Dragon or loong: much ado about nothing

The name boondoggle with Chinese cultural representation

The Chinese dragon (龙/龍), originally a symbol of imperial power and later the embodiment of the Chinese nation-state, is also a point of contention for some. Opponents of the translation "dragon" argue that because the Chinese traditional beast shares a name with the felonious monster in Western culture, it carries built-in associations with evil. They believe that as China engages more with the world, this association will damage China's global interactions and image. This debate, dating back to 2006, has resurfaced with the advent of 2024, the Year of the Dragon.

However, as the author of the following article said, "When viewed as alien, no matter how pleasant your name is, you will be depicted negatively. When seen as a friend, even a name like 'mouse' can be endearing, as in Mickey Mouse."

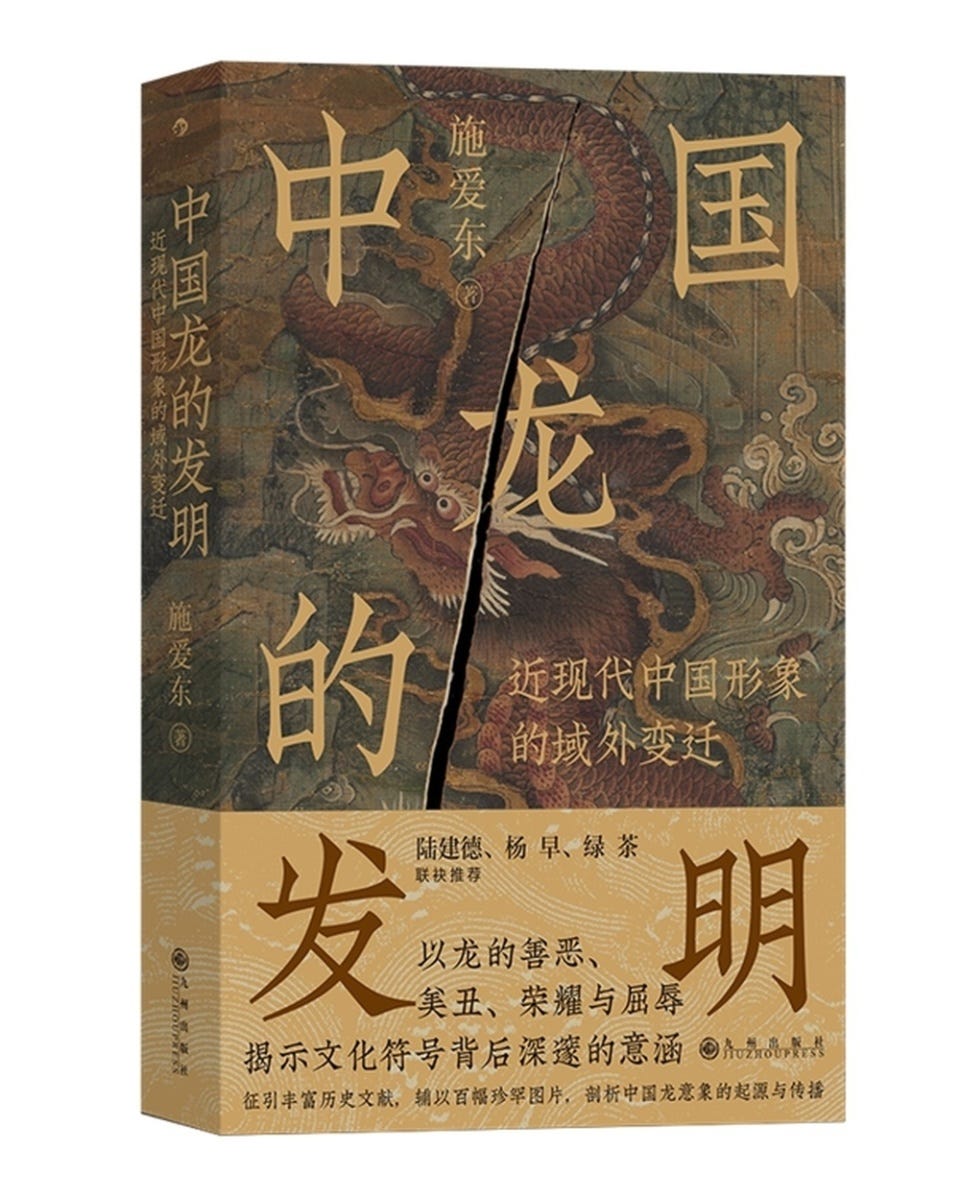

Shi Aidong is a researcher at the Institute of Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and Vice President of the China Folklore Society. His book, "中国龙的发明:16-20世纪的龙政治与中国形象 The Making of the Chinese Dragon: Dragon Politics and China's Image from the 16th to the 20th Century," was originally published in 2014. In the 2024 edition, the subtitle was changed to "近现代中国形象的域外变迁 The Transformation of Modern China's Image Abroad."

All pictures are added by me. —Yuxuan Jia

《中国龙的发明》修订版后记

The Making of the Chinese Dragon: Afterword for the 2024 Edition

As the Year of the Dragon approaches in 2024, I've been kept extremely busy. The whole nation is immersed in a "dragon atmosphere," with various cultural institutions contemplating how to craft the perfect "dragon narrative." Many people consider me an expert on dragon culture, and their all-out efforts for my articles and interviews left me in a state of unbearable distress. I am reluctant to monotonously repeat the same viewpoints and materials on dragon culture.

Over the years, despite my ongoing attention to new developments in dragon culture in hopes of discovering new topics, there haven't been any significant advancements honestly. The culture of the Chinese dragon has persisted for thousands of years, and any changes over the past decade are trivial in the grand historical context.

However, a "translation" topic from as far back as 2006 has continuously approached the center stage and has been thrust into the media spotlight again with the upcoming Year of the Dragon. This issue warrants a few remarks in this afterword.

In December 2006, Professor Wu Youfu, the Secretary of the Party Committee at Shanghai International Studies University, launched a major project "Shaping China's National Image," funded by the Shanghai Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science. When Wu briefed the press about the projects, he pointed to an important motive: "The English word for 'dragon' is perceived in the Western world as a domineering and aggressive behemoth. The image of 'dragon' often leads to some biased and arbitrary associations for foreigners who are not well-versed in Chinese history and culture."

Concurrently, Associate Professor Huang Ji of the School of Communication at East China Normal University persistently advocated for the "proper re-recognition of the dragon" by posting on major online platforms, suggesting the adoption of the English translation "loong" and cancellation of the wrong translation "dragon" as he believed this to be the fundamental way to prevent misconceptions of Chinese legendary beast.

Their proposal sparked wide and intense discussions on the Chinese internet, with strong voices on both the against side and the for side. The debate continued, and in October 2007, a group of "dragonologists" gathered in Lanzhou for a dragon culture seminar, which subsequently released the "Declaration of the First Chinese Dragon Culture Forum in Lanzhou", proposing the initiative to "correct the 'foreign name' of the Chinese dragon." "The Chinese dragon and the Western dragon are worlds apart. The Chinese dragon, with its wondrous form, symbolizes justice and good fortune, while the Western dragon, with its grotesque appearance, embodies evil and disaster. The Chinese dragon should be translated as 'loong' in English to showcase this distinction," reads the Declaration.

As these dragonologists explained, "loong" is derived from the English word "long," which resembles the pronunciation of "龙" (Lóng) in Chinese. The meaning of 'long' also aligns with the dragon's physical attributes, and the double 'o' evokes the image of the dragon's large, mystical eyes, capturing its essence in both shape and spirit. Therefore, they urged the Chinese to discuss with the Western governments to adopt this suggestion, adding it to English dictionaries.

In the ensuing dozen years, these dragonologists tirelessly campaigned, striving to change "dragon" into "loong." As the Year of the Dragon approaches in 2024, they hope to ride the tide of this auspicious moment and see their dreams soar like dragons leaping over the carp gate. [In Chinese mythology, carp who leap over the dragon Gate would become dragons.]

But will changing the name really have such an impact? If it did, many would have rushed to change their names to "Jack Ma."

We all know that the symbol of France is the Gallic Rooster (Le Coq Gaulois). In the contemporary Chinese context, roosters do not hold a favorable reputation. Should the French government consult with the Chinese government to rename the Gallic Rooster in Chinese to Gáolú Lèkě [a phonetic transcription of Le Coq Gaulois in Chinese pinyin]?

In fact, the first to translate the Chinese dragon as "dragon" was Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), the greatest sinologist in Sino-Western cultural exchange. His love for China was profound; he lived, died, and was buried in China. Ricci doffed his Western coat for Confucian robes, delving deeply into sinology. Esteemed by Ming dynasty scholars, he was honored as the "Confucian Scholar of the West." Didn't he not recognize the disparities between the Chinese dragon and the Western dragon? Of course he did. Prior to him, all other missionaries directly translated dragon as "Serpentes" (great serpent). Ricci's translation, the finest of his time, was swiftly embraced by Western society.

So, did Ricci's translation lead to feelings of animosity towards China in Western society? The answer is no. Early European missionaries to China objectively reported the status and usage of the dragon design in China. Their writings often associated dragon patterns with royal grandeur. This portrayal captivated the European romantic aristocrats who were already enchanted by the mystique of the East. In the 17th and 18th centuries, garments adorned with dragon, phoenix, and qilin motifs were fervently embraced by the aristocracy in cities like London and Paris, esteemed for their ineffable beauty. During this era, all of Europe buzzed with wondrous and romantic imaginings of exotic China. Many museums still preserve exquisite dragon-patterned porcelain, custom-made in China for the European upper class, showcasing designs that are intricate and refined, devoid of any hint of "evil."

By the 19th century, trade conflicts between China and Great Britain, along with the two Opium Wars, significantly altered Europe's attitude towards China. The previous century's fervor for China gave way to disdain. The Chinese dragon, once admired, fell out of favor with Europeans. After the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, China's image in Europe reached an unprecedented low, leading to a surge in negative caricatures depicting the Chinese dragon.

During World War II, as China was part of the anti-fascist alliance, the portrayal of the Chinese dragon in media from the anti-fascist camp, including the United States and the United Kingdom, was consistently positive. Whether in cartoons or texts, there was no discrimination against or defamation of China due to the translation of the Chinese dragon.

In fact, almost all authoritative Western dictionaries provide objective descriptions of the Chinese dragon. For example, the Oxford Dictionary of English states, "Dragon, a mythical monster like a giant reptile. In European tradition, the dragon is typically fire-breathing and tends to symbolize chaos or evil, whereas in East Asia it is usually a beneficent symbol of fertility, associated with water and the heavens." Similarly, the Encyclopaedia Britannica mentions, "Dragon, in the mythologies, legends, and folktales of various cultures, a large lizard- or serpent-like creature, conceived in some traditions as evil and in others as beneficent." These entries clearly differentiate the cultural differences in dragon symbolism and do not deliberately malign the Chinese dragon.

As early as 2001, UNESCO adopted the "Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity," establishing respect for the cultural traditions of different ethnicities and regions as a common code of action for the global community. Since Ricci's time, the translation of "dragon" for "龙/龍" has been in use for over 400 years, and Westerners understand the Chinese dragon as clearly as the Chinese understand the Western dragon. To think that Western countries are so brainless as to use such a simplistic and foolish translation of "dragon" as a tactic to belittle China is truly a product of the dragonologists' closed-minded imagination.

Even in China, the dragon possesses dual characteristics. In folklore, evil dragons far outnumber benevolent ones, with many legends featuring heroes battling dragons. One of the most famous stories is about the Heilongjiang [Black Dragon River]. In this tale, the little white dragon often flooded the area, causing misery for the people. Eventually, the little black dragon, known as "Bald-tailed Old Li," fought the white dragon in a battle of good versus evil. When the little black dragon surfaced, people threw in loads of bread; when the little white dragon surfaced, they hurled in stones. Starved and injured by the stones, the little white dragon was ultimately defeated by the little black dragon, leading to the river being named Heilongjiang.

The perception of a dragon, whether benevolent or malevolent, revered or reviled, is shaped not by its name but by people's emotions and attitudes. The little white dragon is handsome, but people hurl stones at it. The little black dragon, dark-colored, bald-tailed, and ugly, with an unflattering name like "Bald-tailed Old Li," receives offerings of bread. This principle holds true internationally. When viewed as alien, no matter how pleasant your name is, you will be depicted negatively. When seen as a friend, even a name like "mouse" can be endearing, as in Mickey Mouse.

January 19, 2024