China adds science funding for young global talents as Trump cuts U.S. research budget

Chinese universities jump at a "newly-added round" of funding at China's NSF to encourage "more" leading scientists under 40 to move to the East.

The government-run National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) has just opened an extra batch of funding opportunities wooing scientists from outside China with PhD degrees under the age of 40, as the Trump administration slashed federal funding for science and technology research, including to the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF).

The NSFC said on July 30, 2025 that

为进一步完善科学基金人才资助体系,充分发挥科学基金引进和培养人才的功能,吸引更多海外优秀青年人才回国(来华)工作,国家自然科学基金委员会(以下简称自然科学基金委)现启动2025年新增批次优秀青年科学基金项目(海外)申报工作。

To further improve the talent funding system of the NSFC , fully leverage its role in attracting and nurturing talent, and encourage more outstanding young talents from overseas to return to (or come to) China for work, the National Natural Science Foundation of China is now launching the application process for the newly added round of the Excellent Young Scientists Fund (Overseas) in 2025.

The advertisement says applicants should be born after January 1, 1985, hold PhD degrees, and primarily conduct research in natural science, technology, and engineering. They should have 36 consecutive months of formal working experience outside China in well-known universities, research institutions, and research departments within companies after their PhD and before September 15, 2025, with shortened working experience requirements for exceptional applicants.

They should “have achieved scientific or technological outcomes recognized by peers in the field, and demonstrate the potential to become an academic leader or outstanding talent in the discipline,” according to the notice.

NSFC funding for successful candidates totals between one million yuan ($140,000) and three million yuan ($418,000) over three years.

The NSFC launched its program targeting scientists based outside China in 2021. Since then, it usually opens up funding opportunities in the early months of the year, except April 2023, when it opened up for an extra week to “mitigate the impact brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

After a routine announcement in February 2025, the NSFC made clear on July 30 that the opening-up last week is a “newly added round” (新增批次) to attract “more” (更多) scientists from outside China. However, the exact amount of new funding hasn’t been disclosed.

Applicants submit through a host Chinese institution, typically a university or a research institution registered in NSFC’s system. After two levels of reviews, funding is dispersed to the scientists via the host institution, adding to the latter’s research budget.

Many Chinese universities have jumped on the announcement, almost simultaneously inviting overseas scientists to apply for the new funding through them. An incomplete list of Chinese universities making public invitations includes Peking University, Renmin University of China, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Jilin University, etc.

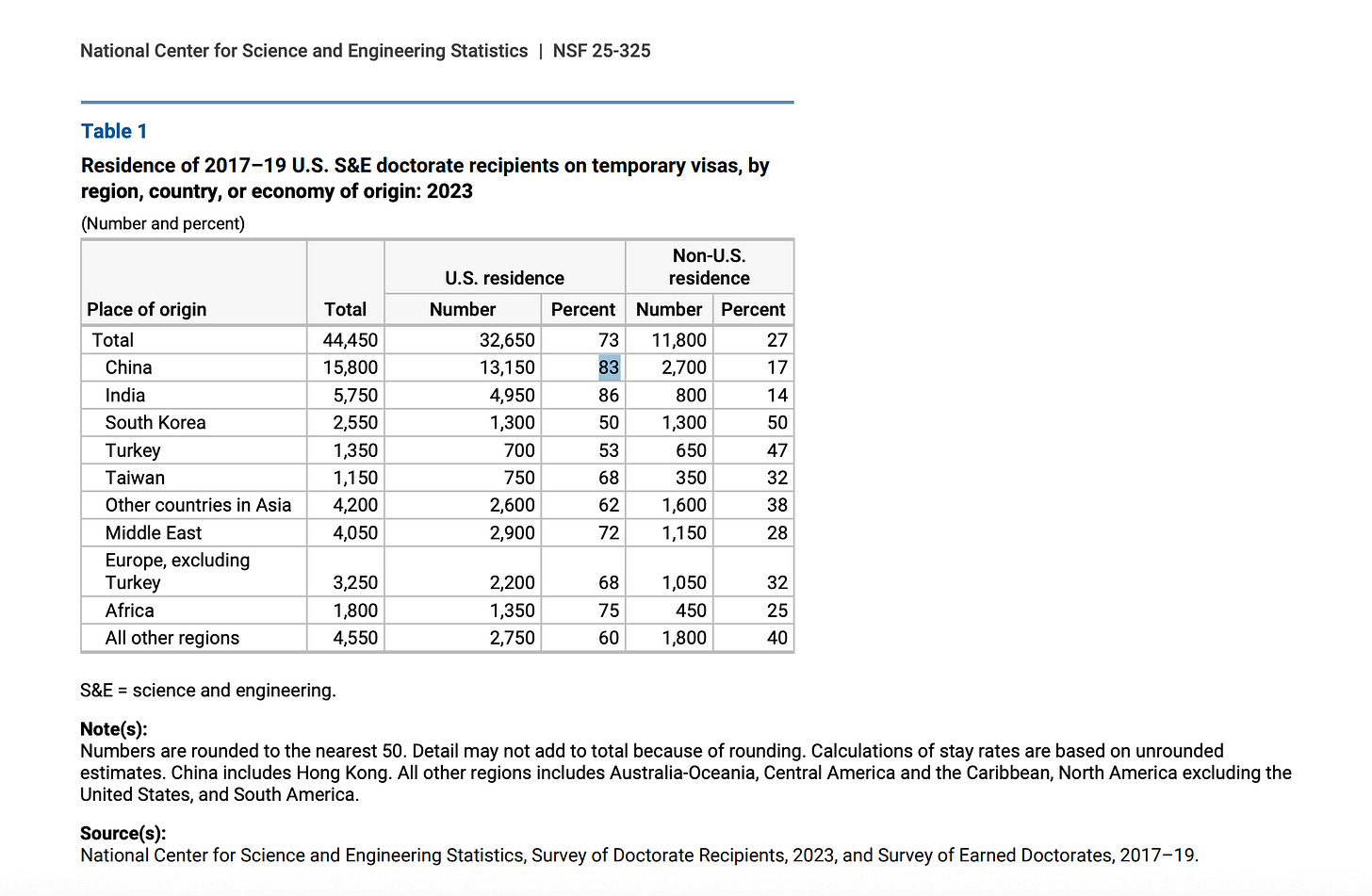

China has long suffered what is often called a “brain drain” of scientific and technical talent, as a very high proportion of China‑born PhD graduates in U.S. universities choose to remain in the U.S.

A 2023 survey by the U.S. National Science Foundation found that 83% of China-born PhD recipients in science and technology who got their degrees in America between 2017 and 2019 remained in the United States approximately 5 years after graduation. The number is “significantly higher than the average across all countries of origin,” says the NSF report.

The Chinese government has launched various campaigns to attract science and technology talent, including those with no Chinese heritage, to come to China.

Funded scientists in the NSFC program must resign from their overseas jobs and work full-time in China, addressing concerns from suspicious observers who claim that holding two simultaneous jobs across the Pacific often means China is stealing from America.

The new round of funding also comes at a time of dramatic cuts to science research funding in the U.S., which many claim will help China attract global talent.

An important extension. There’s an opportunity for a new global education order, as I have recently argued: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202507/16/WS6876e853a31000e9a573c381.html

President Bush and Congress limited fetal stem cell research.

Following that restriction on U.S. research, ChatGPT says China made the following gains:

“Here’s a timeline of key developments in China’s fetal and embryonic stem cell research during the Bush restriction years (2001–2008), focusing on work that either used fetal tissue–derived stem cells or was enabled by the absence of U.S.-style limits:

⸻

🔹 2001

• Aug 9 – President Bush announces restrictions on U.S. federal funding for new embryonic stem cell lines.

• Oct – China’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and Ministry of Health issue Ethical Guidelines for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research, explicitly permitting work using:

• Surplus IVF embryos (<14 days old)

• Fetal tissue from voluntary abortions (with consent)

• Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) for research

• Several Chinese labs, notably at Peking University, Shanghai Second Medical University, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, begin new derivation projects.

⸻

🔹 2002

• Shanghai Second Medical University announces the derivation of multiple new human embryonic stem cell (hESC) lines, including some from fetal germ cells.

• Early reports in Chinese journals describe successful differentiation of hESCs into neuronal precursor cells.

⸻

🔹 2003

• Researchers at Peking University develop hESC lines from fetal tissue obtained via therapeutic abortions, isolating neural stem cells capable of differentiating into dopamine-producing neurons (a target for Parkinson’s research).

• Cell Research publishes one of the first comprehensive reports of hESC lines derived entirely within China.

⸻

🔹 2004

• A team at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai publishes methods for growing stable hESC lines and differentiating them into cardiomyocytes and neural cells.

• International collaboration: Some U.S. and European scientists obtain Chinese hESC lines through joint projects, bypassing Bush-era restrictions.

⸻

🔹 2005

• Chinese scientists report in Stem Cells journal that fetal-derived neural stem cells survived and integrated into rat spinal cords, showing partial functional recovery.

• Shanghai groups announce somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT)–based embryonic stem cell derivation in primates, something U.S. federal labs could not pursue with federal funding.

⸻

🔹 2006

• Cell Research publishes studies on directing fetal-derived stem cells to differentiate into insulin-producing cells for diabetes models.

• Clinical pilot studies begin in China using fetal neural stem cell grafts in patients with spinal cord injury and cerebral palsy — controversial internationally, but legal under Chinese rules.

⸻

🔹 2007

• Reports emerge of fetal mesenchymal stem cells (from aborted fetuses) used experimentally to treat liver cirrhosis in small human trials in Beijing and Guangzhou.

• Chinese labs demonstrate hESC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells in animal models of blindness.

⸻

🔹 2008

• A multicenter group publishes data on human fetal-derived neural stem cells transplanted into patients with traumatic brain injury — claiming safety and modest neurological improvement.

• By this point, China had one of the largest banks of hESC lines in the world, many derived from fetal sources, and was supplying lines for research abroad.

⸻

📌 Summary:

During 2001–2008, China’s permissive policies allowed it to:

• Derive new hESC lines from both IVF embryos and aborted fetal tissue.

• Continue SCNT experiments.

• Begin controversial pilot clinical uses of fetal stem cells that were off-limits in the U.S.

• Become a source of cell lines and collaboration for Western scientists constrained by U.S. law.

⸻

If you want, I can list specific U.S.–China collaborative projects that arose because of Bush’s restrictions, showing how researchers shifted work overseas to access Chinese fetal stem cell lines. That’s where the political implications get interesting.”