Harry X. Wu warns declining Total Factor Productivity drags down China's economy

Peking University professor says TFP is essentially an institutional one—how to design an economic system that safeguards freedom and ensures fair competition through the rule of law.

According to the International Monetary Fund, Total Factor Productivity is a measure of an economy’s ability to generate income from inputs—to do more with less. The inputs in question are the economy’s factors of production, primarily the labor supplied by its people (“labor” for short) and its land, machinery, and infrastructure (“capital”). If an economy increases its total income without using more inputs, or if the economy maintains its income level while using fewer inputs, it is said to enjoy higher TFP.

Statistically, TFP is measured as a residual—the part of a country’s income that cannot be attributed to factor inputs such as labor and capital, which are easier to quantify. There are different measurements of China’s TFP in recent years. Eswar S. Prasad wrote in December 2023 that “For all the inefficiencies that pervade its economy, over the past few decades China has averaged a decent 3 percent growth in total factor productivity—which is growth that cannot be attributed to increased inputs, such as labor and capital, and is a general indicator of efficiency. But productivity growth has slowed to about 1 percent a year over the past decade.”

Harry X. Wu, a Research Professor of Economics at the National School of Development (NSD), Peking University, says China only saw strong growth of TFP between its accession into the World Trade Organization in 2001 and the global Financial Crisis in 2008.

Since then, Wu says, China’s TFP declined by 2.0% per year until 2012, after which the decline slowed down but remained in the negative range, marking a prolonged period of efficiency stagnation, and the various challenges facing China's economy today are a direct consequence of the unsustainable burden of the country's prolonged low efficiency over the past fifteen years.

The inability of "all policy efforts" to deliver significant improvements in TFP demonstrates, he argues, that China's policies aimed at maintaining economic growth and increasingly interventionist industrial policies were, in most cases, misaligned with Chinese firms' efforts to enhance efficiency.

On China’s official level, the significance of TFP seems to be increasingly recognized. For instance, "a substantial increase in TFP" was stressed by the top Chinese leadership in January 2024 as "a core hallmark" of the much-vaulted new-quality productive forces. However, Beijing - and mainstream economics textbook, according to Wu - seems to link the increase in TFP with only innovation based on scientific and technological progress, as evidenced by China’s ever-growing emphasis and investment in science and technology.

Wu says that’s wrong, because linking TFP with only technology assumes the elimination of “all institutional barriers that could cause efficiency losses, such as restrictions on factor mobility, price distortions, structural imbalances, and weak incentives for innovation. Additionally, it assumes the economy can seamlessly adjust to accommodate technological innovations.” That’s apparently not the case in the real world, or China.

Wu believes applying technology to achieve broader efficiency-enhancing effects can only be realised through comprehensive institutional reforms that adapt to these technologies. Such reforms must span a wide range of areas, including management practices, organisational structures, legal frameworks, policy measures, and political arrangements.

And from there, Wu says the only way for China to achieve this would be to adopt a comprehensive market-based system safeguarded by the rule of law and genuinely integrate into, maintain, and advance a rules-based global market system.

Wu made the remarks at an NSD seminar on September 13, 2024. The official NSD WeChat blog published the Chinese transcript of Wu's speech on December 10, 2024.

—Yuxuan & Zichen

伍晓鹰:中国经济转型内生的制度挑战

Wu Xiaoying: The Endogenous Institutional Challenges of China's Economic Transformation

The challenges currently facing the Chinese economy are fundamentally those of economic transformation arising from inherent institutional flaws—they are endogenous rather than exogenous. Such transformation is a significant hurdle that all developing economies must confront. Although developed economies may also face transformative pressures during periods of profound and disruptive technological revolution, the nature of these challenges is completely different. The success of China's economic transformation depends on a clear understanding of its essence and the boldness to devise appropriate policies. This subject warrants thorough discussion and deserves greater attention from both academics and policymakers.

In essence, the core challenge of economic transformation lies in improving economic efficiency, which ultimately comes down to enhancing total factor productivity (TFP). Regardless of the policies, management strategies, or adjustment mechanisms employed, without successfully raising TFP, economic transformation is out of the question. My analysis will begin by examining the nature of the challenges facing China's economic transformation, focusing on costs, labour productivity, and TFP, and then broadening the scope to institutional issues. Then, I will extend to the difficulties posed by reforms aimed at resolving these institutional challenges.

I. The Challenge of Rising Labour Costs is Essentially a Challenge of Labour Productivity

After the global financial crisis, the rising labour costs in China are often perceived as a major challenge. Many "economists" have echoed this sentiment, treating it as a problem that needs resolution, as though the purpose of long-term economic growth is solely to expand output rather than to enhance labour income.

However, the issue in China is not that labour income is increasing too quickly, but rather that its growth is excessively slow. This sluggish growth rate is so unusually slow compared to an undistorted economic scenario that it has significantly constrained consumption, thereby restricting production.

However, this is not the topic I want to focus on right now. What I wish to emphasise is that if rising labour costs are perceived as a pressure or challenge to economic growth, the real issue lies in productivity. This is primarily reflected in the relative growth rates of labour costs and labour productivity, specifically whether the increase in average labour productivity (ALP) can offset the rise in average labour compensation (ALC).

To analyse this relative pace, a particularly insightful statistical indicator known as the "Unit (Real Output to Nominal) labour Cost", abbreviated as ULC (ULC = ALC/ALP), can be utilised. It is important to stress that output must be measured in real terms (adjusted for inflation), while labour costs should be measured in nominal terms. Only by adhering to this approach can the issue be accurately observed and understood.

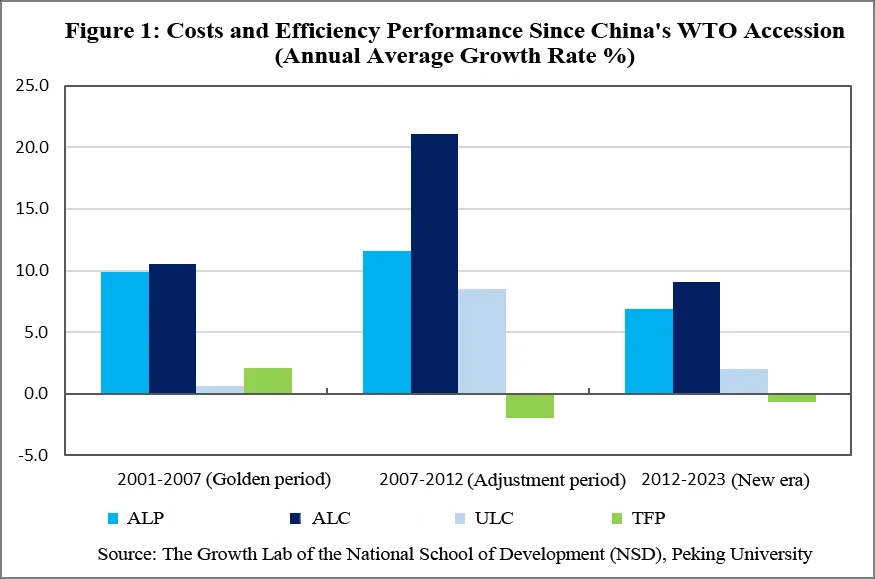

For comparison, Figure 1 divides China's economy since its accession to the WTO into three periods: the "Golden Period" (2001–2007), the "Adjustment Period" (2008–2012) amid the global financial crisis, and the "New Era" (2013–2023)—a provisional name for now. The "Golden Period" is recognised as the most favourable phase, not only because labour productivity grew at an impressive annual average rate of 9.9%, but also because this rate closely matched the annual average labour cost growth of 10.5%. Consequently, the ULC remained relatively stable, experiencing little to no significant increase.

However, during the "Adjustment Period," following the global financial crisis, labour cost growth accelerated dramatically by an annual average pace of 21.1%, nearly doubling the 11.6% growth rate of labour productivity. This discrepancy caused the ULC growth rate to surge to an average of 8.5% annually.

In the subsequent "New Era," GDP growth has faced mounting challenges. Both official estimates and re-estimations using theoretical models indicate that China's economic growth rate has declined from its previous peak, losing two-thirds of its earlier pace. This slowdown has significantly dampened growth in both labour productivity and labour costs, yet the increase in labour productivity still lags behind labour cost growth, reaching only 75% of the latter. This disparity continues to push ULC upward.

Superficially, addressing this issue might suggest solutions such as curbing the rise in labour costs, enhancing labour productivity, or tackling both concurrently. In practice, however, the problem is far more complex.

II. The Slowdown in labour Productivity is Essentially a TFP Problem

Theoretically, changes in labour productivity (𝑌/𝐿) can be broken down into two primary drivers: investment-induced capital deepening (𝐾/𝐿) and changes in total factor productivity (TFP). For labour productivity growth to have economic significance or to result from market competition, it must meet a critical condition: TFP cannot fall below zero. As the core measure of economic efficiency, TFP forms the basis for sustainable growth.

A widespread misconception that must be noted is equating overall labour productivity with efficiency, disregarding TFP performance. This misunderstanding stems from the Soviet-style planned economy, which operated without market constraints. Consequently, labour productivity has long been misinterpreted as an efficiency indicator in China's statistical system, a perspective that overlooks its true implications. Superficially, labour productivity seems simple: increased inputs yield higher outputs. For instance, equipping workers with more tools boosts their productivity.

However, in the absence of market benchmarks, a crucial issue arises—productivity gains from excessive investment often entail high costs and unaccounted efficiency losses. The inevitable outcomes are diminishing returns on capital, reduced fixed asset investment, capital withdrawal, and a sustained economic slowdown. Isn't this exactly the scenario China is facing today?

Let's take a look at the changes in China's TFP after joining the WTO. For comparison, the three periods previously mentioned will be used: the "Golden Period" following China's accession to the WTO, the "Adjustment Period" after the global financial crisis, and the subsequent "New Era."

The so-called "Golden Period" of the first stage is named as such due to its average annual TFP growth of 2.1%, while ULC remained largely stable. This is an impressive result, comparable to the TFP performance of post-war "East Asian miracles"! Although this estimate is based entirely on official data, it is derived from a theoretical framework that has been rigorously calculated to ensure full accounting for input costs.

Unfortunately, this "Golden Period" of China's economy was relatively short-lived. Following the transition to the "Adjustment Period," with ULC rising by 8.5% annually, TFP actually declined by 2.0% per year—a situation that is hard to accept both theoretically and empirically. In the subsequent decade-long "New Era," although the rate of TFP decline slowed, it remained within the negative growth range, marking a prolonged period of efficiency stagnation in the Chinese economy. The various challenges facing China's economy today are a direct consequence of the unsustainable burden of the country's prolonged low efficiency over the past fifteen years.

III. The Decline in TFP is Essentially an Institutional Problem

As a concept in accounting or measurement that captures gains achieved without direct costs, TFP has consistently been a crucial macroeconomic indicator, commanding primary attention in the analysis of economic growth drivers. TFP captures changes in an economy's efficiency by fully accounting for the costs of primary factors—namely, the costs of capital and labour borne by producers or users.

From the perspective of resource scarcity, the challenge of sustaining economic growth fundamentally revolves around efficiency. Specifically, it is a broad innovation challenge shaped by the imperative to enhance efficiency, encompassing both technological and institutional innovation. It is important to emphasise that this pressure does not originate from authority but from the innate human drive to freely pursue self-interest.

Consequently, the issue of TFP is essentially an institutional one—how to design an economic system that safeguards freedom and ensures fair competition through the rule of law. China's remarkable economic achievements since the reform and opening up can, to a significant extent, be attributed to institutional validation of market principles and the rejection of the planned economy system, though attributing this success solely to these factors would be an oversimplification.

Mainstream economics textbooks often interpret TFP solely as a measure of technological progress, implicitly making a significant institutional assumption: that the economy in question operates within a flawless institutional framework. This framework is presumed to eliminate all institutional barriers that could cause efficiency losses, such as restrictions on factor mobility, price distortions, structural imbalances, and weak incentives for innovation. Additionally, it assumes the economy can seamlessly adjust to accommodate technological innovations, including Schumpeterian "creative destruction," thereby fully realising expected efficiency gains.

In reality, even developed market economies fall short of meeting these idealised institutional assumptions. For developing economies, although imported technologies are generally low-cost to adopt, practical, and mature, their broader efficiency-enhancing effects can only be realized through comprehensive institutional reforms that adapt to these technologies. Such reforms must span various areas, including management practices, organisational structures, legal frameworks, policy measures, and political arrangements.

IV. The Challenge of Economic Transformation is Essentially a Challenge of Institutional Transformation

Given the institutional nature of TFP, it is evident that TFP growth is unlikely to be stable and may even decline at times, as institutional reforms inherently face resistance. This resistance stems from two primary sources. First, there is the conflict between new technologies and old institutions, where outdated technologies, traditional professions, entrenched bureaucratic systems, and their associated vested interest groups resist adopting new systems. Second, loopholes in newly implemented systems may create new vested interest groups. Both factors can lead to stagnation or even regression in institutional improvements.

The central challenge for China's economic transformation lies in whether new reforms can effectively address institutional deficiencies, reverse institutional regression, and overcome resistance to marketization. This perspective also helps resolve the theoretical dilemma of equating TFP with technological progress: Since technological regression is unlikely under normal circumstances, declines in TFP are often attributed to data inaccuracies or factors such as the endogeneity of the production function. However, it is now evident that assuming appropriate estimation methods (let's save this topic for a separate discussion), declines in TFP can only result from efficiency losses due to institutional regression. These declines represent the economic cost an economy bears due to such inefficiencies.

Examining Figure 2 and the aforementioned latest estimates—particularly the sustained decline in TFP that coincided with the rise in ULC, beginning during the "Adjustment Period" following the global financial crisis and continuing into the "New Era"—it is evident that the optimal window for China's economic transformation, namely the "Adjustment Period" from 2008 to 2012, was missed.

Why is this period regarded as optimal for transformation? Despite the unprecedented challenge of rising ULC during this time, TFP had not yet shown a significant decline. As Figure 2 indicates, the moderate decline in TFP commenced around 2009–2010, following the implementation of the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package. However, the most pronounced efficiency deterioration occurred during 2012–2014 and has since remained unrecovered. As a result, there has been no inherent momentum to improve labor productivity sufficiently to offset the rise in nominal labor costs.

So, was this "missed opportunity" due to mainstream economists and policymakers at the time overlooking critical cost and efficiency signals, or was it due to the inertia of the existing institutional framework, which prevented economic participants from effectively responding to the combined effects of rising costs and declining efficiency? At the very least, all policy efforts during the "New Era" failed to significantly improve TFP. This indicates that China's policies aimed at maintaining economic growth and increasingly interventionist industrial policies were, in most cases, misaligned with firms' efforts to enhance efficiency.

Undoubtedly, China faces no alternative but to confront the challenge of institutional transformation. This involves fully adopting a comprehensive market-based system safeguarded by the rule of law and genuinely integrating into, maintaining, and advancing a rules-based global market system. Without achieving this transformation, the Chinese economy risks prolonged low growth or even stagnation—an "equilibrium" commonly called the "middle-income trap."