Government grip on crop breeding threatens both yield and innovation: research

Stuck in inefficient government R&D & regulation, market-oriented reform is the most fertile ground for China’s next agricultural breakthrough, says a business-backed, non-govt thinktank on biotech.

Over the past decade, China has dramatically increased its focus on the seed industry, presenting it as a crucial pillar of food security for its 1.4 billion citizens. Despite multinational corporations accounting for just 3% of China’s seed market and imports making up only 0.1% of the total annual supply, according to the agricultural minister in 2021, the growing concerns over “seed security” have dominated state narratives in recent years.

According to Qiushi/Seek Truth, the flagship biweekly of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, China’s top leader issued directives on the subject of seeds nine times between late 2013 and mid-2022. One article in Outlook Weekly, a magazine under the state Xinhua News Agency, published in September 2020, highlighted:

Seeds are the cornerstone of modern agriculture. If there is excessive reliance on imports, a “seed shortage” could trigger a crisis even more severe than technological “chokepoint” issues.

Without high-quality seeds, not only food security cannot be guaranteed, but agricultural security could also be jeopardized.

With global seed industry innovations driven by biotechnology rapidly advancing, large foreign seed companies are restructuring and forming powerful alliances to seize global markets, posing a severe challenge to China’s domestic seed industry.

The proposed solution? Unsurprisingly, more government support for state-run institutions and increased protectionism against foreign imports and international collaboration, all in the name of safeguarding Chinese resources being appropriated and threatened by foreigners—classic, go-to strategies in an expanding security agenda.

However, a carefully researched report from the Huagu Institute recently presents a starkly different perspective: the government is not the solution; it is the problem.

The report, written by a Huagu team led by Hu Ruifa, a Peking University scholar, argues that the dominant role of government agencies, public agricultural research institutions, and state-run universities in crop breeding is undermining China’s food security strategy and its ambitions in agricultural biotechnology. It identifies a fundamental disconnect between bureaucratic limitations and market forces as the core issue. Despite inherent shortcomings, public institutions remain deeply involved in commercial breeding and crowd out private enterprises. This stifles private sector participation and innovation.

Startlingly, 79% of China’s nearly 9,000 seed companies invest less than $69,500 annually in R&D, with 44% reporting zero R&D spending at all. Meanwhile, the sprawling regulatory system is ineffective—an oversaturation of crop varieties has overwhelmed local regulators and fueled the proliferation of counterfeit products. The absence of exit mechanisms allows underperforming companies to persist, further hindering the growth of more innovative firms.

In contrast, multinational giants like Bayer and Corteva boast fully integrated R&D pipelines that combine biotechnology, data analytics, and large-scale testing. Yet, their access to China’s market remains heavily restricted. China’s own efforts to modernize, including the high-profile acquisition of Syngenta, have so far failed to yield the anticipated breakthroughs.

The report remarks that urgent reform is essential. To address this failure, the government must step back from commercial breeding and create space for market-driven innovation, a 2011 attempt that the report has boldly described as a failure.

"The most urgent priority is accelerating the withdrawal of government agencies from commercial breeding. This has become one of the most significant obstacles hindering the development of China’s seed industry. Only by resolutely taking this step can the sector truly embrace a brighter future,” it concludes.

Huagu Institute, short for Huagu Zhiyuan Biotech & Industry Institute 华谷致远生物科技与产业研究院, was founded by BGI Group, Cathay Biotech, Country Garden Agriculture, Beidahuang Group, and BGI Co-win. The Institute’s President, 梅永红 Mei Yonghong, is Director and Executive Vice President of BGI Group, one of the world’s leading life science and genomics companies.

Immediately before joining BGI, Mei was Mayor of Jining, Shandong Province, between 2010 and 2015. Before that, he served as Deputy Director-General of the General Office, Director-General of the Research Office, and Director-General of the Policy, Regulation, and System Reform Department of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST).

P.S. I am reminded—perhaps somewhat tangentially, and I hope you’ll forgive the comparison—of a passage from the Discourses on Salt and Iron 盐铁论, a record of the famous debate held at the imperial court in 81 BC. The debate featured rising Confucian scholars from across the country opposing government officials representing the established bureaucracy. In this excerpt, they argue over whether the state should provide materials for agricultural production, such as iron tools, grain, and farming techniques, or whether these should be left to the farmers themselves, while liberalising the role of the market.

Government officials said:

…officials proposed nationalising salt and iron production, unifying their usage and standardising prices, to benefit both the public and the state. Even the sage rulers Yu and Shun could not improve upon this method. If the bureaucrats explain the smelting methods clearly and artisans apply themselves earnestly, then the balance of hardness and softness will be achieved, and the tools will be both effective and easy to use. In such a case, what hardships would the people still suffer? What complaints would the farmers still have?”

Confucian scholars replied:

Those labourers and craftsmen again! In the past, when people were allowed to privately brew wine, forge iron, and boil salt, salt as well as grains were traded, and tools were well-made, affordable, and fit for use. Now the government manufactures tools that are mostly poor in quality, costly to make, and fail to reduce expenses…

When families privately produce ironware, fathers and sons work together in earnest. Only well-made tools are brought to market; substandard ones are not sold. During the busy farming season, carts distribute the tools across the fields and roads. People gather to purchase them, trading goods, grain, or even exchanging old tools for new ones. Sometimes, tools could be bought on credit, allowing work to proceed without delay…

But now, with everything monopolised under government control and prices fixed, tools are often too hard and poorly made, with no room for choice between good and bad. Officials in charge of sales are often absent, making it difficult to obtain tools…When iron tools produced by the government cannot be sold, they are sometimes unfairly distributed...

—Yuxuan Jia & Zichen Wang

The East is Read featured a speech by Mei Yonhong last December. The following report remains available on Huagu Institute’s official WeChat blog.

中国种子产业现状、问题及对策——华谷研究报告

China’s Seed Industry: Current Status, Challenges, and Reform Pathways — A Huagu Research Report

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, particularly after reform and opening up, China’s seed industry has made significant progress. Through its own efforts, China has managed to feed one-fifth of the world’s population, achieving remarkable accomplishments. These achievements have been made possible by advancements in technology, effective management measures, and, most importantly, the hard work of countless agricultural workers. However, the development of China’s seed industry has not been without setbacks, and it currently faces several pressing challenges.

I. Current Status of China’s Seed Industry — Rapid Changes in the Per-Unit Yield Levels of Three Major Grains

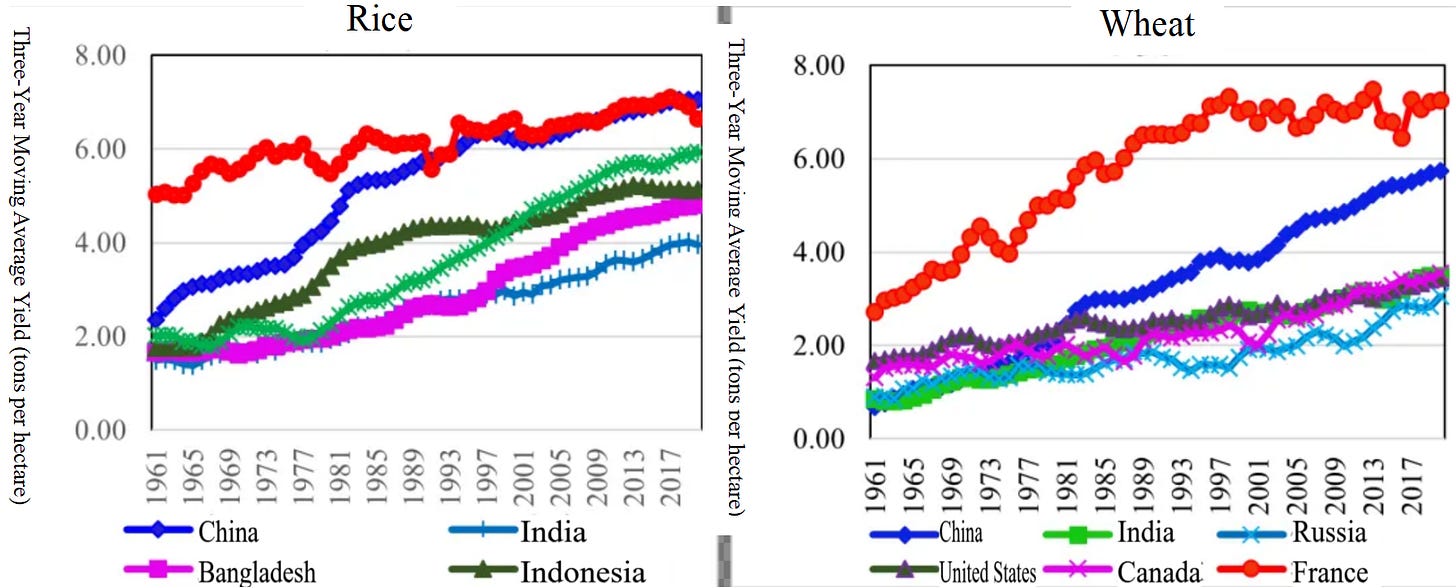

The development of the seed industry is most evident in the rapid changes in the per-unit yield levels of China’s three major grains. Specifically, the yield levels of rice and wheat have reached international standards, while maize yields still lag significantly behind those of developed countries.

(1) Noticeable Progress in Rice Yield

In the early 1960s, China’s rice yield levels were far below Japan’s but above those of developing countries such as India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. From 1961 to 1963, China’s average rice yield per hectare was only 2.35 tons, less than half of Japan’s 5.03 tons. However, it was 41.0% higher than Indonesia’s 1.67 tons per hectare, and 57.1% higher than India’s 1.50 tons. Even by the early years of reform and opening from 1978 to 1980, China’s yield remained well below Japan’s 1961 level, reflecting a gap of more than two decades.

After reform and opening up, by 1991-1993, China caught up with Japan and was progressing in step with it, further widening the gap between itself and countries such as Indonesia and India. It is worth noting that although Japan ranks among the world’s leaders in rice yields, substantial government subsidies have kept production costs exceptionally high, rendering its rice uncompetitive in the marketplace.

(2) Wheat Yield Level Growing the Fastest

In the early 1960s, China’s wheat yield was not only significantly lower than that of developed countries such as the United States and Canada, but also lagged behind developing countries like the Soviet Union and India. Following reform and opening up, by 1978–1980, China’s yield had risen to 1.96 tons per hectare, surpassing that of Canada, India, and the Soviet Union, and reaching 88% of the U.S. level (2.22 tons per hectare). However, it still fell short of the U.S. level from 1968–1970 (2.02 tons per hectare), indicating a time lag of over a decade.

By 1983–1985, China’s yield had climbed to 2.74 tons per hectare, exceeding the contemporary U.S. level of 2.55 tons per hectare and far outpacing Canada, the Soviet Union, and India. By 2018–2020, the yield further increased to 5.60 tons per hectare, 68% higher than the U.S. yield of 3.34 tons per hectare (see Figure 1). Notably, compared with France—where wheat is typically grown once a year—the yield gap between China’s double-cropping system and France’s narrowed significantly, with China’s yield increasing from 60.8% below France’s level in 1978–1980 to just 21% below in 2018–2020, as the absolute difference shrank from 3.04 to 1.47 tons per hectare.

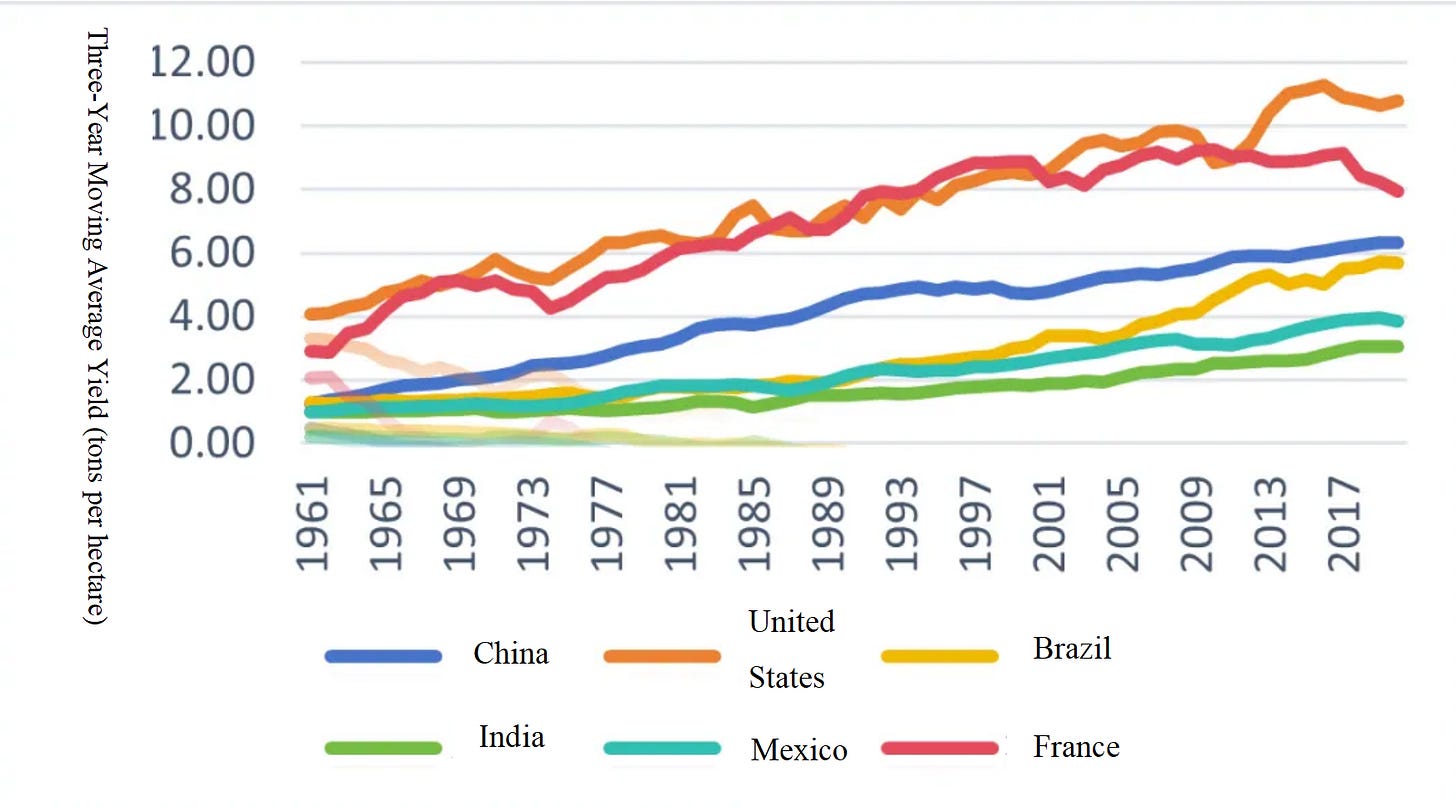

The yield gap in maize is widening. Unlike rice and wheat, China’s maize yield has not narrowed the gap with the United States since reform and opening up; on the contrary, it has continued to widen (see Figure 2). In the early 1960s, China’s maize yield lagged significantly behind that of countries such as the United States and France. Between 1987 and 1989, China’s yield averaged 3.91 tons per hectare—still below the U.S. level from 1961–1963 (4.08 tons per hectare), reflecting a lag of 26 years. By 2018–2020, China’s yield had reached 6.25 tons per hectare, yet remained behind the U.S. level from 1977–1979 (6.31 tons per hectare), widening the gap to 41 years.

Notably, since the mid-1990s, U.S. maize yields have also pulled away from those of France, another developed country. From 2000–2002, the U.S. yield was on average 0.41 tons per hectare lower than France’s, but by 2018–2020, it had surpassed France’s by 2.34 tons per hectare. Meanwhile, Brazil, a developing country, raised its maize yield from 50% of China’s level during the early reform period (1978–1980, at 1.48 tons per hectare) to 88% of China’s level by 2018–2020 (5.53 tons per hectare).

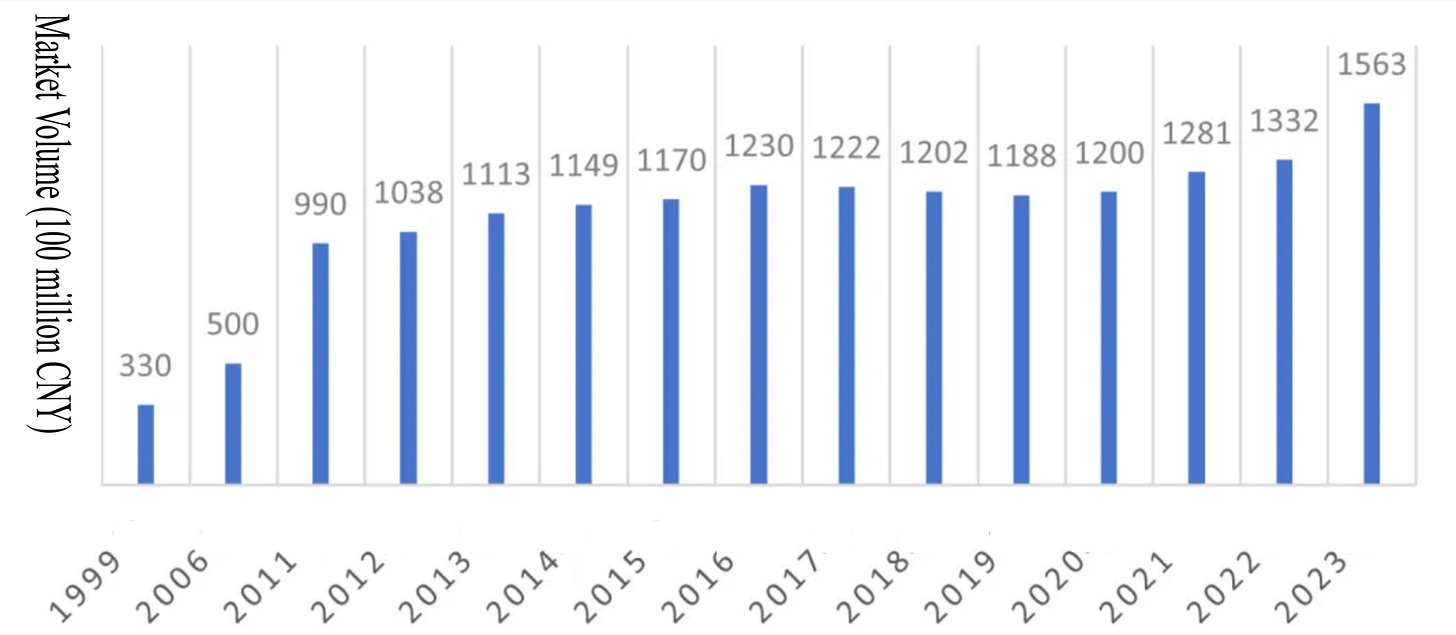

II. Prominent Issues in China’s Seed Industry

According to data from the global agricultural market research firm Kynetec, the global seed industry expanded from $43.2 billion in 2016 to $52 billion in 2021, with a compound annual growth rate of 3.8%. As the world’s largest agricultural producer, China is also one of the top consumers of seeds. In 2023, China’s seed market reached 156.3 billion yuan, accounting for approximately 42.6% of the global total ($52.06 billion), making it the largest seed market in the world (see Figure 3). While this represents remarkable progress, a number of serious challenges remain, primarily reflected in the following areas:

(1)Small and Weak Seed Companies

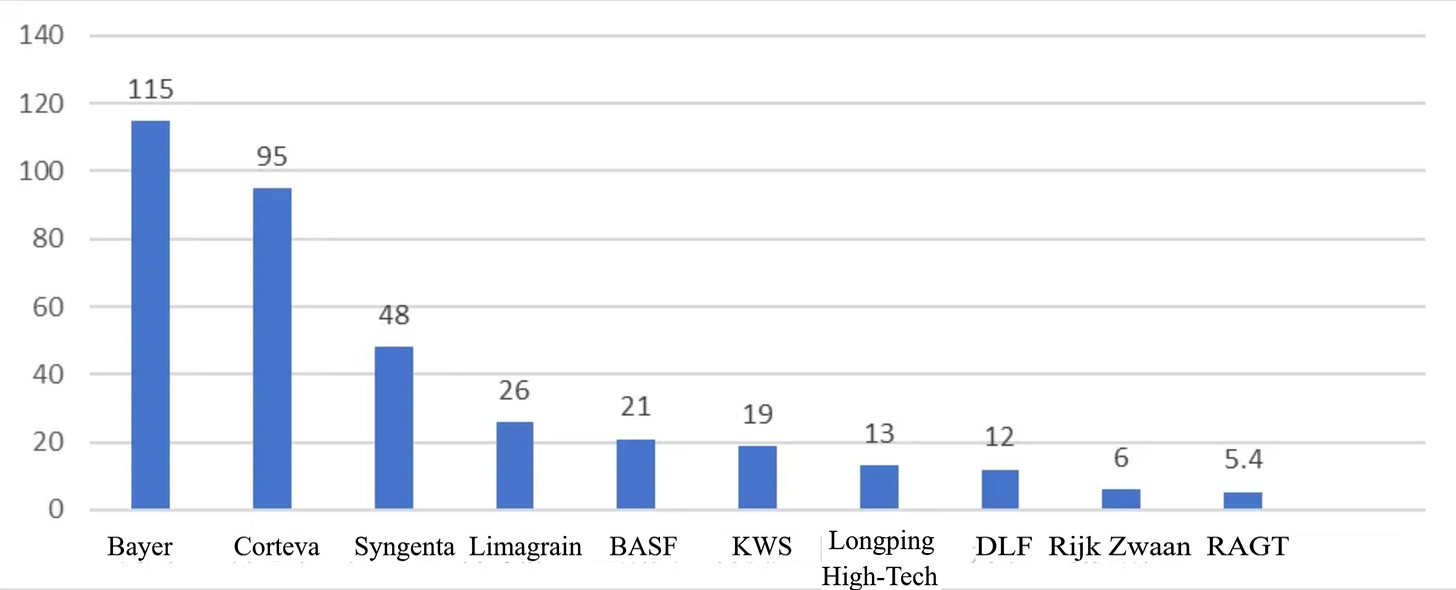

The global seed industry is trending toward diversification, conglomeration, and internationalisation. Multinational seed corporations are expanding through mergers and acquisitions, resulting in greater industry concentration, increased scale, and deeper integration across the seed industry value chain. Globally, the top 20 seed companies exhibit a pattern described as “two giants and four strong contenders with divergent trajectories.” Bayer and Corteva, the two dominant players, account for 58.26% of total sales among the global top ten. They are followed by Syngenta, Limagrain, BASF, and KWS, which together contribute 31.63% of sales (see Figure 4).

In 2023, there were 9,841 licensed seed companies in China, with 8,721 actively engaged in production and operations. However, few of these companies have substantial market influence. The largest seed company in China by annual sales is Longping High-Tech, with sales of approximately $1.3 billion, ranking seventh globally. This is only 11.30% and 13.68% of the annual sales of the top two companies, Bayer ($11.5 billion) and Corteva ($9.5 billion), respectively.

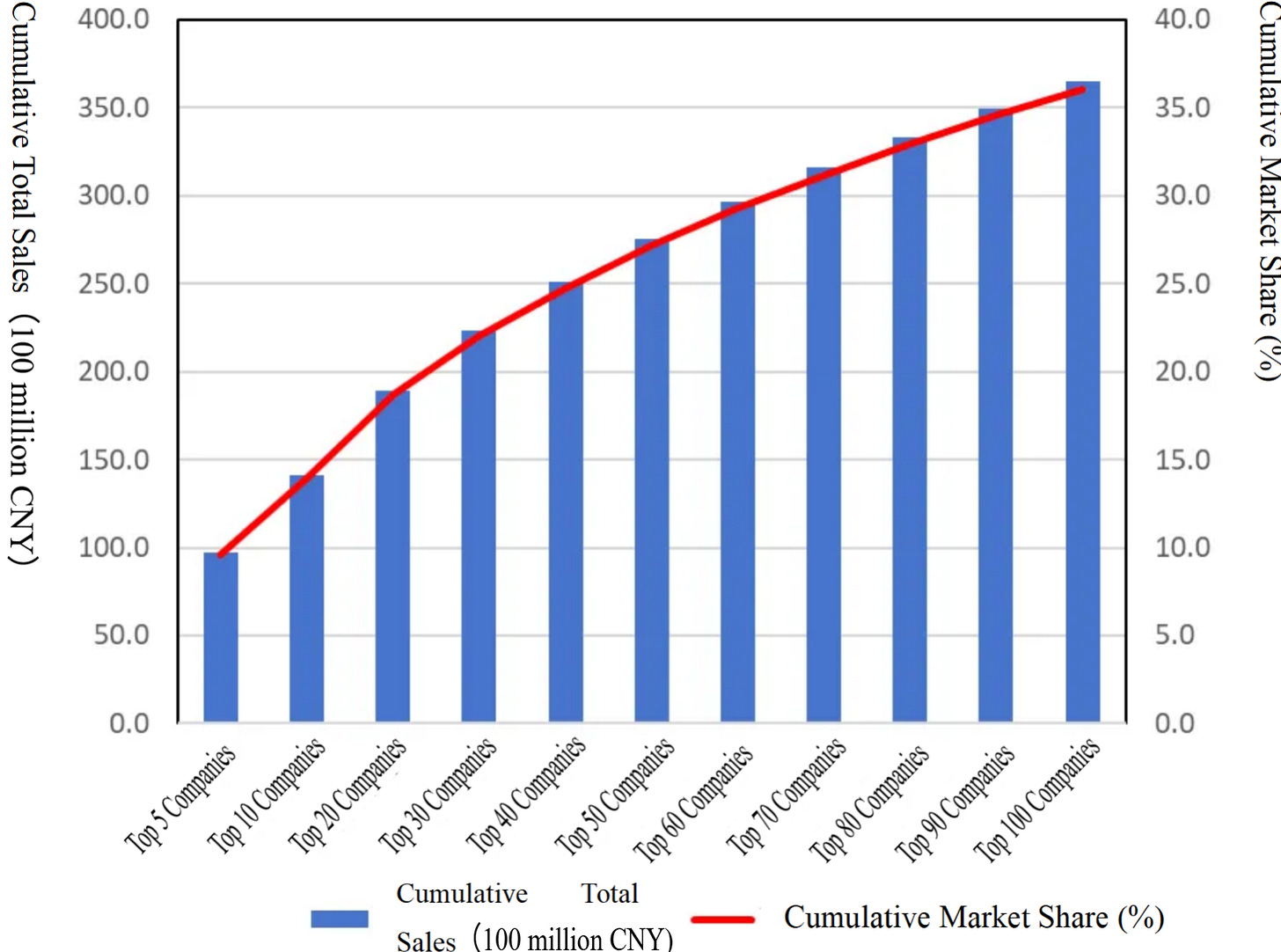

The combined sales of China’s top five seed companies total 9.74 billion yuan, accounting for just 7.31% of the national market. The top 100 Chinese companies collectively generate 36.47 billion yuan in sales, representing 27.38% of the national market share. A total of 4,384 and 3,454 seed companies have annual sales below 2 million yuan and 1 million yuan, respectively, comprising 53.7% and 42.3% of all seed enterprises in China (see Figure 5).

(2)Low and Fragmented R&D Investment

Chinese seed companies invest very little in research and development. In 2023, the total R&D expenditure by all seed companies in China amounted to 7.6 billion yuan, which is less than 69% of Bayer’s seed R&D expenditure, which stands at 11 billion yuan1. Even Longping High-Tech, the company with the highest R&D investment in China, spent only 817 million yuan on R&D in 2023.

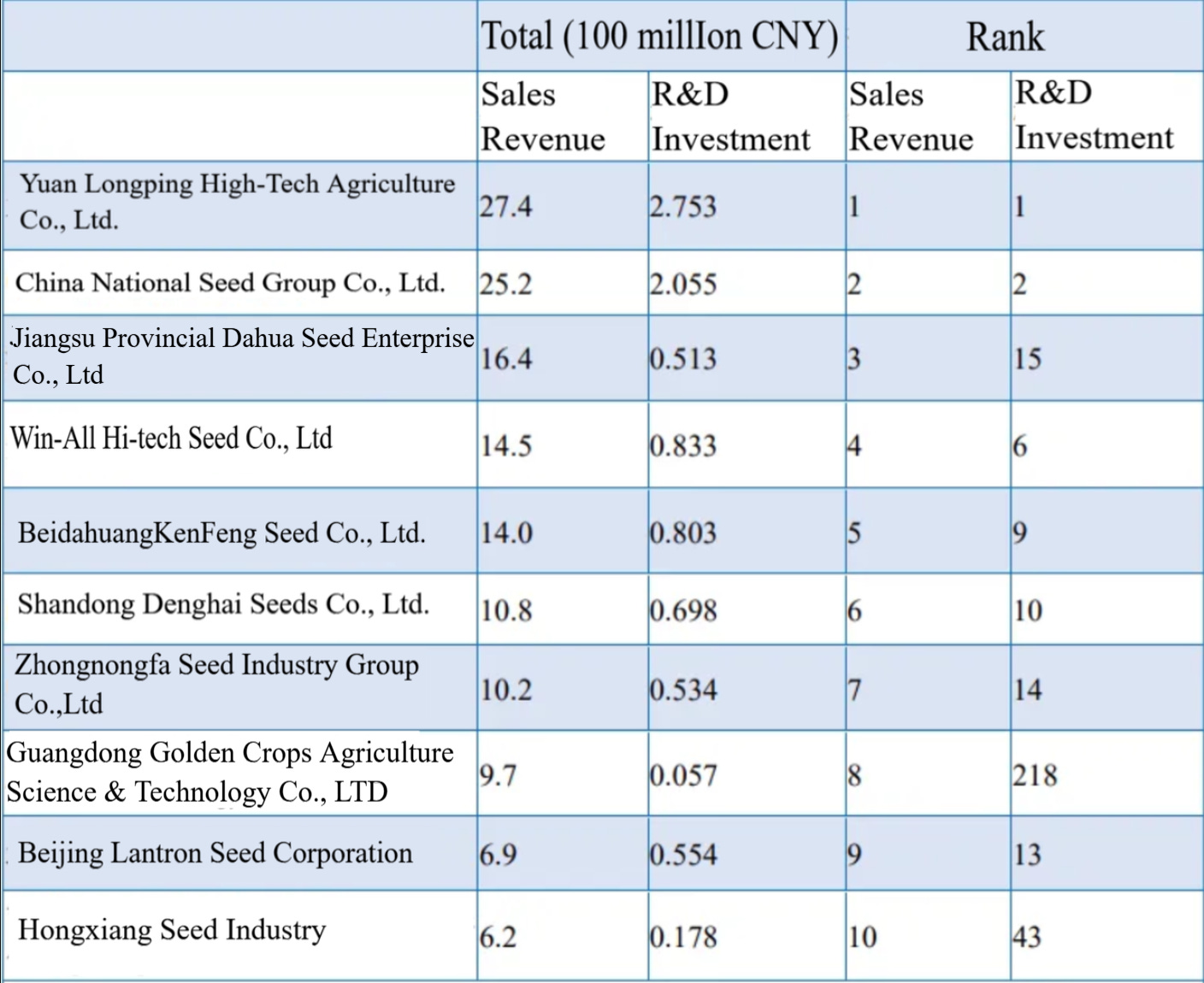

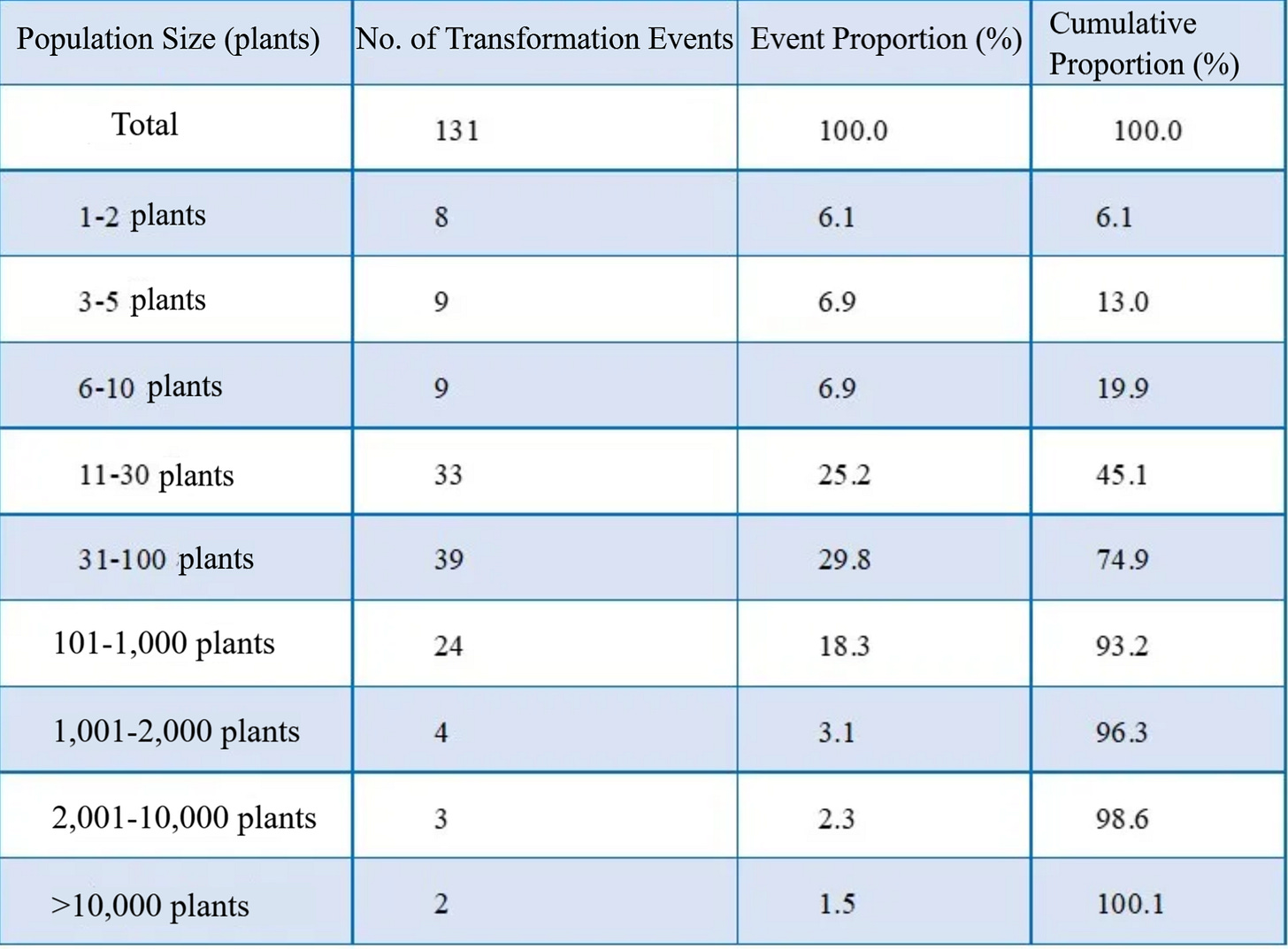

Moreover, there is a mismatch between R&D investment and market share among Chinese companies. In 2023, out of 8,721 seed companies in China, 6,893 had annual R&D investments of less than 500,000 yuan, representing 79% of the total. Alarmingly, 3,876 companies (44%) had no R&D investment at all. Although the top five companies accounted for 11.0% of the total R&D investment among all companies, this did not correspond to their seed sales. For example, among the five largest seed companies by sales, only two ranked in the top five for R&D investment. The other three companies’ R&D investments ranged between just 18.6% and 30.3% of that of the highest R&D spender (Table 1). This indicates that a significant portion of seed companies do not prioritise R&D as a key element of their development strategy.

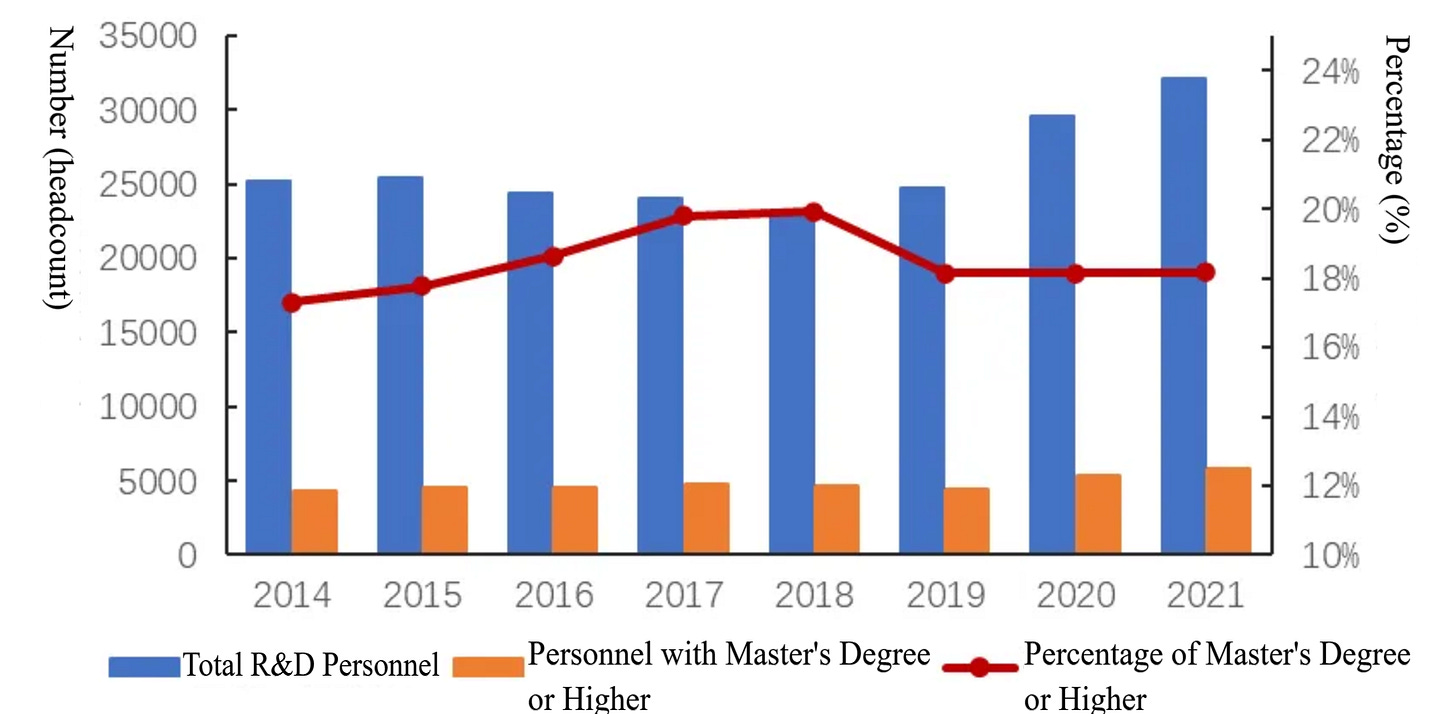

In addition to low levels of R&D investment, there is insufficient attraction and cultivation of breeding talent in China’s seed industry. For example, the proportion of employees with a master’s degree or higher in registered seed companies nationwide has shown minimal growth, rising only from 17.3% in 2014 to 18.2% by 2022 (see Figure 6). This talent gap undermines the industry’s capacity to leverage advances in molecular breeding.

China’s seed industry is currently structured around three major state-owned systems: Syngenta, under Sinochem Holdings; Longping High-Tech, whose largest shareholder—CITIC Agriculture—is under the Ministry of Finance; and SDIC Seed, a wholly owned subsidiary of the State Development and Investment Group Co., Ltd. (SDIC Group). In addition to these three state-owned giants, several enterprises specialising in plant trait development—including DBN Group, RFGene, Longping Biotech, and KingAgroot—are also noteworthy. Since 2017, KingAgroot has invested 2 billion yuan in biological breeding, positioning itself as the most likely Chinese firm to achieve original innovation in herbicide-resistant crops. Most other private companies, however, have made only limited investments in biological breeding research, constraining their ability to develop internationally competitive products.

(3)Broad and Disordered Approval and Regulation of Seeds

The Chinese government has established a large-scale seed regulatory system from the top down. Under this framework, the government oversees the approval of crop varieties and the quality of seeds in the market. Consequently, seed companies are not held accountable for yield losses incurred by farmers due to poor varietal performance. This transfer of responsibility from enterprises to regulatory authorities has encouraged the entry of underqualified firms into the seed market (see Figure 7).

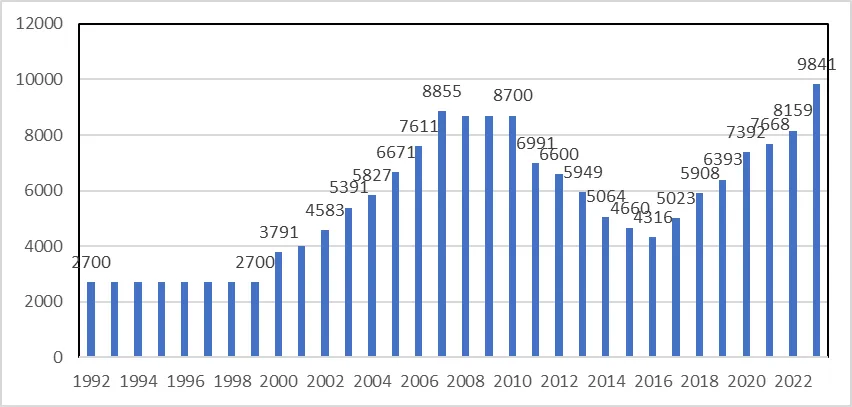

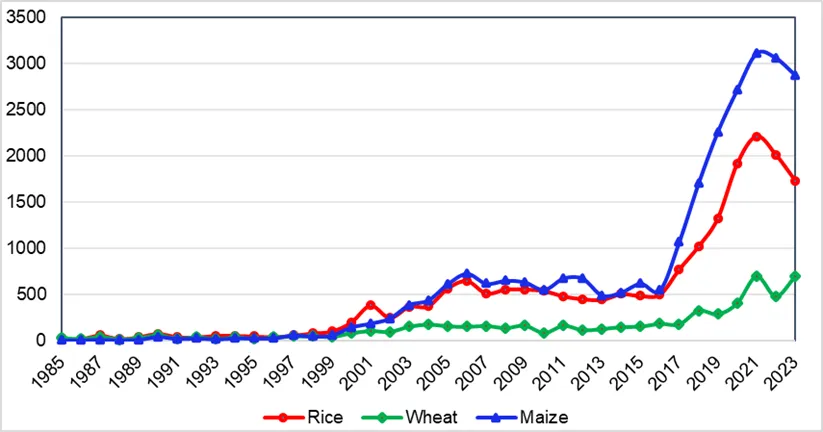

In the context of heavy-handed government oversight, China implements a major crop variety approval system. This system requires that seeds for major crops sold in the market must be approved by provincial or higher-level government authorities. Prior to the issuance of the first Seed Law in 2000, major rice-, maize-, and wheat-producing provinces approved an average of only 2 to 3 new varieties per year. Following the introduction of the law, the number of hybrid rice and maize varieties that are more readily protected by intellectual property rights increased rapidly as companies sought greater market share. By 2010, the number of approved varieties had risen to 550 for rice and 650 for maize.

The rapid proliferation of varieties placed a heavy financial burden on the institutions responsible for conducting regional variety trials—namely, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and provincial agricultural departments—and created significant regulatory challenges. In response, the number of approved rice and maize varieties was reduced to 486 and 622, respectively, by 2015. However, the numbers rebounded quickly, reaching 2,011 for rice and 3,061 for maize by 2022 (see Figure 8).

The overwhelming number of approved varieties presents a major enforcement challenge for seed regulatory authorities. This issue is compounded by the limited enforcement capacity of local governments, particularly at the county level and below, resulting in the widespread circulation of counterfeit seeds in the market.

(4) Outdated and Lagging Research Models

Multinational corporations have adopted molecular breeding technologies for commercial breeding programs. First, they have established R&D pipelines designed according to the most globally advanced technological frameworks. These pipelines follow the full process of molecular breeding, with each stage structured and managed in alignment with the company’s production model.

Second, to maximise profits, these corporations apply cutting-edge technologies to molecular breeding R&D. These include molecular design, marker-assisted selection, genetic transformation, gene editing, biosynthesis, and other molecular biology technologies.

Third, they manage their R&D processes using a model-based, assembly-line approach. The entire breeding R&D process is divided into two main phases: the laboratory phase and the field phase. The laboratory phase involves the use of biotechnology techniques for activities such as genome sequencing of parental lines, parental selection and DNA cloning, as well as genetic transformation and gene editing. The field phase includes backcrossing and trait introgression, hybridisation and progeny selection, as well as trials for new lines and variety evaluation. All stages of the R&D process are managed by pre-established standards and managed through a model-based R&D framework.

Unlike multinational corporations, the vast majority of China’s breeding research institutions and enterprises still operate under a project-based R&D model, relying on traditional crossbreeding techniques. Research activities depend primarily on the experience of individual breeders, who select parents for hybridisation based on long-term observation and familiarity with plant genetic resources. Subsequent steps—such as progeny selection and the development of new lines and varieties—are carried out manually by project teams.

For breeding research involving modern biotechnologies such as genetic transformation and gene editing, the work is not only handled by separate project teams but is also fragmented across them. For example, in transgenic breeding, researchers focused on upstream gene cloning are often reluctant to share high-value gene constructs with mid- and downstream teams.

Meanwhile, midstream groups studying genetic transformation frequently omit a critical step: transformant screening. Once a cloned gene has been transformed, any offspring that express the gene are treated as new transformants and directly used in downstream breeding research. This stands in sharp contrast to the practices of multinational corporations, which generate thousands of transgenic offspring for each gene transformant. Then, through rigorous selection from these expression populations, they identify and advance the most competitive transformants for downstream variety development.

The current system significantly undermines the competitiveness of China’s crop varieties (see Table 2).

(5) Wasteful and Disordered Utilisation of Plant Genetic Resources

A noteworthy concern is that Chinese breeding institutions have not applied the precise identification and utilisation of plant genetic resources to breeding R&D. First, progress in the precise identification of preserved genetic resources has been slow. Although China holds the world’s second-largest collection of plant genetic resources, totalling 539,100 accessions, fewer than 15,000 have been thoroughly characterised. The identification and utilisation of elite traits and resistance genes still fall short of meeting breeding demands. In contrast to multinational corporations, which have fully sequenced and systematically profiled their plant collections, China has yet to complete comprehensive studies of its resources.

Second, even where sequencing has been conducted, the resulting data are not accessible to all breeders, limiting effective utilisation. And when genetic information is available, breeders still face practical barriers in integrating it into applied breeding programs.

A recent survey of eight leading Chinese seed companies revealed that most rely on in-house plant resources accumulated over the years or on widely cultivated commercial varieties for their R&D activities, with limited incorporation of foreign-introduced resources. Utilisation of these materials is largely based on breeders’ observations, with little supporting data on performance across diverse environments or molecular-level genetic profiles. Access to government-preserved plant genetic resources remains constrained, and their practical integration into breeding programs is uncommon.

These problems arise in part from neglect, in part from mismanagement, but more fundamentally from poorly designed and inefficient institutions.

III. Current Status and Challenges of China’s Seed System

The changes in per-unit yield of the three major staple crops (rice, wheat, and maize) reflect the actual progress of agricultural science and technology in China, as well as the realities of the existing scientific institutions and policies.

(1) Current Status of China’s Seed System

The seed system comprises three components: the R&D system, the market system, and the regulatory system. Among these, R&D lies at the core, as it determines both the technological sophistication and innovation potential of seed development. The market system shapes the degree of market openness and the characteristics of market participants, particularly seed sellers (i.e., seed companies). The regulatory system encompasses the laws, regulations, policies, and institutional frameworks established by the government to maintain market order and ensure the security of seed supply. The specifics are as follows:

1. R&D System

Globally, there are two principal R&D models: government-led and enterprise-led systems. In most countries, public research institutions focus primarily on developing conventional crop varieties for which intellectual property protection is difficult. Government subsidies typically support these efforts. Private companies concentrate on hybrid varieties, which offer stronger intellectual property protection, as well as on conventional crops where cost recovery is still feasible, even when farmers retain seeds for reuse.

The government-led R&D system is structured around research projects and is primarily engaged in breeding new crop varieties with weak intellectual property protection. However, this model faces significant constraints in both personnel and resources. On the one hand, limited research staffing sharply reduces the number of hybrid combinations and progeny that can be generated. On the other hand, as institutions tasked with public research mandates, their experimental fields and equipment are often limited in scale, and efforts to expand field capacity or upgrade facilities are hindered by administrative restrictions and funding limitations.

In contrast, the enterprise-led R&D model operates through structured pipelines, placing strong emphasis on efficiency and market competitiveness. When developing new varieties, companies focus on whether the technology ensures effective intellectual property protection and whether R&D costs can be recovered.

Multinational corporations have advanced this model further, achieving industrialised and specialised R&D operations. Their breeding process is divided into distinct stages, including genetic material collection, gene sequencing, parent selection, field hybridisation, progeny selection, and the evaluation and promotion of new lines. Each stage is arranged in a production-line layout, with R&D progressing step by step through the pipeline until commercially competitive varieties are developed and promoted for adoption by farmers.

In order to cultivate crop varieties that are significantly superior to existing ones, businesses have raised funds to establish internationally leading R&D teams and laboratories. These facilities operate with a production-oriented approach, and their testing throughput, operational efficiency, experimental field area, and the scale of hybrid progeny populations are several times—or even hundreds of times—greater than those of government research institutions.

China’s seed R&D system is primarily government-led. Government research institutions are responsible for breeding both conventional varieties, for which intellectual property protection is relatively difficult, and hybrid varieties, for which intellectual property protection is comparatively easier. At the same time, the government provides its affiliated units, including relevant departments in higher education institutions, with funding for daily operations, infrastructure construction, and equipment upgrades, as well as research grants to support the development of new varieties.

2. The Market System

The seed market landscape largely depends on the degree of market openness and the characteristics of participating seed companies. Internationally, most countries maintain open seed markets dominated by multinational corporations. Within this framework, multinationals typically conduct foundational research in new variety development, including biological, biotechnological, and basic applied research, in the country where their headquarters are located. Simultaneously, they establish R&D subsidiaries, variety testing stations, and seed distribution networks across the globe. Through a coordinated division of labor between central R&D centers and regional branches, these corporations are able to develop crop varieties tailored to diverse local environmental conditions worldwide.

Whether a country’s seed market is dominated by multinational corporations depends on the degree of market openness, which in turn influences the overall development of its seed industry. In some smaller countries, limited domestic R&D capacity means that agricultural production relies heavily on technical support from multinational corporations, making market liberalisation an inevitable choice.

By contrast, countries such as Japan, Australia, and several developed European nations possess the scientific and financial resources to develop new crop varieties. However, due to the relatively small size of their domestic markets, the development of their seed industries remains uneven. For example, while the seed sector for certain crops may be well developed, seeds for major staple crops still depend on supplies from multinational companies.

As with other product markets, seed markets in these countries are open, forming a shared market space among Western nations.

China’s seed market, on the other hand, is not open. The breeding of major grain and cash crop varieties, as well as seed sales, is primarily carried out by domestic institutions. China enforces a “negative list” system in modern biotechnology and new variety development, which prohibits foreign companies from conducting related research or commercial activities in the Chinese market. Although multinational corporations such as Corteva, Bayer, and CP Group have established experimental stations in China and developed certain varieties, their R&D activities have been tightly restricted over the past decade.

In recent years, the Chinese government has sought to modernise the seed industry through acquisitions of multinational firms such as Syngenta. However, this strategy has not yielded the anticipated progress in the broader development of China’s seed sector.

3. The Regulatory System

The regulatory system of the seed industry refers to a series of institutional arrangements formulated by the government to maintain market order and ensure seed supply security. It includes laws and regulations, market governance and organisations, as well as supporting policies.

The regulatory system consists of government regulation and enterprise self-discipline.

Government regulation refers to the establishment of seed regulatory agencies responsible for overseeing the market entry of seed enterprises and supervising their operations. Enterprise self-regulation means that companies must register with the industrial and commercial administrative authorities upon entering the seed market. In cases where companies violate market order or relevant laws and regulations, such matters are addressed through the judicial system.

When the seed market is not yet mature or national food security cannot be guaranteed, many countries choose the model of government regulation. For example, in populous countries such as China and India, food security is not only a matter of national security but also impacts international markets. Therefore, maintaining order in the seed market has become one of the most important agricultural policies in these countries.

In contrast, most developed and developing countries internationally adopt the model of enterprise self-regulation. In countries with mature seed industries, the market is often dominated by a few multinational corporations or large enterprises. Seed sales are typically handled by their subsidiaries or contracted agents, and the crop seeds available on the market are largely developed by these companies, resulting in relatively uniform varieties and quality. Given this market landscape, enterprise self-regulation has become the primary mode of seed market governance in these countries.

It is understandable that countries have adopted different governance models based on their unique historical circumstances. However, as economies and societies evolve and global trends advance, governance structures must also adapt to meet the needs of the times. China is a typical example of a country that governs its seed market through government regulation, supported by a large and well-established seed regulatory apparatus.

At the national level, the Department of Seed Industry under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China is responsible for formulating strategic policies for seed industry development. The National Agro-Tech Extension and Service Centre hosts several public institutions tasked with seed regulatory functions, including regional trials for new crop varieties, variety approval, and seed market oversight.

In parallel, provincial agricultural departments have established provincial departments of the seed industry, which are responsible for variety advancement, market supervision, regional trials, and variety approval within their jurisdictions.

Below the provincial level, prefectural (municipal), county, and township governments have also set up their own seed regulatory bodies. Among these, institutions at the county and township levels focus primarily on law enforcement, ensuring that farmers plant high-quality varieties best suited to local conditions and capable of delivering maximum yields.

This multi-level regulatory system reflects China’s strong emphasis on and strict control over food security and seed market order. However, it has also led to substantial waste of human and financial resources, and has caused China’s seed R&D to lag behind internationally. For example, the yield gap in maize per hectare between China and the United States has widened from 26 years to 41 years. This divergence is partly attributable to the commercialisation of genetically modified crops in the United States since the 1990s, as well as structural deficiencies in China’s seed industry R&D system.

(2) Current Institutional Challenges in China’s Seed Industry

1. Participation of Government Research Institutions in Commercial Breeding

This is the most significant issue and the root cause of many problems. Currently, government agencies remain directly involved in commercial breeding within China’s seed industry. Agricultural research institutions above the prefectural level, along with agricultural universities, continue to treat commercial breeding as a core activity. However, such breeding is typically conducted by small research teams on a project basis with limited personnel and experimental resources, leading to crop varieties that are not sufficiently competitive.

In this context, government research institutions benefit financially by selling the varieties they develop. At the same time, because these breeding efforts are supported by public funds, the cost for enterprises to purchase new varieties is significantly lower than the cost of independent development, which weakens innovation incentives for the enterprises.

2. Unregulated Competition Among Small Enterprises Disrupts the Market

The proliferation of seed varieties and the practice of small companies purchasing government-developed varieties and marketing them under their own labels have become major contributors to disorder in the seed market.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the number of rice and maize varieties registered at the provincial level or above by companies surpassed those registered by government research institutions in 2011 and 2004, respectively. However, our analysis of all developed varieties shows that in 2019, 58.0% were either purchased from or jointly bred with government entities, outnumbering those independently developed by companies. Although the number of corporate in-house varieties later exceeded purchased and collaborative ones, the proportion remained as high as 48% in 2022. Moreover, some small firms take advantage of low-cost, lower-quality government-developed varieties, illegally marketing them under their own labels and seriously undermining the seed market.

3. Low-Threshold Approval System Fuels Proliferation and Disorder in Crop Varieties

China’s long-standing variety approval system and the large number of newly approved crop varieties have contributed to agricultural progress. However, the system’s weak selection criteria resulting from its low entry threshold have also resulted in an oversupply of disorganised and substandard varieties in the seed market.

Multinational corporations require a minimum yield advantage of 10% to select experimental entries for advancement. Only those that meet or exceed this threshold enter comparative trials, and among them, only the top-performing lines proceed to multi-location, multi-environment trials.

Most Chinese breeding institutions, however, allow lines that merely outperform control varieties to advance directly to provincial or national regional trials. Furthermore, a common practice among some seed companies and research institutions involves backcrossing established commercial varieties and rebranding them as “new varieties” for trial approval. These so-called breeding practices that infringe on intellectual property rights further contribute to market disorder.

4. Seed Business Licensing System Lacks an Effective Exit Mechanism

China currently enforces a seed production and operation licensing system, requiring enterprises engaged in the seed business of major crops to obtain a license issued by provincial or higher-level authorities. To qualify, companies must possess at least one approved self-developed variety, a registered variety for which they are the primary breeder, two jointly developed approved varieties, or three varieties with transferred breeding rights. However, the regulation does not specify a clear validity period for the varieties used to meet these licensing requirements.

Investigations reveal that among the over 3,000 approved maize varieties and 2,000-plus rice varieties each year, fewer than 10% achieve a cultivation area exceeding 100,000 mu [6,666.7 hectares]. The proliferation of these minor varieties severely disrupts seed market order, significantly hindering the growth of enterprises with high-performing varieties and ultimately undermining the whole industry’s development.

IV. The Most Pressing Priority

China’s earlier attempt to reform the seed industry—the “Seed Document No. 8” initiative, which aimed to withdraw public research institutions from commercial breeding and position enterprises as the primary drivers of seed R&D and industrialisation by the end of the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015)—failed, serving as a sobering lesson.

As the foregoing analysis makes clear, China’s seed industry still requires substantive reforms across multiple areas. These include raising approval standards for major crop varieties to weed out enterprises lacking genuine R&D and operational capabilities; establishing clear exit mechanisms for major crop varieties and seed business licenses; significantly strengthening law enforcement within the seed sector; and advancing a market governance model centred on enterprise self-regulation.

However, among all necessary reforms, the most urgent priority is accelerating the withdrawal of government agencies from commercial breeding. This has become one of the most significant obstacles hindering the development of China’s seed industry. Only by resolutely taking this step can the sector truly embrace a brighter future, which would yield positive outcomes in at least four aspects:

First, it will optimise resource allocation and enhance market efficiency.

Government involvement in commercial breeding tends to concentrate excessive resources in a select number of institutions while neglecting the role of market . Commercial breeding requires rapid responsiveness to market demands—a capability often constrained by institutional inefficiencies when government agencies are involved.

Second, it will clarify the boundary between government and market, fostering fair competition.

Government involvement in commercial breeding has disrupted market fairness. The involvement of state resources grants public research institutions preferential treatment in market access, funding, and favourable policies, placing private enterprises at an inherent disadvantage. This undermines equitable competition and inevitably leads to market disorder.

Third, it will stimulate corporate innovation and advance seed industry modernisation.

Enterprises are the primary drivers of technological innovation, and commercial breeding requires robust market incentives and innovative capabilities. The withdrawal of government agencies from commercial breeding will compel companies to increase R&D investments and establish a market-oriented breeding system.

Fourth, it will enhance the international competitiveness of China’s seed industry.

Amid increasingly fierce global competition in the seed sector, China’s seed enterprises must rely more on their own capabilities to participate in international market competition. The withdrawal of government agencies from commercial breeding will drive companies to establish global R&D and market systems, thereby strengthening the international competitiveness of China’s seed industry.

The development of China’s seed industry remains a long and challenging journey, making reform not only necessary but urgent. Only by deepening reforms in line with the sector’s underlying economic principles, and by fully acknowledging both the institutional resistance from public R&D entities and the inherent difficulty of reform, can the true significance of accelerating the government’s withdrawal from commercial breeding be understood. This shift is essential for achieving high-quality development in China’s seed industry.

According to 2023 data, Bayer Crop Science invested approximately €2.4 billion in R&D. Seed-related R&D accounted for about 60%~70% of this expenditure. Using the lower bound of 60% and the 2023 average exchange rate (€1 ≈ RMB 7.64), the calculation yields 24×7.64×60% = 11 billion yuan.

Seeds are not an industry and making China reliant on GMO foods or one use seeds made by multinationals would be a terrible mistake. I do not see a discussion about the real dangers of GMOs and their use by multinationals to create dangerous dependency anywhere here.

Food sovereignty is not a bad thing, but in particular keeping bad actors like Bayer/Monsanto out of one's food system is to be commended. The problem with governments is they love power, the problem with corporations is they love the power to profit, particularly monopoly, even if that requires destroying the ecology that sustains life.