China should "invest in reform" to lift demand, says Bai Chong’en

Tsinghua Econ Dean proposes a two-track agenda of debt resolution and health insurance reform, backed by rule-based, targeted central bank support.

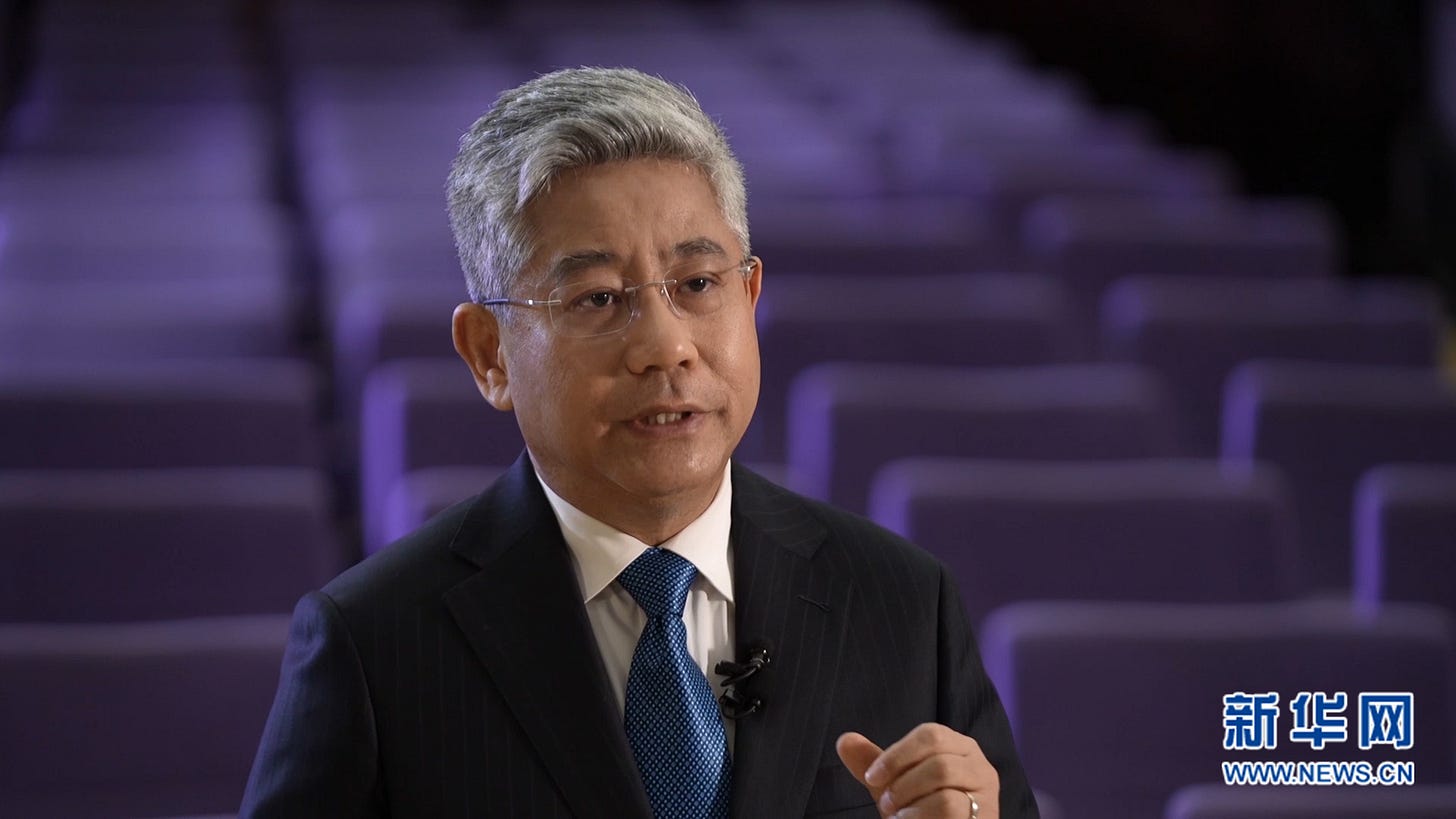

Bai Chong'en, Professor and Dean at the School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, and Academic Committee Member of the China Finance 40 Forum (CF40), argues policymakers should “invest in reform” by using tightly coordinated fiscal–monetary coordination to finance the transition costs of structural change.

Bai delivered the speech at a CF40 seminar on 25 January, 2026. CF40 published the text on its official WeChat blog on 6 February.

Founded in 2008 in Beijing, CF40 is a leading independent think tank in China. As a membership institution, it features 40 members around 40 years old from regulators, academia, and the market. CF40 also hosts the annual Bund Summit; a transcript of a 2025 Bund Summit roundtable is available on The East is Read.

投资于改革——兼论财政货币政策协同

Investing in Reform—On Fiscal and Monetary Policy Coordination

Abstract: With China’s domestic demand still weak and prices subdued, now is an opportune time to invest in reform. Through close fiscal–monetary coordination, policymakers can finance the transitional costs of structural reforms and pursue two goals at once: short-term demand support and long-term institutional improvement.

The key is to set clear boundaries. Monetary policy should work in lockstep with fiscal policy to enable expansionary support for reform, but that support must be explicitly temporary and targeted—provided only when deflationary pressures are pronounced, and withdrawn in an orderly manner once the economy returns to normal inflation to prevent an inflation overshoot. Funding should also be strictly earmarked for the transitional costs of reform, in exchange for stronger long-run fiscal sustainability.

Two priorities stand out: resolving local government debt and reforming the “dual-track” health insurance system. Unlike Modern Monetary Theory, this approach treats reform as the premise and policy coordination as the instrument—raising aggregate demand in the short run while ultimately improving economic efficiency and social equity. Although a period of mild inflation may imply an “inflation tax,” the overall effect on income distribution can be positive if the benefits of reform accrue more to lower-income groups.

I. Now Is an Opportune Time to Invest in Reform

China’s current price dynamics are relatively weak, and domestic demand is insufficient. The data show that both CPI and PPI are at low levels, with the weakness particularly pronounced in PPI. In addition, in recent years nominal GDP growth has at times fallen below real GDP growth, reflecting the combination of weak demand and subdued prices. Against this backdrop, achieving a moderate level of inflation would bring multiple benefits, including stabilizing nominal prices for assets such as real estate.

How can we reach the goal of moderate inflation? One important approach is to implement stimulus policies, among which fiscal stimulus is a key instrument. There are different views on where fiscal resources should be directed. In the past, the focus was primarily on investing in “things,” such as infrastructure and other physical assets, but the marginal impact of this approach has gradually weakened. Today, there is broad emphasis on “investing in people,” which is undoubtedly a step forward. Yet “investing in people” also faces challenges. For example, if the funds are used to improve social security, such measures are often irreversible—once benefits are raised, it is difficult to reduce them later in response to changing economic conditions or other fiscal pressures. This makes it necessary to carefully assess the appropriateness and sustainability of benefit increases. Moreover, the short-term effects of direct transfers—simply giving cash to consumers—remain unclear; and while programs such as “trade-ins” can boost demand for durable goods today, they may also pull forward future consumption and erode demand later.

Beyond these measures, resolving local government debt is another possible avenue, but it raises concerns about moral hazard: once local debt is relieved, it may grow rapidly again. If the central government issues debt to swap out local liabilities, it is also worth guarding against the possibility that this could squeeze future fiscal space at the central level.

In this context, I would like to propose a concept: investing in reform.

At present, reforms in several key areas are urgently needed. Take local government debt as an example. The underlying problems have accumulated over a long period, and any solution must balance short-term stabilization with long-term consequences—reducing current risks while avoiding moral hazard triggered by bailout expectations. Another example is the “dual-track” structure within the social security system: in both pensions and health insurance, there are significant benefit gaps between employee-based schemes and schemes for urban and rural residents. This institutional segmentation creates many problems, but reform is costly. Simply raising resident pension or health benefits may improve livelihoods, yet the irreversibility of such increases can put fiscal sustainability under pressure.

Now imagine an ideal scenario: ignoring real-world constraints, we design a long-run steady-state optimum—one that both safeguards fiscal sustainability and delivers a fairer and more efficient social security system. In practice, however, moving from the current system to that ideal steady state often entails substantial transition costs, including one-off expenditures, compensation payments, and various frictions arising from institutional switching.

Therefore, at a time when fiscal stimulus is urgently needed, we might treat “investing in reform” as a policy option: first, design reform plans scientifically (covering, for example, the local fiscal system and pension and health insurance institutions), and estimate their transition costs with precision; then, using the current stance of relatively accommodative fiscal and monetary policy, concentrate resources to pay those transition costs. In this way, the policy can deliver stimulus in the short run while advancing structural reform in the long run—without increasing long-term fiscal burdens. Indeed, it may reduce the future operating costs of the system. This is the core meaning of “investing in reform.”

We can recall the “three arrows” of Abenomics: the first is monetary policy, the second is fiscal policy, and the third is structural reform. Here I offer a suggestion: treat structural reform and the first two arrows—fiscal and monetary policy—as an integrated package, so that short-term fiscal and monetary stimulus helps overcome the obstacles that inevitably arise during structural reform. That is the central idea I want to convey.

Why is now a good time to pursue this approach? First, we face the pressure of insufficient demand. Under such conditions, strengthening fiscal and monetary policy is unlikely to trigger severe inflation; on the contrary, it can help us escape the risk of persistent price declines. If policies are implemented properly and expectations are well managed, it may be possible to build a virtuous cycle of expectations, achieve moderate inflation, and advance reform smoothly. I would call this situation an “almost free lunch”—one in which obvious negative effects are hard to see. Of course, there are potential risks: if implementation is weak or expectations are mismanaged, a mistaken belief may form that “monetary policy will always step in to backstop things,” which could create moral hazard. But with careful design and effective management, the benefits should outweigh the costs, and the overall cost can be relatively low.

In fact, China has done something similar before. The banking reforms launched in the late 1990s—especially the reforms beginning in 1999–2000—and the large-scale disposal of nonperforming assets in the following years closely resemble this approach.

Specifically, at the end of 1997, the central government convened the first National Financial Work Conference and made clear that it would begin tackling nonperforming assets at state-owned banks. A series of measures followed, including recapitalization, comprehensive audits, the adoption of a five-category loan classification system, the carving-out of nonperforming assets, and the establishment of four asset management companies to take over those assets. Between 1999 and 2000, a one-off transfer of nonperforming assets totaling RMB 1.4 trillion was carried out.

From today’s perspective, RMB 1.4 trillion may not seem enormous, but relative to the economy at the time it was very large: in 1999, total national fiscal revenue was only RMB 1.14 trillion, meaning the one-off transfer exceeded annual fiscal revenue; and GDP that year was RMB 8.21 trillion, so the transferred assets amounted to about 17% of GDP. Did such a large operation trigger serious inflation? The answer is no. This suggests that under certain conditions, even very forceful policy actions do not necessarily lead to high inflation. Of course, today’s environment differs from that time, but at least there is a historical precedent.

More importantly, a consensus in favor of reform was formed at that time. By 2002, the second National Financial Work Conference further clarified that ownership reform was essential so that state-owned banks would truly bear risks on their own. This consensus emerged during China’s transition period after joining the WTO and was intended to resolve the fundamental problems of the state-owned banking system.

While deciding to carve out nonperforming loans, the central government also pushed banks to establish genuinely market-oriented mechanisms, with ownership reform at the core. Subsequent reforms broadly pursued three objectives: clarifying ownership rights, separating government from enterprise operations, and strengthening internal management; and they set three major tasks: restructuring state-owned banks into joint-stock companies and listing them, establishing modern corporate governance, and substantially lowering nonperforming asset ratios. A banking regulator was also established to strengthen supervision. In this process, the listing of Bank of China (Hong Kong) became an important milestone.

Later, under former PBC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan, an overall reform blueprint and implementation plan took shape, mobilizing national resources in a systematic way—including fiscal resources, state assets, the central bank’s balance sheet, and foreign exchange reserves. One particularly innovative step was to use foreign exchange reserves to provide capital support for the joint-stock reform of state-owned banks.

Beyond the innovation in fiscal restructuring, another striking feature of this case was the simultaneous push for corporate governance reform, aimed at building a standardized, transparent, and market-based institutional framework.

At the time, China’s banking sector faced an extremely severe situation: nonperforming assets had piled up, and the market widely worried about the stability of the banking system. Yet the macro environment also featured weak aggregate demand and some deflationary pressure. In that context, China adopted unprecedented policy measures—carving out nonperforming assets amounting to 17% of GDP in a single operation in 1999–2000, followed by multiple additional rounds of disposal. These steps effectively reduced risks in the banking system in the short run, replenished capital, and helped banks resume normal operations. More importantly, they created the necessary conditions for subsequent commercial bank reforms. After all, if banks had remained burdened by massive nonperforming assets, it would have been impossible to pursue joint-stock restructuring, public listings, or the introduction of strategic investors.

In this sense, the nonperforming-asset swap was a classic case of “investing in reform”—using an organic combination of fiscal and financial policies to clear the path for deeper institutional change. Of course, the process mobilized enormous financial resources, but it did address a series of critical problems.

II. Two Directions

Against today’s backdrop of weak demand and subdued prices, what else can we do? I would suggest two possible directions. Which should take priority requires a comprehensive judgment. I have my own view, but I trust those here have more professional assessments. The first direction is to address local government debt. At present, local government debt not only constrains local development capacity; its hidden-debt risks are also substantial and have a clearly negative impact on market expectations—this is widely recognized, so I will not elaborate further. The second direction is reform of the social security system, especially the dual-track structure in pension and health insurance. I would recommend tackling health insurance first.

First, the near-term problems created by the dual-track split in health insurance (employee insurance versus resident insurance) are particularly acute. It not only suppresses residents’ medical consumption, but also holds back the development of the broader health industry. Health insurance authorities face enormous pressure to control costs. While some cost-control measures are justified, excessive cost containment can at times undermine a reasonable return mechanism for pharmaceutical and medical-device R&D. Moreover, there is significant room for growth in medical services: the public has strong demand for better healthcare services; healthcare expansion can also create many high-quality jobs; and inadequate medical coverage has become a bottleneck preventing this potential from being realized. If reform can deliver two gains at once—moderately increasing health insurance spending while broadening the system’s revenue sources—it would lay a foundation for long-term sustainability.

To be sure, the transition from the status quo to an ideal state is extremely complex. Specifically, for local government debt, the short-term objective is to defuse risks in the existing stock of debt, while the long-term task is to pursue fundamental reforms of the local fiscal system and local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). For the health insurance system, the short-term option could be to raise benefits under resident insurance; over the long run, the goal should be to bring the employee and resident schemes partially into alignment, narrow the benefit gap between them, and consider increasing health insurance contributions.

At present, local governments face heavy interest-payment burdens. Although they have been permitted to issue large amounts of new, lower-rate debt to swap out old debt, the debtor has not changed and the interest burden remains. Combined with the sharp decline in land-related fiscal revenues, local fiscal stress has intensified further. In addition, many special local government bond projects generate returns below their financing costs, raising concerns about long-run sustainability. On top of that, the pandemic over the past three years significantly increased local fiscal burdens. Our calculations suggest that although later measures—such as allowing swaps using longer-maturity debt quotas—have temporarily eased pressure, an excessively high debt ratio still severely limits local governments’ policy space and capacity to act. We therefore urgently need a systematic plan to address this predicament.

In the short term, one option is for the central government to issue treasury bonds to swap for local government debt. In this process, the monetary policy authorities must coordinate closely: when new treasury bonds are issued, the central bank could absorb part of the issuance through a moderate balance-sheet expansion, thereby reducing the shock to financial markets. However, if we merely swap local debt without simultaneously pursuing deeper reforms of the local fiscal system and LGFVs, we will fall back into the moral-hazard problem noted earlier: once old debt is resolved, new debt may quickly accumulate again, potentially creating an even more serious situation. We therefore need a comprehensive program that can both relieve today’s debt pressures and drive long-term institutional change.

In an ideal configuration, the long-term objective should be fundamental reform of both the fiscal system and financing vehicles. Fiscal reform should recalibrate the scope and scale of local revenues and expenditures, improve the division of administrative responsibilities and spending obligations between the central and local governments, enable local governments to achieve a basic balance between revenues and expenditures under normal conditions, eliminate hidden debt, and significantly reduce reliance on land finance. This reform is extremely complex and far-reaching, but continued delay will only make the accumulated problems more severe. As for reforming financing vehicles, the core goal is to ensure they no longer function as fiscal tools of local governments, but truly transform into independent market entities that bear their own profits and losses. I will not expand on this here, but the direction is clear.

During the transition, given the enormous stock of local debt already in place, we need to draw on the experience of the banking reforms of that era. Just as nonperforming assets were carved out to let banks “travel light,” creating the conditions for subsequent joint-stock reform, today we should also dispose of existing debt in an orderly manner to clear obstacles for reform of local public finance and financing vehicles. Of course, fiscal outlays and treasury issuance on such a scale would inevitably shock financial markets without corresponding monetary policy cooperation, so close coordination with monetary policy is essential. The most straightforward approach is this: after the fiscal authority issues treasury bonds, the central bank purchases an equivalent amount in the secondary market, thereby avoiding a sharp rise in interest rates or the crowding-out of private-sector financing. Such operations must be premised on sound expectations management, ensuring that the market understands the policy’s staged nature and goal orientation. In addition, if the interest rate on the debt associated with the central bank’s balance-sheet expansion is below nominal GDP growth, then over time the ratio of that debt to GDP will naturally decline. For this reason, such policies should have clear exit conditions and mechanisms. The core policy objective is to sustain moderate inflation, while strictly guarding against high inflation and sharp swings in asset prices.

Turning to health insurance reform: at present, employee health insurance covers roughly 380 million people, while resident health insurance covers about 950 million, and benefit levels differ markedly. Over the long run, we hope to gradually narrow this gap. Consider an ideal scenario: as the economy develops and the employment structure improves, the vast majority of households have at least one employed worker, and many have two. If employee health insurance could be expanded from covering only the worker to covering the worker’s entire household (including spouse and children), then in theory the employee scheme could cover almost the entire population. Using the family as the insured unit is a common international practice. This idea requires cost estimation.

Suppose a typical household structure today is two working parents with one or two minor children, and children are covered by their parents’ health insurance only until age 22. Under that assumption, the incremental cost would be relatively manageable. The key is strict enforcement of existing contribution requirements. In the employee scheme, the pooled portion is funded by employer contributions, at roughly 6% of wages, but in some cases, contributions are not made in full. Even if a funding gap remains after strict enforcement, it would still be feasible—within socially acceptable bounds—to raise the contribution rate moderately to a reasonable level. After all, moving from individual coverage to family coverage expands the protection scope, so a measured increase in contribution rates, with a well-paced adjustment path, is also reasonable.

However, this vision is a long-term target. Over a lengthy transition, substantial costs still need to be borne. We have done some preliminary calculations. For example, one transitional option is to unify inpatient coverage first—because inpatient needs are highly inelastic, and hospitalization frequency is similar for employees and residents, so improving inpatient benefits under the resident scheme is unlikely to induce excessive utilization. Estimates suggest that if inpatient reimbursement levels for all resident-insurance participants were raised to employee-insurance standards, the additional annual spending required would be about RMB 900 billion. A more comprehensive alignment option (given data limitations, only a rough estimate based on public information) suggests that if the benefit gap were narrowed more broadly—so that more than 900 million resident-insurance participants receive protection close to the employee-insurance level—the additional annual spending would be around RMB 1.1 trillion.

Of course, RMB 1.1 trillion per year is not a small number. But under today’s macro environment of low inflation and weak demand, the cost of moderately increasing fiscal spending is relatively low. As noted earlier, the economic cost of expansionary policies is smaller when prices are subdued. As for which reform to advance, and with what structure and intensity, I am offering only one line of thinking here for further discussion.

III. Defining Boundaries and Exit Rules for Monetary Policy Is Key to the Success of “Investing in Reform”

A crucial premise is that monetary policy support for fiscally driven structural reform must be governed by clear boundaries. Without such boundaries, monetary policy may come under excessive strain—what I would call “overexpansion.” Concretely, such support should be activated only when deflationary pressures are pronounced; once expected deflation risks recede and the economy returns to a path of moderate inflation, it should be withdrawn decisively. At the same time, the use of funds must be strictly limited to paying the transitional costs of reform, rather than plugging long-term fiscal unsustainability. Our aim is to strengthen long-run fiscal sustainability through reform itself, while covering short-term transition costs with purpose-specific treasury issuance—what we might call “price-stability treasury bonds.”

This framework depends heavily on close fiscal–monetary coordination, and the central bank must also manage interest rates effectively to ensure smooth policy transmission. We emphasize consistency in policy stance: fiscal and monetary tools should work in the same direction, jointly serving structural reform and macroeconomic stability.

Some may worry that this is simply another version of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Here we need to be explicit: the core of this proposal is to advance structural reform, which is fundamentally different from how MMT understands the role of fiscal policy. MMT often downplays fiscal discipline and the need for reform, whereas we emphasize that reform is the prerequisite and that fiscal–monetary support is only a means to create the conditions for reform.

In addition, the exit mechanism must be governed by clear rules. Looking back at the “three arrows” of Abenomics, structural reform was not implemented particularly well, and U.S. monetary policy after the pandemic also failed to advance structural reform. These experiences remind us that without solid reform, pure monetary or fiscal stimulus is difficult to sustain.

China’s economy today faces the dual pressures of supply-side shocks and weakening demand, so a period of moderate inflation can be constructive. One condition mentioned earlier is that interest rates should remain below the economy’s growth rate—and we are currently in such a situation. Some studies show, in theory, that under certain conditions—such as a liquidity trap—fiscal stimulus financed by money can be more effective than stimulus financed by debt. One important reason is that it avoids triggering fears of sharply higher future taxes as government debt jumps. With good design, such concerns can be avoided.

We combine “investing in people” with “investing in reform.” Many “investing in people” initiatives—such as social security, healthcare, and education—require long-term institutional design, and to realize that long-term design we can use today’s fiscal and monetary stance to overcome the costs of transition. If we do so, who benefits, and who might lose? Some may question whether moving from low prices to about 2% moderate inflation amounts to an “inflation tax” on households, reducing their welfare.

It is true that, from a price perspective, households may bear some cost as prices rise. The key, however, is how the additional spending is used. If the new spending is directed primarily toward livelihood-related reforms—such as health insurance reform—the main beneficiaries will be middle- and lower-income groups.

Inflation is often thought to worsen income distribution, but if the spending is structured so that lower-income groups benefit more, the overall effect on distribution could be positive. As asset prices recover, employment improves, and public services strengthen, the broader population will benefit as well—especially middle- and lower-income households.

The most straight forward way to lift demand is through public investment. Reform needs to be justified on its own merits, not because it “lifts demand”