Prioritize special bond quota allocation to the eastern regions that experience population inflows and have strong industrial foundations. These areas are more likely to utilize debt efficiently.

For the 2024 budget, the Chinese central government is proactively leveraging and optimizing the debt structure to create fiscal space for local governments. The government deficit is set at 4.06 trillion yuan [562 billion U.S. dollars], with the central government's deficit accounting for 82.3%. Additionally, the issuance of 1 trillion yuan [138 billion U.S. dollars] in ultra-long special treasury bonds indicates the central government's commitment to augmenting leverage and maximizing fiscal space.

I'd also like to emphasize the neutral nature of debt. Debt is neither a devil nor a panacea. The key is how it is used. The core of the debt issue lies in two aspects:

The structure and efficiency of debt use. Debt used for high-quality development and efficient investment is good debt. The expansion of the debt will not increase debt risk as long as it is backed by GDP growth or comprehensive fiscal capacity.

Whether the assets formed by the debt and the cash flows based on the assets match the repayment period of the principal and interest.

When these criteria—optimized debt structure, enhanced efficiency, and proper alignment of assets and cash flows—are met, the incurred debt can be considered good and unlikely to introduce significant risks.

A new round of fiscal and tax system reform is imperative: possible directions

The present fiscal situation requires well-thought-out measures. Despite some existing fiscal space, the available fiscal space is gradually narrowing. Identifying avenues to expand this space is critical and demands attention in the forthcoming round of fiscal and tax system reform.

In the short term, resolving the tension between revenue and spending is crucial. However, fundamentally resolving local government debts, ensuring fiscal sustainability, and fostering high-quality development necessitate medium to long-term reforms. I believe the new round of fiscal and tax system reform should serve two primary objectives:

Optimization of the fiscal and tax system itself.

Support for high-quality development.

Each era presents unique challenges. Back in 1994, when unchecked, overheated local investments were frequent occurrences, the pivotal concern was the central government's constrained macroeconomic control abilities. The tax-sharing reform in 1994 significantly boosted the central fiscal revenue share, from 22% in 1993 to 55% in 1994, establishing the current revenue-sharing framework. However, this reform left two critical issues unaddressed:

Division of spending commitments between central and local governments. While the revenue distribution issue saw resolution, the reform did not adequately tackle the distribution of spending commitments, resulting in a mismatch between revenues and commitments.

Reform of the sub-provincial fiscal system. [The original reform guidance stated, "Governments of provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the Central Government, and cities separately listed in the state plan shall formulate fiscal management systems for the prefectures and counties under their jurisdiction in accordance with this decision." This ambiguity has left room for inconsistencies at the sub-provincial level.]

Addressing these two legacy issues is paramount in the new round of reforms.

For the upcoming fiscal system reform, I suggest considering the following principles:

Clarify the government-market boundary. A clear demarcation between government and market roles is paramount. This approach is vital for preventing unchecked growth in the size and functions of the government, which in turn can alleviate fiscal pressures and burdens. Issues within the fiscal system are often rooted in governmental practices, making this a top priority.

The macro tax burden cannot get any lower. To navigate various challenges, a major country must maintain a certain level of macro tax burden. Hence, tax and fee cuts are recommended to pivot towards structural tax and fee cuts this year. By honing in on precision and effectiveness, and bolstering technological innovation and advanced manufacturing, such adjustments benefit both economic growth and the stability of the macro tax burden. Specifically, it's prudent to adjust tax categories that minimally affect the general population yet foster high-quality development. For example, broadening the consumption tax base to encompass high-end services, and elevating resource and environmental protection tax rates to encourage sustainable growth are viable strategies. It is also advisable to consider new domains like digital finance.

Adjust the distribution of revenues and commitments between the central and local governments. Redistribute certain commitments to the central government to lighten the local governments' financial load and enhance the efficiency of transfer payments. Currently, the central government's fiscal spending accounts for only 14% of the national total, a low figure by international standards. Achieving common prosperity and coordinated regional development requires concerted efforts beyond the capacity of individual provinces or cities. Thus, the central government should take on a more significant share of duties and spending commitments.

Boosting the transition of urban investment platforms is essential. Future urban investment platforms can be divided into three main categories:

Financing platforms. These are necessary in the short term, but efforts should be made to consolidate the number of such platforms as much as possible. Their debts should be systematically counted within government debt. In the long term, these financing platforms should gradually be phased out.

Urban utility service providers. These platforms still manage services including water, electricity, and gas, deriving revenue from government sources and direct consumer payments. However, they should no longer serve a financing role on behalf of the government.

State-owned capital operation platforms of industrial investment companies. These platforms should operate and engage in financing under fully market-oriented principles. Their survival shall depend on performance, with poorly performing entities facing bankruptcy.

Throughout China's economic journey, each year has been accompanied by difficulties and challenges, yet we have always achieved new developments by overcoming these challenges. Despite having mentioned many difficulties and challenges, I am confident that we can surmount these obstacles, thereby realizing a stronger Chinese economy.