Calculating the cost of childbearing in China: the formidable factor behind country's dwindling birth rate

Part I of a Peking University session delving into the factors behind population challenges in China, particularly from the perspective of women.

On Nov. 11, 2023, the National School of Development at Peking University hosted a session on the employment and family choices of Chinese women. This event took place amid the escalating challenge of China's declining birth rate, which resulted in a decrease of 2.08 million in the nation's total population in 2023. Additionally, the session's theoretical framework was informed by the work of Claudia Goldin, the 2023 Nobel Laureate, honored for her comprehensive research into women's earnings and their participation in the labor market throughout centuries.

The following is the first lecture of the session, presented by Huang Wei, an associate professor with tenure at the National School of Development of Peking University. He earned a Ph.D. degree in economics at Harvard University in 2016.

Huang's lecture provided an extensive record of the costs associated with childbearing in China, covering both male and female groups and spanning various time periods. However, for an in-depth exploration of the costs exclusively shouldered by women and for detailed policy proposals to alleviate these costs, the other lectures in the same session are recommended, as they present a more comprehensive analysis. The East is Read and Pekingnology will roll out all the lectures, plus a dialogue, from the session, so stay tuned.

The Chinese transcript of Huang's lecture is available on the official WeChat blog of the National School of Development.

The study I'm sharing concerns the cost of childbearing in China. What are the costs associated with childbearing in China? Where do these costs come from? How high are the costs?

Before the 1980s, China maintained a relatively high birth rate. This rate declined rapidly following the implementation of the family planning policy [1970]. After the introduction of the one-child policy [1979], the birth rate continued to decrease. It was not until recently, with policies encouraging childbirth unveiled [two-child policy in 2015 and three-child policy in 2021], that China's birth rate has seen a slight resurgence, although further improvement is needed.

There is a heated discussion about why China's birth rate is relatively low and what people can do about it.

Classification of Childbearing Costs

One significant reason for the low birth rate is the high cost of childbearing. Economists categorize costs in several different ways.

Opportunity cost of childbearing

In economics, "opportunity cost" refers to the benefits lost by not engaging in alternative activities to pursue a particular action. For women, this might involve forgoing parts of their career, such as employment, pay raises, and promotion opportunities, for childbearing. Men might also have to make sacrifices. Economists describe this with the term "child penalty," meaning that a couple's careers have to give way to raising children to a certain extent.

In addition to the child penalty, there are many other sacrifices after having a child. For example, the freedom to hang out at will is reduced, and the ability to freely manage one's time becomes more limited.

Direct costs of childbearing

The "costs of childbearing" currently under widespread discussion primarily refer to the direct costs of raising a child which mainly include:

Maternal and infant care costs, such as expenses for maternity matrons, maternity services, postpartum care centers, and mother-and-baby food products. The process of childbearing also incurs many expenses. For example, the cost varies between public and private hospitals, and so does the price for different levels of services.

Educational costs, including expenses for nursery schools, tutoring, and school selection fees.

Costs of house purchasing and household supplies. Many families living in one-bedroom apartments have to consider moving to bigger ones after having a child. Raising a child also involves purchasing numerous household items. A common experience is that when traveling with a young child, the kid's items need to be packed in the largest suitcase, while a smaller case is enough for the parents' articles. Some parents will also plan for their children's future and buy housing for them in advance. This indicates the significant cost of purchasing items for a child.

Dynamic Impact of Childbearing on Labor Supply

Both men and women may have to give up certain opportunities in the labor market due to childbirth, which could impact the labor supply.

Figure 1 displays the dynamic changes in employment rates or labor supply for Chinese men and women before and after having children, using the dynamic analysis method proposed by Henrik Kleven, a professor of economics at Princeton University. It is apparent that in China, women's labor supply significantly declines by nearly 30 percentage points in the year of giving birth to babies, then gradually increases year by year, reaching the highest point around when the child turns eight, which is when the child starts elementary school and requires slightly less full-time care from the mother.

In contrast, men's labor supply immediately rises after their children are born. In some research papers, this is sometimes referred to as a "fatherhood bonus." But I don't think fathers are rewarded a "bonus" after childbirth, as they need to work doubly hard to create better conditions for the family after having a child. It is tough for both mothers and fathers.

Figure 2 primarily focuses on the analysis of women. The graph shows that, whether in the period from 2000 to 2005 or from 2010 to 2015, the trends in women's work-related changes before childbirth are almost identical, with a similar sharp decline in labor supply during the year of giving birth. In the recovery period after childbirth, women who gave birth in earlier years were able to return their labor supply to pre-birth levels through effort; however, women who gave birth in later years could hardly return to their pre-birth levels. This may reflect changes in the employment environment between 2000 and 2015, where despite their efforts, women still have to make significant sacrifices in their careers as a result of pregnancy. This is the "economic cost" of childbearing in economic terms. For today's Chinese women, this represents a considerable cost.

Why is the Birth Rate Declining?

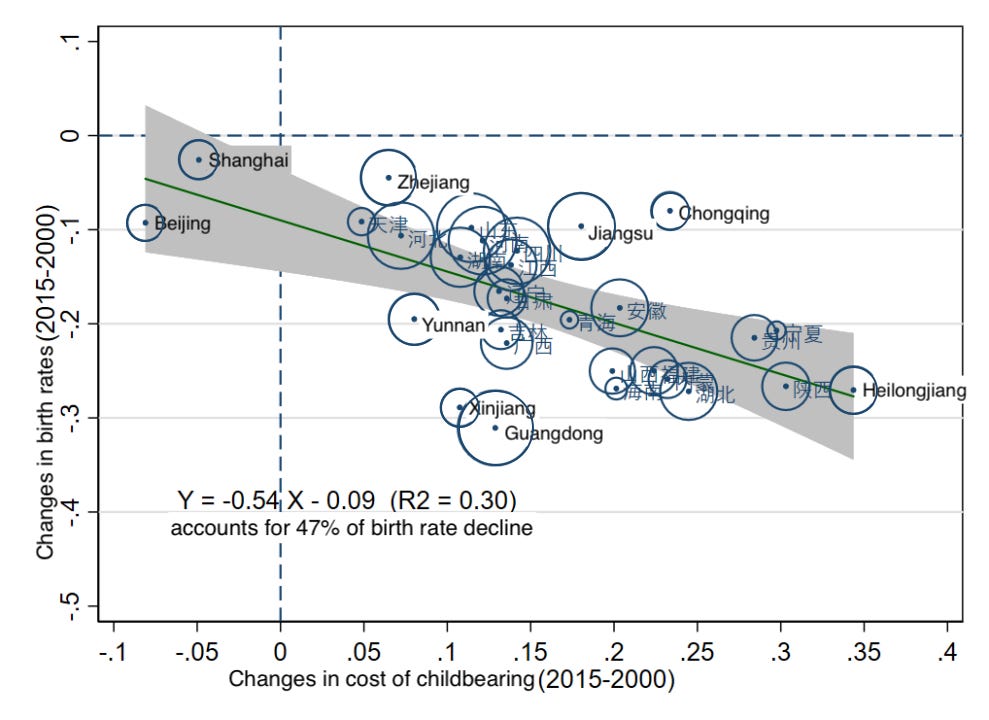

Figure 3 shows the changes in childbearing costs and birth rates across different regions [represented by dots within circles] in China. It is necessary to note that this graph only presents a simple correlation analysis, and the patterns shown should not be interpreted as causal relationships. The horizontal axis represents the changes in the cost of childbearing, while the vertical axis represents the annual changes in the birth rate. It is observable that from 2000 to 2015, in places where the childbearing costs, especially the opportunity cost of childbearing, rose more rapidly, the decline in the birth rate was sharper. This may partially explain the rapid decline in birth rates in recent years. The high opportunity cost of childbearing might be a primary reason.

The Dynamic Changes in Wage Income

Opportunity costs certainly encompass more than just employment. Figure 4 displays the impact of childbearing on the income of men and women. It is clear that men's salaries largely remain unchanged. Women's salaries, however, show a noticeable decrease. Over time, this decline in women's income continues, never returning to the level prior to childbirth. The data used in Figure 4 is somewhat outdated, but it is believed that this trend would still remain even with updated data.

The Dynamic Changes in Household Income, Consumption, and Savings Rates

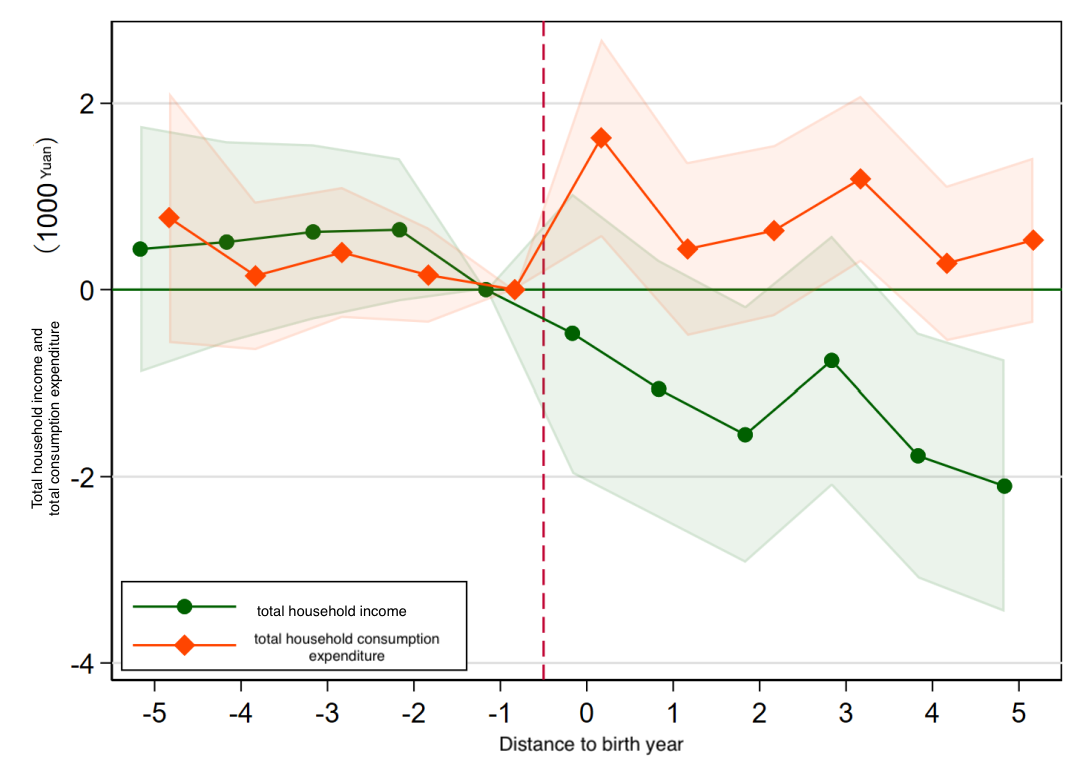

To have children, some individuals must forgo work. Without employment, there is no income, which naturally leads to a decrease in household income. Meanwhile, the total consumption of a family might increase after the birth of a child due to the added expenses of child-rearing. Figure 5 illustrates the changes in total household income and consumption before and after childbirth. It is evident that before having babies, total income and total consumption are essentially balanced, but after childbirth, these two indicators start to diverge, with consumption rising and income falling. This implies that the household savings rate also sees a significant decrease. Overall, it is difficult for families to increase their savings in the years following the birth of a child.

There has been a debate over the economic attributes of children among some economists. Some argue that children are "consumer goods," as altruistic parents derive utility from raising and accompanying their children. Others consider children to be "investment goods," suggesting that the time and money spent on children are expected to yield long-term benefits, such as providing support in old age. Then, what is the intrinsic nature of children? This is a discussion-worthy question. Numerous laws of economics have provided an answer: according to Gary Becker's theoretical framework, children can both provide utility and offer future security. Therefore, children possess a combination of attributes.

Figure 6 displays the changes in household savings before and after having children. It can be seen that after having children, the savings rate declines, which lends some credence to the notion that raising children will provide support in old age.

Dynamic changes in consumption

Figure 7 shows the categorization of the dynamic increase in consumption. It is evident that within one year before and after childbirth, the increase in consumption is mainly concentrated on food, clothing, medical care, and residential facilities, among others, while the consumption in education, culture, transportation, and communications decreases. As the child grows older, food consumption gradually declines, and spending on residential facilities and medical care gradually returns to previous levels; educational and cultural consumption begins to rise, which may be due to the increase in costs of childcare services such as nurseries. It needs to be explained that Figure 7 only shows the consumption changes of families with children under the age of five. Consumption after kids enter primary school is not included.

After the child reaches the age of two or three, family consumption in childcare and education noticeably increases. Even though consumption in other categories may decline, the overall level of consumption continues to rise. The consistent decline in transportation and communication expenses is noteworthy. This trend may be attributed to the central focus on young children within a family, which often limits opportunities for travel and outdoor activities such as hiking. Various other forms of consumption may also become less practical after a child is born.

Overall, for a family, the birth of a child marks a pivotal transition, impacting various facets including mindset, consumption patterns, and income. Deciding to have a child often requires great courage, and this courage is reflected in numerous small transitions.

Today's session has been focused on the cost of having children. As a matter of fact, the expenses associated with raising children often reflect the depth of parents' love for their children, and I believe all parents have a profound understanding of this.

How to reduce the cost of childbearing

Reducing the cost of childbearing can encourage more births, which I believe requires collaborative efforts between the government, businesses, and society.

Family members should love and support each other, work together, and face the new changes brought by the birth of a child.

Companies should be willing to hire female employees and not discriminate against them because they might give birth, take maternity leave, or raise children in the future.

Government policies and systems should also practically help women better achieve employment. The cost of childbearing is not just the direct cost of raising children but also includes the opportunity cost resulting from the decline in females' labor participation. How to reduce these costs and create a just employment environment for women is also an important task on the agenda of reducing the cost of childbearing.

At the same time, people must recognize that the cost of childbearing can differ greatly in different regions. The research presented above is merely a statistical reference. Family circumstances can vary widely and may not always align with the situations analyzed in this research. In some cases, there may even be significant deviations. In the future, more data and analytical methods are needed to reach more comprehensive conclusions. This research only discusses the aspects of labor supply and family expenditure; there are many other areas, such as mental and physical health, that require further analysis.

I hope to see the establishment of a truly gender-equal society that is friendly to both men and women. In terms of childbearing, both mothers and fathers face hardships. The public needs a strong social support system that provides everyone with equal educational and labor opportunities and a fair working environment. This is very important for each person and also very important for the transformation of society's birth rate trends and future development.

Oh yeah having just had a baby, my career is completely on the back burner. My little boy needs so much attention and love and there’s no point schlepping him off to a daycare right now, in part because I don’t make enough to justify it. It’s become a “luxury” service.

It would be worthwhile to examine the childcare contributions made by family members, both informally (occasional weekends, help on sick days) and routine (daily care while the mother goes to work). The Chinese family structure has been changed drastically over the past decades by the one-child policy, and this may have practical consequences. Mobility is another factor: in the US, it is fairly common for new parents and grandparents to consider moving (and changing jobs) to be nearer one another, both so grandparents can enjoy the children but also so they can be of help.